A young daughter imprisoned in place of her father struggles after prison torture, gang rape

Police stormed Salaam’s grandfather’s home in southern Syria, looking for […]

22 February 2017

Police stormed Salaam’s grandfather’s home in southern Syria, looking for the 12-year-old girl’s father. At that time, October 2012, security forces were arbitrarily raiding homes and arresting men in Daraa. Unable to find him, they arrested Salaam instead.

Salaam spent 45 days in a Daraa prison. When she was released, after her father turned himself in, her mother says she was shocked by what she found.

The girl’s body was covered with bruises, and she couldn’t move her shoulder, Umm Salaam tells Syria Direct’s Yasmine Ali. “Her face was disfigured—the bones in her lower jaw were shattered.”

While detained, Salaam says she was raped by 11 men and beaten.

After her release, “she wouldn’t speak to anyone,” says Umm Salaam.

Salaam is one of at least 1,400 children detained by Syrian authorities since 2011, according to a 2016 Human Rights Watch report.

“Security forces targeted specific activists for arrest, and if they were not at home, arrested family members, including children, instead,” the report stated.

More than four years later, Salaam lives in Jordan with her mother and sees a counselor, Lujain Ghalwanji, who says she has worked with numerous other children like Salaam. Ali spoke with Ghalwanji with the permission of Umm Salaam.

“You have to treat a child who has been traumatized by war like she is completely normal, no different from any other kid,” says Ghalwanji.

“She has to know that you’re treating her because you genuinely care for her well-being, not because it’s your job.”

Umm Salaam, 36, Salaam’s mother:

Q: What happened the night Salaam was detained?

One night in October 2012, around 3am, security forces stormed my family’s house, searching for my husband. Salaam and I had been staying with my father.

I told the officers that I had no idea where he was. They responded by taking my daughter as a hostage until her father turned himself in.

I tried reasoning with them. I told them that she was an innocent child, that she hadn’t done anything. Many people tried to intervene, but every attempt failed.

Q: How long was Salaam detained? What happened to her?

Salaam was taken to the 52nd Brigade in Daraa for 45 days, until her father turned himself in. During that time she was beaten, tortured and insulted. She still has clear marks on her body from the beatings and torture.

She was gang-raped by 11 men.

[Ed.: Umm Salaam says that her husband, who turned himself in to authorities 45 days later, died in prison. She says that security officials informed her of her husband’s death.]Q: Describe Salaam’s physical and mental state once she was released from prison.

She was in horrible condition. She didn’t even recognize me at first. Her body was covered with bruises and she couldn’t move her shoulder. Her face was disfigured—the bones in her lower jaw were shattered. She was constantly afraid and wouldn’t speak to anyone.

Q: Did you take her to the hospital for treatment?

As soon as Salaam was released, I took her to Damascus for vaginal reconstruction surgery since she was repeatedly raped.

We left for Jordan a few months later, on January 15, 2013. She began going to physical therapy for her shoulder.

Q: Did Salaam respond well to physical therapy?

At first, she refused to go because she was afraid to leave the house. She didn’t trust anyone. I sought help from many doctors and counselors before I was finally able to convince her to go.

Her shoulder hasn’t fully recovered; she’s still seeing a physical therapist.

And she still needs reconstructive surgery for her jaw, since she can’t chew her food. But surgery costs JD30,000 ($42,000).

Q: How is Salaam doing now?

She’s doing well, a lot better than before. But her face is still disfigured, which has affected her self-esteem. She’s afraid of ambulances and police stations. She was terrified when we went to the police station in Jordan to get a housing identification card.

But after more than four years, Salaam still hasn’t told me about everything that happened to her in the prison. I wish that she would in order to soothe the pain in both of our hearts.

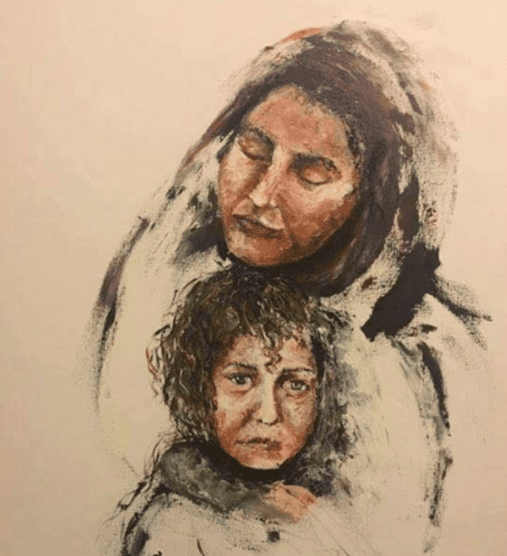

When I look into my daughter’s eyes, I get the sense that she’s older than I am.

**

Lujain Ghalwanji, a program coordinator and counselor at Zakat Foundation of America in Jordan. Ghalwanji, who is currently getting her masters in Social Work at the University of Jordan, has been Salaam’s counselor since 2015. She spoke with Syria Direct’s Yasmine Ali with the permission of Umm Salaam.

Q: When you first met Salaam, how was she coping with the trauma she had experienced?

Salaam has suffered a lot. She was exposed to many things at an early age.

As a result, she lost complete trust in everybody, especially men. She also had low self-esteem.

She was very introverted and isolated herself from others. She refused to leave the house and didn’t want to go to physical therapy.

Q: As her counselor, how has Salaam’s behavior changed through your sessions? Has she started to open up to you and trust others?

Of course it was hard to work with her at first—she didn’t trust anyone, and I was no different.

Salaam wouldn’t speak to me at first. After many visits, I was able to get her to open up. I grew close with her. I considered her a friend. I told her about my studies and work. Even if she didn’t respond, I kept talking. I described school and how she’d be able to become an important person. I portrayed the reality that she wanted to see.

Most importantly, I treated her like a completely normal child, one who hadn’t been through what she had experienced.

Q: How would you describe Salaam’s current psychological state?

She’s doing much better than before. But she still suffers physically—she needs reconstructive jaw surgery.

Q: How do you help children recover from traumatic experiences?

You have to treat a child who has been traumatized by war like she is completely normal, no different from any other kid. You have to help her develop self-confidence; you have to establish trust.

She has to know that you’re treating her because you genuinely care for her well-being, not because it’s your job.

At the end of the day, these children are the hope for Syria’s future.