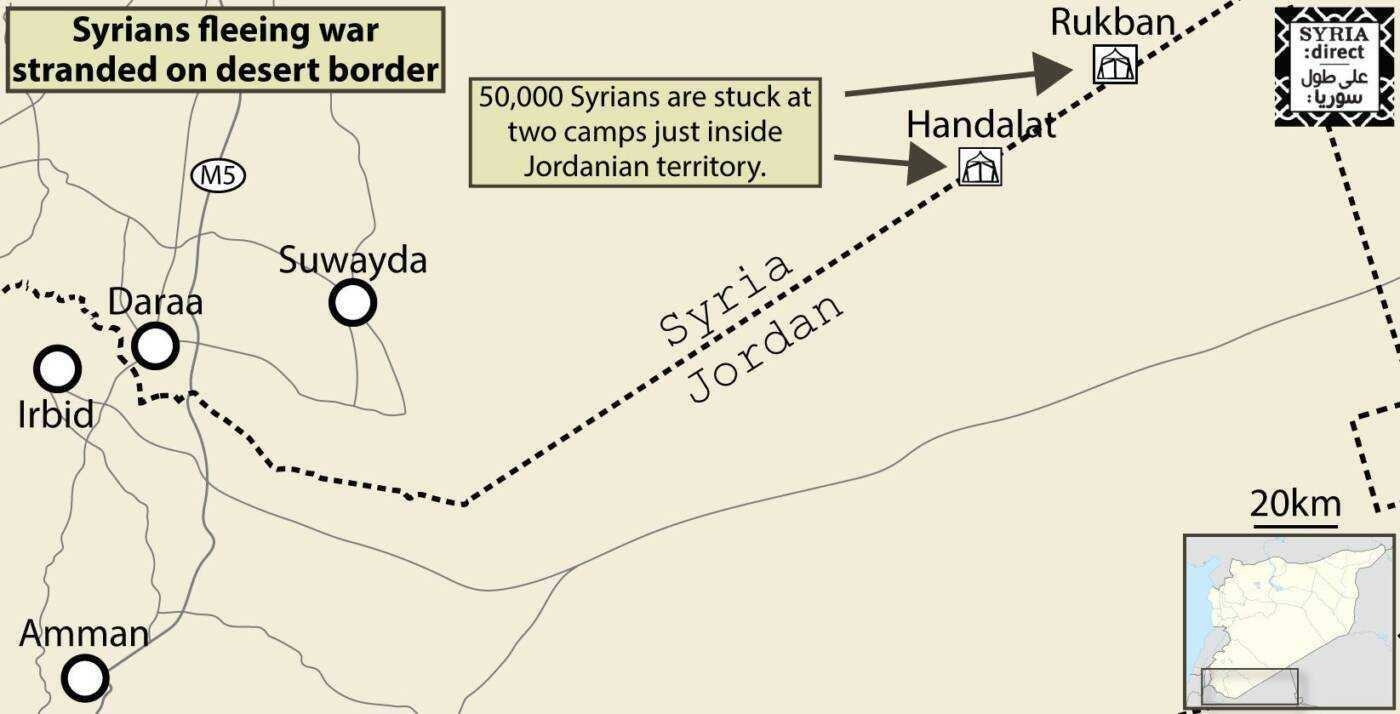

50,000 displaced Syrians stranded at Jordan desert border

AMMAN: When Islamic State fighters captured his east Homs village […]

21 April 2016

AMMAN: When Islamic State fighters captured his east Homs village last May, Mohamed Homsi didn’t hesitate to pack his wife and seven children into the back of a pickup truck and head south.

“Most people fled to Damascus, but my sons were wanted by the regime for avoiding military service so I headed for Jordan,” Homsi, who used a pseudonym and requested that his home village not be named for this story, told Syria Direct.

The family spent the night in the back of the pickup, riding across the eastern Syrian desert towards an informal border crossing with Jordan named Rukban, 250km northeast of the capital of Amman.

“When we got to the Jordanian-Syrian border, the truck couldn’t go any further” because Jordanian border guards were not allowing vehicles to pass, said Homsi.

“We got out and walked for about an hour to a place where there was a large wall made of sandbags,” said Homsi, “There were already thousands of people there.”

Over the past 11 months, Homsi and his family have lived at this desert encampment on the Jordanian border known to aid workers as “the berm,” after the sandbag wall that demarcates the settlement’s southern border.

Citing fears that Islamic State partisans were among the displaced, the “Jordanian military started preventing many Syrians from entering through the eastern border crossings” at Rukban and Hadalat, located 50km to the west, in March 2015, Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported.

From this point, the number of displaced Syrians migrating toward the berm steadily grew, with the Jordanian government admitting only a few dozen people from Rukban and Hadalat per day, according to another HRW report from December 2015.

Satellite imagery captured by HRW shows that the number of tent structures at the Rukban settlement increased from 68 in April 2015 to 1,450 in December of that same year.

In recent weeks, the Jordanian government began admitting significantly more displaced Syrians from the two settlements per day, allowing as many as 300 people to enter the country seven days a week, Amman-based al-Ghad reported on Thursday.

Nevertheless, an estimated “50,000 people” are still living at Rukban and Hadalat, Jordanian government spokesman Mohamad Momani told reporters on Sunday.

Those displaced Syrians who spoke to Syria Direct from inside the berm describe conditions there as “inhumane.”

“There are no bathrooms. Bugs and insects are everywhere and water is delivered sporadically,” Abu Anas, another camp resident, told Syria Direct via the messaging application WhatsApp on Wednesday.

Abu Anas, originally from the eastern Homs countryside, has lived at Rukban for over a year. “I can’t go back to live under IS and the regime will arrest me if I went to their territory,” he said.

Last November, Abu Anas’s wife gave birth inside the camp.

“Many women who have no experience with medicine are helping deliver babies in the berm,” said Abu Anas.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is responsible for providing basic health care services to those living at Rukban and Hadalat, while the World Food Programme (WFP) is responsible for food deliveries and UNICEF delivers water via truck, an official with the ICRC told Syria Direct.

During the first three months of 2016, ICRC managed the distribution of “1.1 million ready-to-eat meals, trucked 25,500 cubic meters of drinking water and provided 18,000 medical consultations to the people stranded in Rukban and Hadalat,” ICRC spokeswoman Hala Shamlawi told Syria Direct on Wednesday.

“Many of them come with nothing but their clothes on,” Shamlawi said, referring to the displaced Syrians arriving from across the desert.

Camp residents said aid workers have limited access to the camps and that the entrance of food, water and medicine is often sporadic.

“Some days, when the weather is bad, the aid doesn’t come,” said Homsi.

“On those days we don’t know what to do with ourselves,” he adds.

Camp residents such as Homsi are waiting their turn to enter Jordan and register with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) so that they can eventually seek asylum in a third country.

But Jordanian authorities say they cannot process arrivals any faster given security risks.

“We know that inside that camp are Daesh elements; and so they are going through a very strong vetting system,” Jordanian monarch King Abdullah told the BBC this past February, referring to the Islamic State.

In the same interview, Abdullah noted that his country is hosting more than 637,000 UNHCR-registered Syrian refugees, while the governments reportedly pressuring Jordan to admit the displaced at the berm are squabbling over the admission of a few thousand Syrian refugees into their respective countries.

“If you are going to take the higher moral ground on this issue, we’ll get them all to an airbase and we’re more than happy to relocate them to your country,” the king told the BBC.

Meanwhile, displaced Syrians at the berm are preparing to spend yet another summer in the Jordanian desert, where temperatures regularly reach more than 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 degrees Celsius).

“We don’t know what will happen to us this summer,” said Abu Anas, adding that previous summers had claimed the lives of the elderly and sick.

“There is a burial ground in the berm with more than 60 graves,” he said.

“I buried some of them myself.”