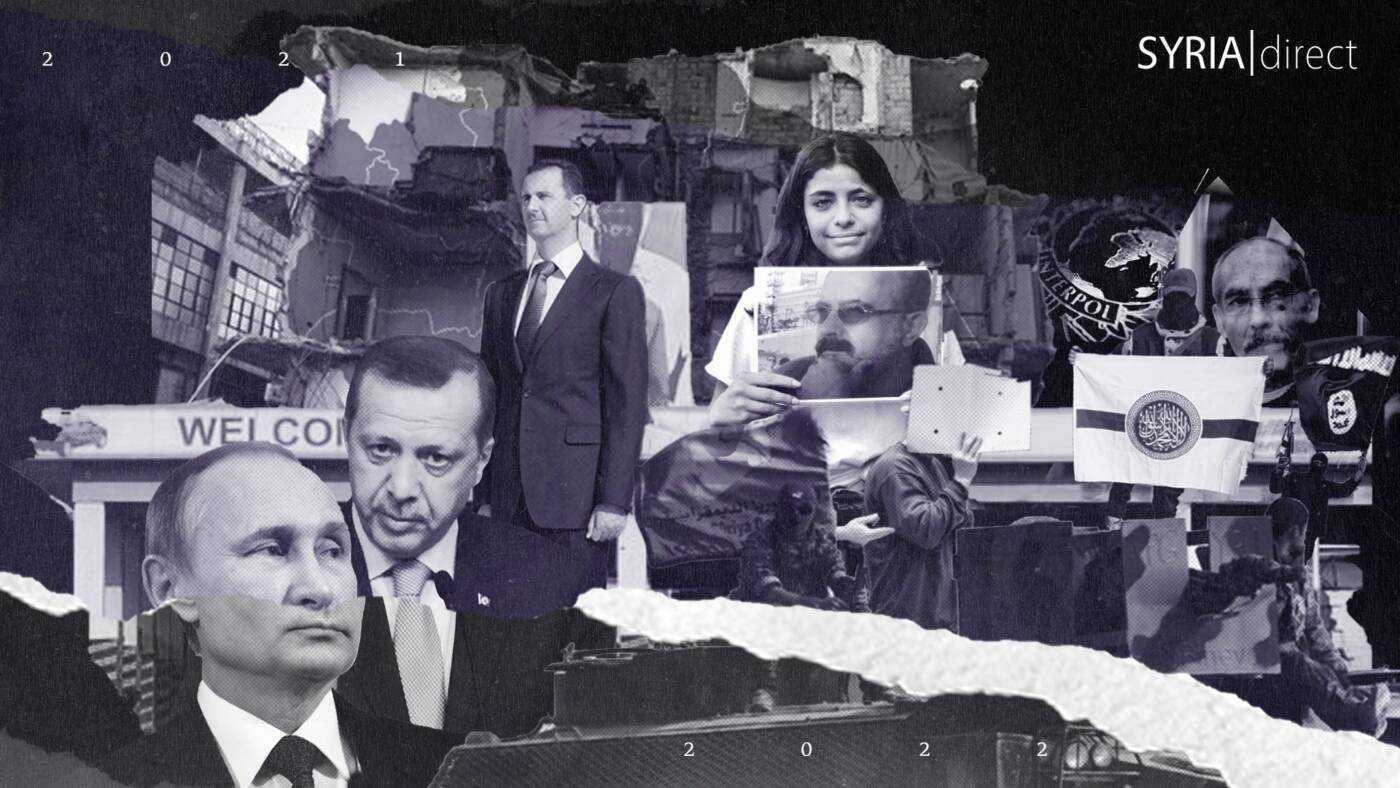

A sketch of Syria’s 2021 and what to expect in 2022

In the year marking a decade of the Syrian uprising-turned-conflict, regional normalization efforts with Damascus gained steam while the two stalemates in the northeast and the northwest seem to have settled in a fragile stability.

27 December 2021

BEIRUT – In the year marking a decade of the Syrian uprising-turned-conflict, regional normalization efforts with Damascus gained steam while an economic downward spiral pushed 90% of Syrians into poverty. At the same time, with Bashar Al-Assad controlling around 70% of the country’s territory, the two stalemates in the northeast and the northwest seem to have settled in a fragile stability.

The northeast

In 2021, the Turkish president’s threatening rhetoric over a possible intervention in northeast Syria, controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), has been as constant as the breaches of the ceasefire. “With these tit for tat attacks, things can go wrong,” but Turkey is aware that there is no “military solution” in the northeast, Heiko Wimmen, Project Director of Syria at International Crisis Group, explained. “I wouldn’t expect that Turkey would like to expand the zone it occupies in the northeast. A move like this will require a difficult conversation with the Russians,” he added.

“Russia has drawn a red line that any further Turkish intervention is not going to be accepted, and for Turkey to do something, it does need a Russian green light,” according to Charles Lister, Director of the Syria program at the Middle East Institute in Washington, D.C. Due to shared regional interests – like the [gas pipeline] Turkstream project and the S-400 missile system – Moscow and Ankara are “constantly balancing against each other in Syria, and from both of their perspectives, that dynamic is far more important to sustain than the relationship deteriorating,” Lister added.

Another complicated dance is the one of the SDF. Their “most preferred partner” is the US, and the Biden Administration has insisted they will not withdraw their troops from the northeast, Lister explained. Despite their preference, the SDF has kept open the door to Moscow and Damascus, even as “the deal that Russia has put on the table is a surrender of everything that the SDF has gained over the past six years,” Lister noted. “Damascus is not ready to give them [Kurdish authorities] anything in terms of autonomy,” Wimmen said.

In 2022, Lister expects the SDF to encourage the US to push for a political settlement with the regime for progress on the UNSC 2254 resolution. “This is a recognition that the SDF thinks that the conflict at large has come to a frozen point, and now is the time to push for diplomacy,” he said. Wimmen forecasted that “the status quo will prevail” for now, but in the long run, the Kurdish position could be seen as precarious. “It is plausible to think that Damascus will wait it out and one day the Americans will go; it may take five or ten years, but Damascus will still be here – it’s a waiting game,” he concluded.

The northwest

Despite constant breaches during 2021, the ceasefire appears to be holding in the northwest, controlled by the opposition forces and the Islamist fundamentalist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (THS). “Even though the ceasefire is being violated on an almost daily basis, that situation suits almost everybody far better than any of the other alternatives. This messy status quo is most likely to continue,” Lister said.

The alternative – a full-fledged attack by Damascus on the area – seems unlikely. “Turkey has continuously expanded its presence. The likelihood that this would lead to a direct confrontation between Turkish and Syrian troops is quite high, and the Russians are not interested in that,” Wimmen said.

A massive attack would translate into thousands of people seeking safety in Turkish territory. A “clearly marked red line” for Ankara is “the northwest remaining stable, i.e., no threat of refugees crossing the border,” Lister said.

An operation by Damascus could also lead the jihadi fighters currently in the northwest, many of whom come from former Soviet Union countries, to spread, creating a nightmare scenario for Russia. “As long as you have these [jihadist] guys boxed in Idlib, they are not going to give you trouble otherwise,” Wimmen explained.

HTS, the group in control of Idlib, has “consistently tightened the screws on other groups that may carry out attacks on their own account. HTS seems not to be interested in any kind of escalation,” Wimmen said. Also, HTS’s “willingness to consider opening unofficial trade crossings with the regime” indicates “HTS’ interest to consolidate the existing status quo to deter any military escalation,” Lister explained.

HTS, a designated terrorist group by the UNSC, has been trying to ‘rebrand’ itself after severing ties with ISIS and Al Qaeda years ago. However, Lister doesn’t expect any move to delist HTS. Still, there is a “discussion in the US about restarting a limited amount of stabilization assistance in the northwest, in areas where they are not seeing HTS interference, intimidation or infiltration,” he added.

The Daesh file

In 2021, 267 Daesh attacks in northern Syria caused 183 fatalities, marking a decline from the 572 attacks and 299 deaths in 2020, per Rojava Information Center figures.

Despite this trend, Lister expressed concern about “the likelihood that ISIS has used the last twelve months in Syria to quietly reconstruct its finance and logistical networks” to a stage where “they are able to conduct more sophisticated attacks.”

Since ISIS’s territorial defeat in Baghouz in 2019, around 10,000 suspected ISIS members linger in prisons in eastern Syria. “The SDF internal judicial mechanisms are increasingly well looked upon by counter-ISIS coalition members,” pointed Lister. Still, he does not foresee “any real progress” for the fate of these inmates in 2022.

The futures of the 60,000 ISIS member families in northeast Syria’s al-Hol camp have been thrown into limbo amidst an ISIS resurgence in the camp that resulted in more than 95 killings in 2021. “We passed the point of no return. The insecurities in al-Hol camp are unprecedented; the situation continues to get worse in terms of humanitarian conditions, and no amount of aid alone is going to resolve this, ” Sara Kayyali, a Syria researcher at Human Rights Watch, said.

In 2021 the repatriation of children and women gained some traction. However, Kayyali urged for these “ad hoc piecemeal returns” to evolve into a “comprehensive plan” to repatriate and try these people. “Repatriating really needs to happen at a much larger scale, and quicker, but I am not very optimistic,” Basma Alloush, a nonresident fellow at the Washington-based Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP), said.

Lister pointed to “solid speculation” that this year “the SDF has started to drag its feet, put additional bureaucratic barriers in the way of governments who openly want to bring their citizens back” because if large numbers of westerners are repatriated, “the reasons for continued western investment in the northeast will start to decline” and they will “lose political leverage.”

The death of the cross-border mechanism?

With 60% of the population of Syria being food insecure and 13.4 million in need of humanitarian assistance, aid delivery is beyond critical now. Last July, the use of the Bab al-Hawa crossing (in the northwest) to deliver aid to Syria was renewed for six months. Although the related UNSC resolution is expected to be renewed in January 2022, the prospects appear dim for July 2022’s voting.

“Russia will try to discredit the mechanism if not veto it all together,” Alloush predicted. “It is going to be increasingly difficult to maintain Bab al-Hawa, as the Syrian government, UN agencies and ICRC are moving actively towards cross-line,” Kayyali explained. The alternative cross-line method seems tricky given Damascus’ record of diverting aid and weaponizing it against non-government-held areas.

“If there’s any disruption on the cross-border mechanism, the lives of over three million people will be at risk,” Alloush said. “If cross-border aid is shut, HTS would be wholly dependent on cross-line, and that’s the trigger that could catalyze a notorious escalation,” Lister warned.

The push for normalization

Normalization efforts with the Assad regime intensified in 2021: Jordan fully reopened the Jaber border crossing and resumed flights to Damascus; the UAE’s Foreign Minister visited Damascus to discuss commercial partnerships; and Interpol – whose president is now an Emirati general – reintegrated Syria back into its information exchange network.

Kayyali warned that Syria “will be able to use the Interpol’s system to put out arrest warrants that are politically motivated” and “abuse” the red notice system as countries like China have done before. “States need to take whatever request given by Syria with a grain of salt because people’s lives could be at risk,” Nessma Bashi, a Legal Fellow at Syria Justice and Accountability Center (SJAC), said.

Eyes are on the Arab League’s summit in Algeria in March 2022 for a possible return of Damascus. Wimmen felt skeptical about the idea that Arab powers “playing nice with Damascus to get them out of the Iranian embrace” would work given that “the Syrian regime owes them [the Iranians] their survival.”

Lowering the ‘hype’ on normalization efforts, economic analyst Karam Shaar said that “UAE and Jordan are trying to normalize relations but not at any cost; they would like to see serious steps on the side of Al-Assad, and I don’t think he will give them any meaningful concession.”

The ‘reconstruction’

In September 2021, the Syrian Minister of Industry made a call for investors to rehabilitate destroyed factories. This call “highlights the depth of despair of the government” and points to the trend of “privatizing the public sector” in a similar fashion to the Yeltsin era in Russia, where “oligarchs gobbled everything for low prices; this is already happening in Syria,” Shaar explained.

Kayyali dismissed the call as a “publicity stunt” but added that to understand “how reconstruction happens in Syria,” one should watch how the UAE agreement to build a power station unfolds in 2022.

Wimmen doubted any investors would be willing to invest “the enormous amount of money that it would need to rebuild Syria’s infrastructure” and risk being affected by the US Caesar Sanctions.

Unsafe returns

In 2021, Denmark, deeming Damascus and its countryside safe for return, revoked dozens of residency permits of Syrian refugees. This move counters the Commission of Enquiry findings of torture in detention, custodial deaths and enforced disappearances in 2021. This year, the Syrian Network for Human Rights documented 1,116 extrajudicial killings of civilians and 1,748 arbitrary arrests, and Human Rights Watch documented cases of arbitrary detention, torture and extrajudicial killings among Syrian refugees returned from Lebanon and Jordan.

Besides safety concerns, another practical obstacle for return are the violations of Housing, Land and Property rights. Since 2011, there have been “dozens of laws and decrees issued by the regime that make dispossessing very easy, particularly for individuals that are seen as opposition,” Reem Salahi, a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council, said.

The accountability path

In 2021, the Koblenz Trial delivered the first verdict against the Syrian regime’s crimes against humanity. Former Syrian secret service agent Eyad A. was sentenced to four and a half years in prison. The other defendant, Anwar R., is accused of supervising the torture of 4,000 prisoners, and his verdict is expected in 2022.

Eyad A. is not a “big fish,” but for Kayyali, his verdict is a signal “to every cog in the machine, that their role, however small, is going to be held accountable.” For Bashi, this conviction may deter “insider witnesses.” Some of the witnesses that SJAC “had been working on for years were on the verge of coming forward, but they backed out [after Eyad’s conviction].”

This opens a debate about what type of accountability Syrians envision. “Do we want to only go for top leading officials, or are we trying to be inclusive and go for everyone who is involved in crimes?” Bashi asked.

The Koblenz example is “a very good motivation for European countries to push forth on universal jurisdiction cases,” Kayyali said. “Germany, Netherlands, and Sweden have done good work investigating not only Syrian government perpetrators but also members of ISIS,” Bashi said.

The US does not allow courts to exercise universal jurisdiction, but in 2021 several Syria-related cases have taken place given the US nationality of the victims. For instance, Elshafee Elsheikh and Alexanda Kotey, known as the ISIS Beatles, were tried for the murder of four American hostages. Kotey received a life sentence, while Elsheik’s verdict is expected in early 2022.

In 2022, a decision is also expected by the International Court of Justice to open – or not – an investigation on the Syrian Government for gross human rights violations under the Convention against Torture, as requested by the Netherlands and Canada.