A medical ‘disaster’ in East Ghouta as chronic illnesses go untreated

AMMAN: On the floor of his home’s courtyard, Mohannad goes […]

6 December 2017

AMMAN: On the floor of his home’s courtyard, Mohannad goes through the daily routine of dressing his daughter Rawan.

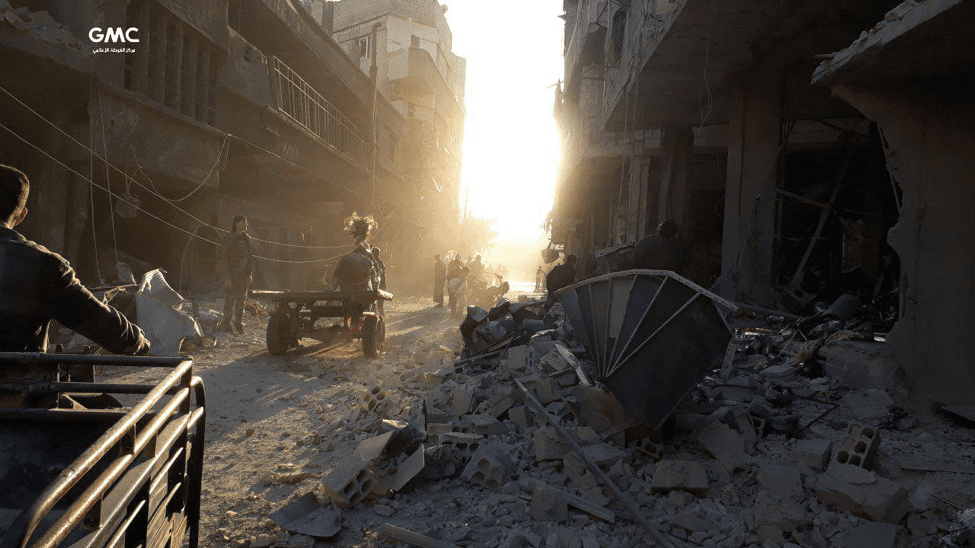

Tattered blankets cover the windows of Mohannad’s modest, concrete house, located in a bombed-out, rebel-held northeastern suburb of Damascus. Overhead, sweaters and bedsheets dry on a rope stretched from one end of the courtyard to the other.

Beneath them, seven-year-old Rawan lies still on a brown mat. Her father slips a pair of cheetah-print pajama pants over a diaper far too large for her thin frame. Mohannad moves with quick precision—he’s done this many times. Rawan, who has cerebral palsy, cannot move her legs, and her arms are stuck in place, bent at the elbows. Mohannad works a sequined green sweatshirt over her arms, and covers her ribs.

Rawan was born with the neurological disorder, which, though not immediately life threatening, impairs her muscle control and fine motor skills. With no wheelchair, she cannot move around the courtyard to play with her brothers, and relies on her parents to help her sit up, eat and dress. For many people with Rawan’s symptoms, treatment includes physical therapy and medications to manage seizures and involuntary muscle movements.

Years ago, when Rawan was a toddler, she took medicine to cope with muscle pain and regularly visited doctors in Damascus for treatment, says Mohannad.

But today, Rawan, her parents and four brothers live under siege, cut off from the Syrian capital and unable to reach hospitals that can provide treatment. The family lives in Hamouriyah, a town within the opposition-held East Ghouta enclave encircled by government forces since 2013.

For Rawan, the siege is life-threatening. In addition to her cerebral palsy, doctors told her parents last month that she now suffers from kidney failure due to a lack of nutrient-rich food. In the besieged pocket, the high price of most basic goods—including soft foods that are safe for Rawan—is too expensive for Mohannad. Instead, Rawan drinks only milk, he says.

In East Ghouta, the medical care that Rawan and thousands of other residents suffering from chronic conditions need is unavailable due to prolonged, acute shortages of medical supplies. Across the opposition enclave, hospitals and pharmacies are out of drugs for thousands of residents with cerebral palsy, kidney failure, cancer and other illnesses, six East Ghouta doctors tell Syria Direct.

“I’m not exaggerating when I say that medicine for chronic illnesses is totally gone,” says Alaa, the director of a hospital in the East Ghouta town of Jisreen. In the past month, at least three of his patients died as “a result of a lack of the necessary medicine.” He expects the number of deaths to increase.

Meanwhile, daily shelling and airstrikes by Syrian government forces strain supplies of the most basic emergency medicine and equipment needed to treat injuries. Stocks of blood, IV pouches and gloves are “rapidly” running out in the 21 medical facilities Doctors Without Borders (MSF) supports across East Ghouta, according to a report the organization published in late November. The ongoing siege makes replenishing the dwindling supplies next to impossible.

East Ghouta’s medical shortage is nothing short of a “disaster,” the MSF report concluded.

While Rawan’s family has gone to various doctors in East Ghouta for help, hope of treatment for her cerebral palsy—let alone kidney dialysis treatment to save her life—is slim. Ghouta’s only dialysis center closed down in February after its last remaining supplies ran out. The center is likely to remain closed, as doctors have no way to source more supplies.

Elsewhere within the encircled pocket, supplies for dialysis treatment are simply “not available,” says Sami a-Shami, a doctor who helped found East Ghouta’s Pharmacists’ League in 2015.

The Pharmacists’ League monitors pharmacies across East Ghouta and takes stock of available medicine within the roughly 100-square-kilometer enclave. Last month, the League conducted a study of exactly how much medicine is missing from East Ghouta’s shelves.

Their findings: the “absence and the near absence” of many groups of life-saving drugs, says a-Shami.

“Every day we lose another drug.”

Total encirclement

Syrian government forces first encircled East Ghouta in 2013, transforming it into an island of rebel control cut off from the capital city.

During years of siege, a network of underground smuggling tunnels and one overland trade crossing in East Ghouta’s north sustained the enclave with supplies of food and medicine.

When open, the tunnels allowed supplies of flour, grains and even vaccines for livestock through to the dozens of modest agrarian towns and villages that dot the encircled enclave.

But earlier this year, Syrian regime forces captured three opposition-held eastern Damascus suburbs where the smuggling tunnels originated, and closed them. The tunnel trade was over.

Then, in early October, regime forces reportedly closed the last crossing into the opposition-held suburbs. Located outside of Douma, a city in East Ghouta’s northernmost corner that is widely considered the enclave’s de facto capital, the al-Wafideen crossing was a vital entrypoint for food and other supplies—especially after the tunnels were shut down.

Two months later, al-Wafideen remains largely closed, with only small, sporadic shipments of cheap smuggled grain and supplies for yogurt production getting through.

Two UN aid convoys entered East Ghouta over the past month, but reportedly did not contain enough food or medical supplies to reach all of the enclave’s estimated 400,000 residents.

The most recent UN convoy entered in late November, delivering medicine and emergency medical supplies. But no drugs or equipment to perform surgeries or treat chronic illness were included. In October, 41 trucks carrying World Food Programme (WFP) food entered with enough supplies to feed an estimated 10 percent of East Ghouta’s population for a period of one month.

The October shipment was only the sixth that the WFP was able to carry out so far in 2017, the agency said. In all, 110,000 East Ghoutans received the aid since the start of the year.

With medicine for chronic, life-threatening diseases all but absent from the most recent aid shipments into East Ghouta, medical officials there describe a dire situation. At one hospital in Hamouriyah, where Rawan and her family live, doctors have not received new drugs to treat chronic illnesses in “more than a year,” hospital spokesman Abd al-Moayyen tells Syria Direct.

Without antibiotics, anaesthesia or chemotherapy drugs, doctors at Abd al-Moayyen’s hospital can only treat emergency injuries. A number of cancer patients at the hospital have died in recent months as a result, the spokesman said.

Expired medicine

As stocks of viable medicine run out, doctors across Ghouta tell Syria Direct that they are administering medications long past their expiration date to patients with chronic illnesses.

Doctors at Abd al-Moayyen’s Hamouriyeh hospital are providing expired medicine that is “undamaged, but less effective” to patients, the director said.

Medical facilities across East Ghouta have done the same “once all other supplies were exhausted,” says Hussam, a member of the East Ghouta United Medical Office overseeing hospitals throughout the besieged enclave.

The impact is nothing short of devastating. Among patients of other diseases, at least 550 people with diabetes across East Ghouta are in need of insulin medication, and 45 others—including Rawan in Hamouriyah—are suffering “various stages” of kidney failure, according to a report released by the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) in September.

But insulin clinics face major shortages of the required medication, and dialysis treatment simply no longer exists in East Ghouta, doctors tell Syria Direct from within the enclave.

In Douma, one father, Abu Ahmad tells Syria Direct he worries for his 14-year-old son with hemophilia, a blood disorder that impairs his ability to form blood clots and stop bleeding when injured. Factor VIII, a medicine that helps treat hemophilia, is nonexistent in Ghouta, says Dr. Abu al-Yasser, who works in Douma.

Without the medicine, Abu Ahmad’s teenage son lives in fear of even the smallest cuts and scrapes.

“My son lives confined to our house,” says Abu Ahmad. “He doesn’t go to school, or spend time outside due to a fear that he could be injured.’

“Even a small cut could lead to major bleeding and death, especially with the severe bombings we’re experiencing on a daily basis here.”

By Dr. Abu al-Yasser’s estimate, Abu Ahmad’s son and other patients with hemophilia have not taken factor VIII medication in two years.

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly how many East Ghoutans like Abu Ahmad’s son and Rawan are suffering from chronic, life-threatening conditions, says Hamouriyah hospital spokesman Abd al-Moayyen.

“But what we can say, is that the lives of everyone suffering from a chronic disease are in danger,” he said.

‘Everyone is waiting’

In Hamouriyah, Mohannad knows that if nothing changes, his daughter Rawan does not have much time.

Rawan has lost a dangerous amount of weight in recent months. Today, her body is frail and emaciated. Doctors cannot give her the dialysis treatment she needs to save her life. Nothing is stopping her kidneys from completely shutting down and killing her.

An estimated 500 men, women and children in East Ghouta with “complex medical cases” are in dire need of medical evacuations from the besieged pocket, UN Under-Secretary for Humanitarian Affairs Mark Lowcock said in a statement late last month to the UN Security Council.

In Jisreen, hospital director Alaa tells Syria Direct that a handful of his patients are suffering complicated illnesses he can’t even diagnose, unless they visit more specialized, well-equipped hospitals outside of East Ghouta.

But under a tight government siege, Alaa’s patients “are stuck here in East Ghouta,” the doctor says, “not even knowing the cause of their pain.”

Mohannad knows that Rawan’s chances of survival depend on her getting out of East Ghouta. He shared Rawan’s story with local activists in recent days and agreed to share photos of her online in an effort to “get my daughter out of Ghouta for treatment.”

Medical evacuations are rare, but they do occasionally happen. In September, Red Crescent workers reportedly transferred an infant from Harasta with a congenital heart defect to Damascus for treatment. In August 2016, two conjoined infants were evacuated to Beirut for surgery.

While Rawan’s parents hope for an evacuation, they continue to take care of her as best they can under the siege.

Rawan’s case is hardly unique, says hospital spokesman Abd al-Moayyen. “After the loss of medicine, everyone is waiting now,” he tells Syria Direct.

“They are waiting for the siege to be broken, waiting for the medicine to return, waiting for their lives to go on.”

With additional reporting by Alaa Nassar, Faten Zoubi and Kafa al-Faisal.