Accountability abroad: Mapping Syria-related cases in foreign courts

From the landmark Koblenz trial in Germany to the latest indictment of three high-ranking Syrian regime officials in France, the battle to hold perpetrators accountable for wartime atrocities in Syria is being waged in foreign courts. What kinds of cases are being brought, and where?

25 April 2023

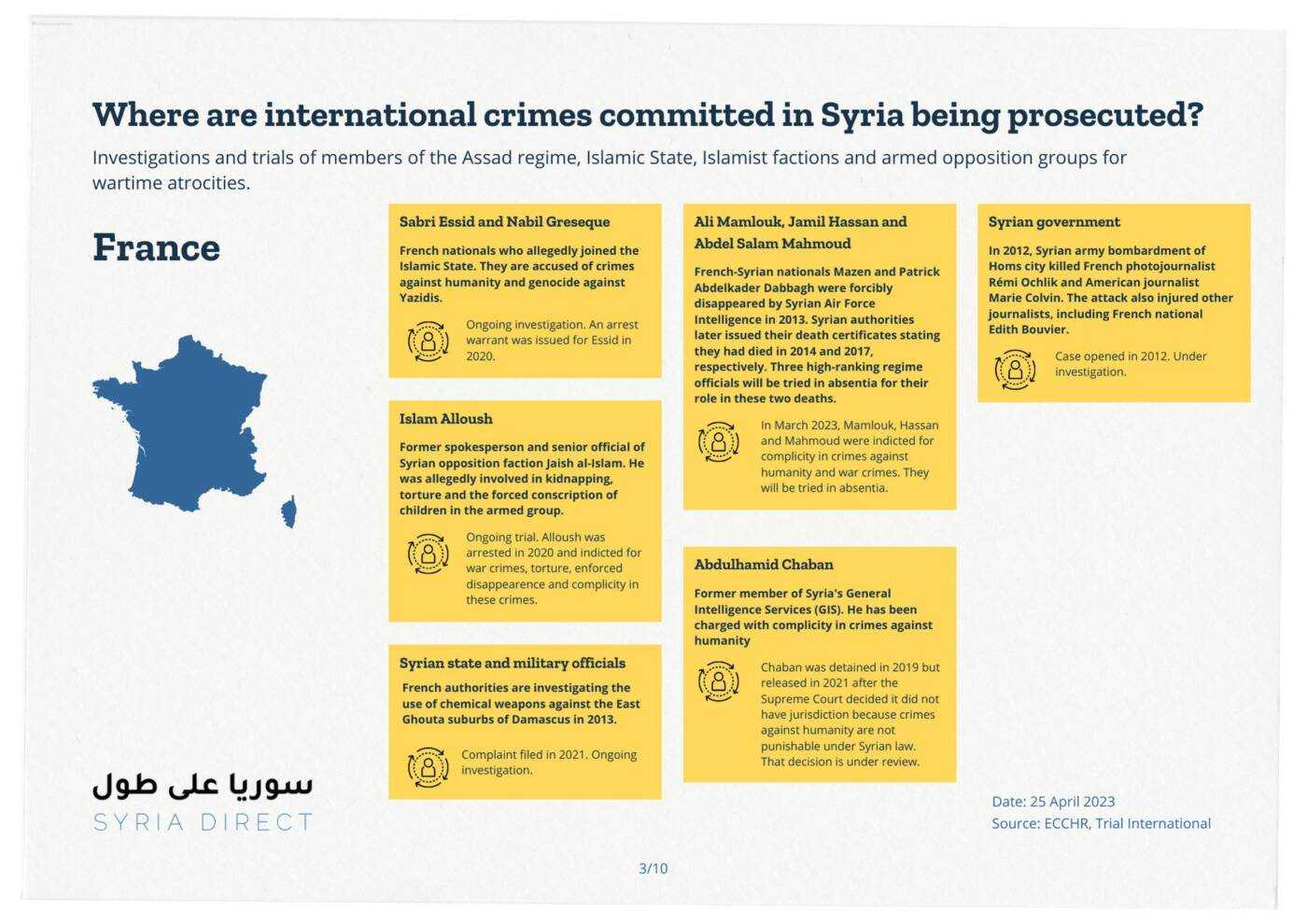

ATHENS – A French court’s recent indictment of three high-ranking Syrian officials for complicity in crimes against humanity and war crimes in the death of two Franco-Syrian citizens has reignited the question of what accountability avenues exist for atrocities committed in Syria since 2011.

Mazen Dabbagh and his 20-year-old son Patrick Abdelkader were detained in 2013 by Syrian Air Force Intelligence in the Mezzeh Airport in Damascus, one of the deadliest detention centers in Syria. They disappeared without a trace. Five years later, the Dabbagh family received two death certificates stating that Patrick died in 2014 and Mazen in 2017. They were among an estimated 14,464 people tortured to death in the country since 2011.

For years, the Dabbagh family sought accountability for their disappearances and deaths. Finally, on March 29, the Paris Judicial Court’s war crimes unit indicted Ali Mamlouk, the head of the Syria’s National Security Bureau, Jamil Hassan, the head Syrian Air Force Intelligence and Abdel Salam Mahmoud, the head of investigations at the Mezzeh branch where Mazen and Patrick were held.

“This decision to try regime officials of this high rank is unprecedented in France,” explained Tarek Hokan, manager of the Strategic Litigation Project at the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), one of the parties in the family’s legal complaint, first filed in 2016.

The three indicted Syrian officials are to be tried in absentia. “I expect the trial to start in a matter of months and since the defendants won’t be in court, the trial won’t take more than a week,” Hokan explained. All the men are under European sanctions and travel bans, and have been the targets of an arrest warrant issued by the French court since 2018.

While the three defendants will not be seated in front of a French judge, Hokan said the verdict will move the fight against impunity for crimes committed in Syria forward “This trial sends a strong message to perpetrators of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Syria.”

The French unit specialized in prosecuting crimes against humanity and war crimes is, according to SCM, conducting 10 investigations related to Syria, including the Dabbagh case.

In recent years, Syrian survivors and family members of missing or murdered people have increasingly taken their fight for accountability to the national courts of foreign countries, mainly in Europe. Syria is not a party to the Rome Statute, the founding treaty of the International Criminal Court (ICC), and Russia and China have vetoed its referral to the ICC by the Security Council.

Cases are often brought using the legal principle of universal jurisdiction or, as in the Dabbagh case, because the victims were themselves citizens of the country where the case is filed.

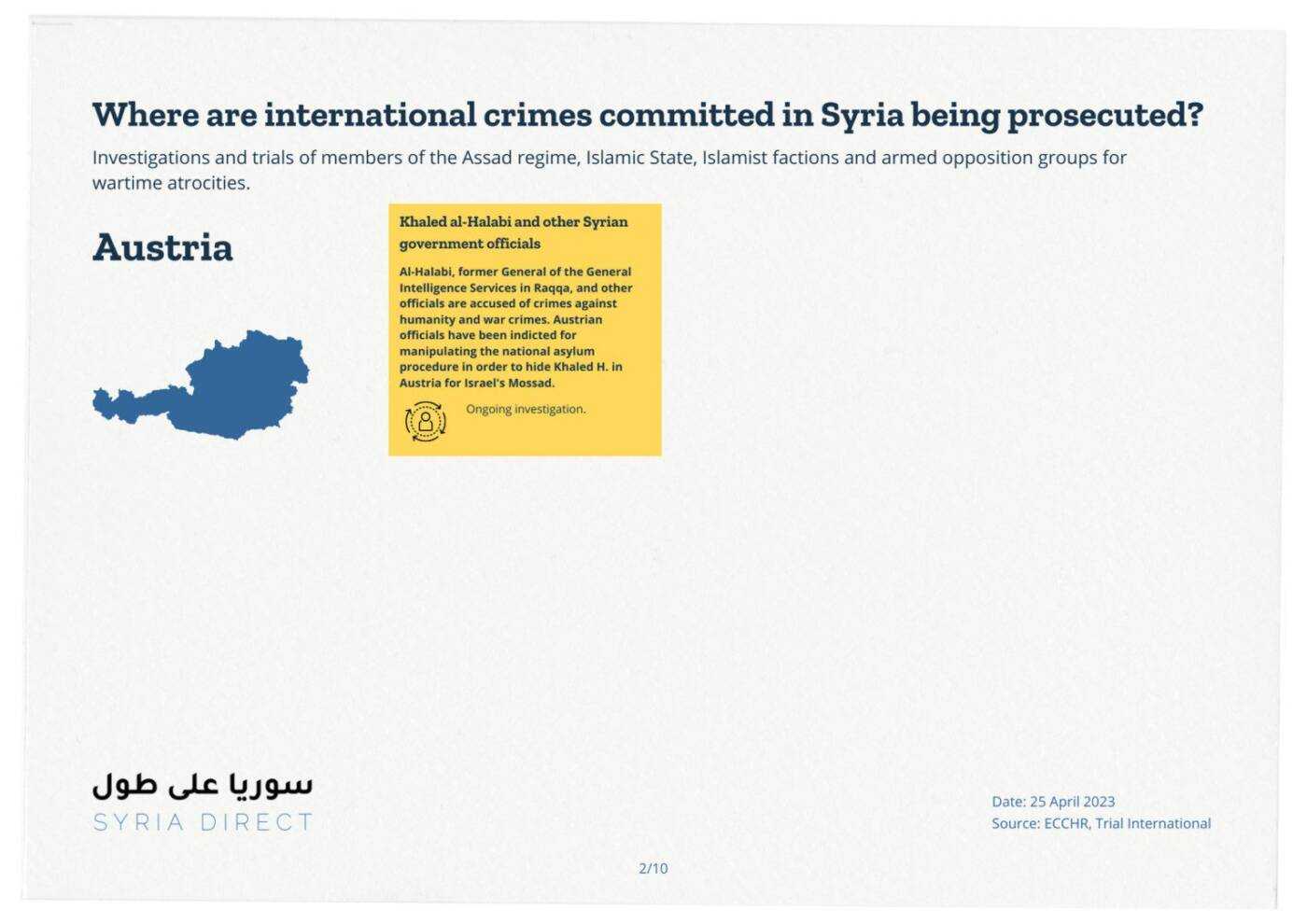

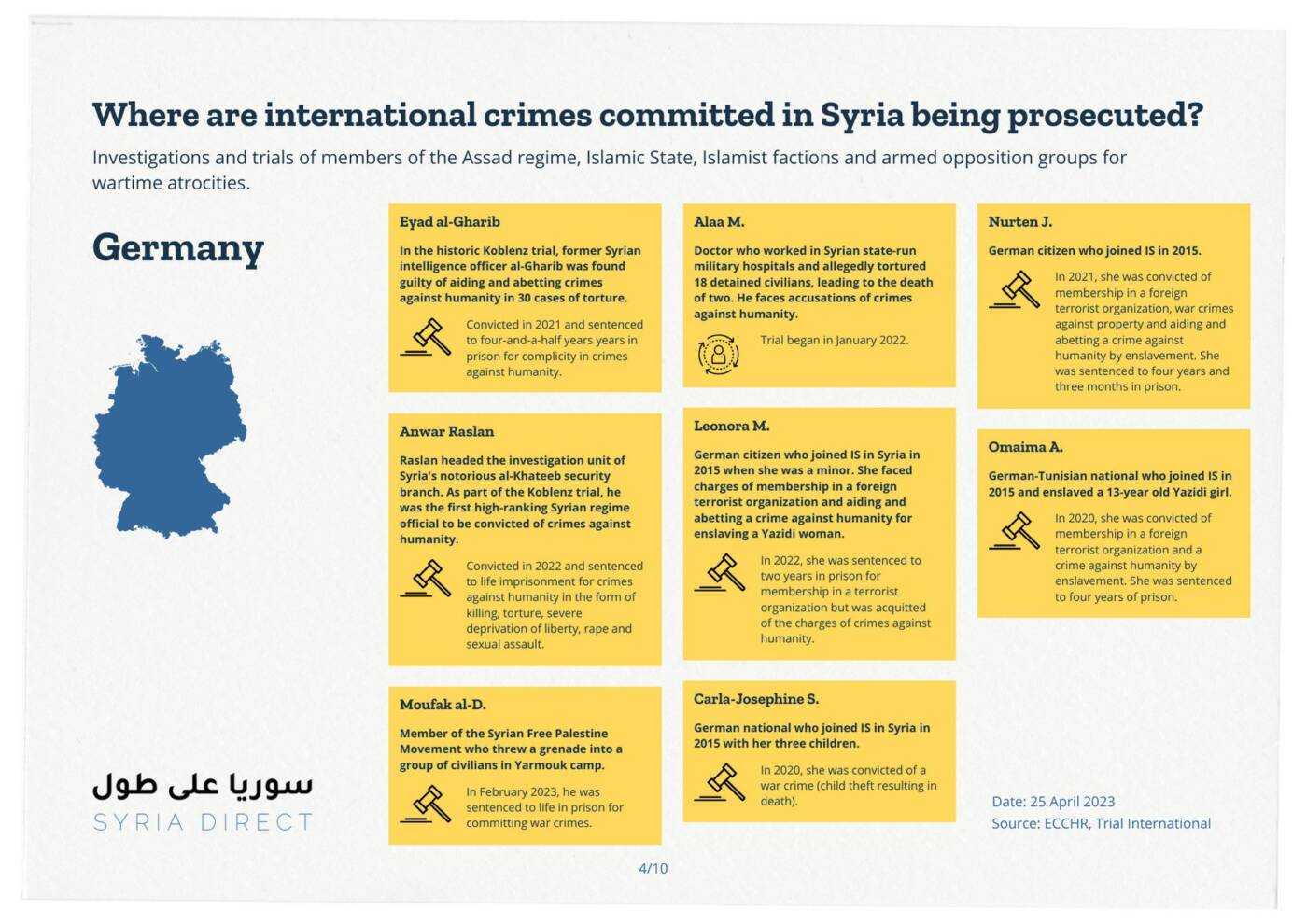

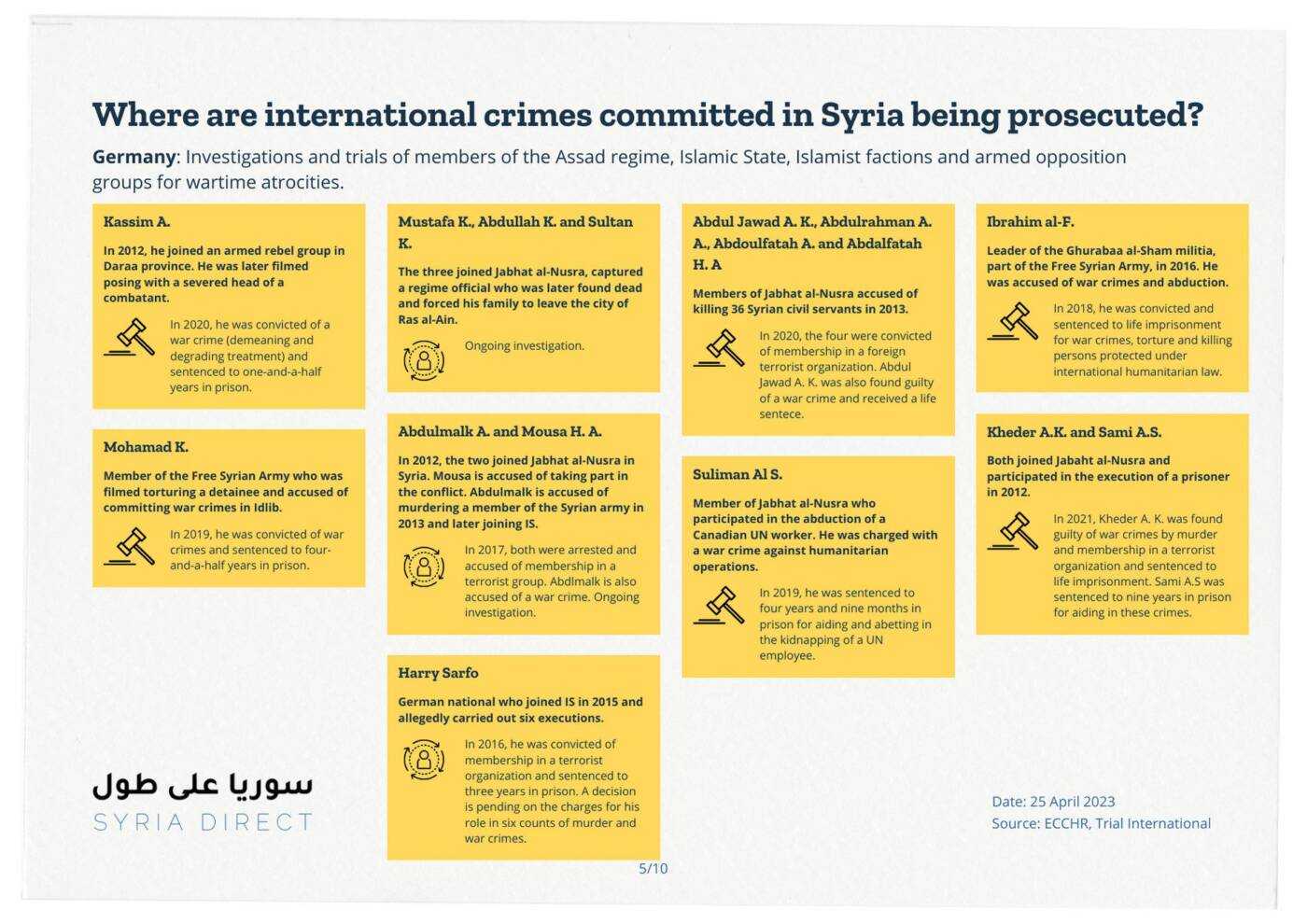

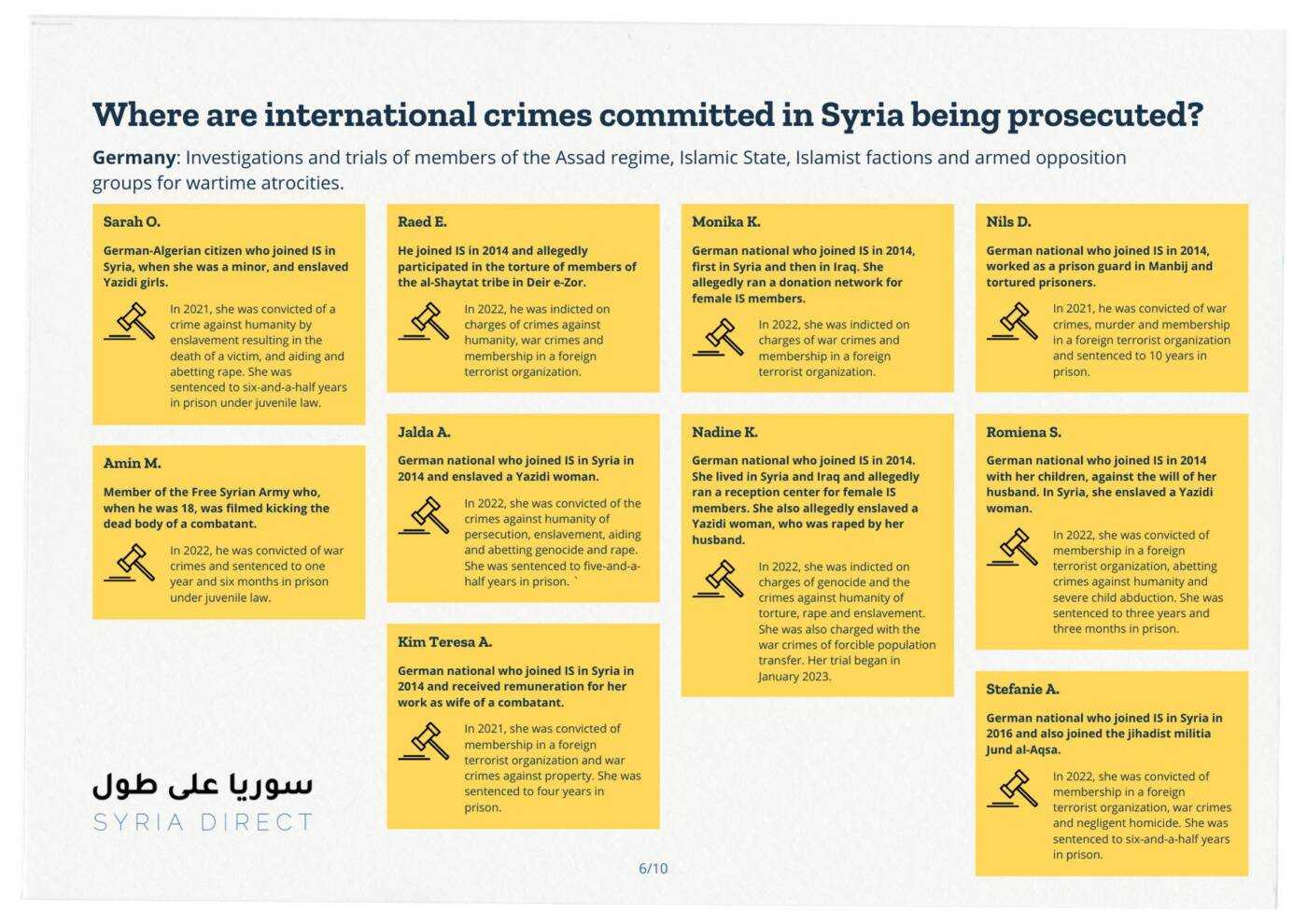

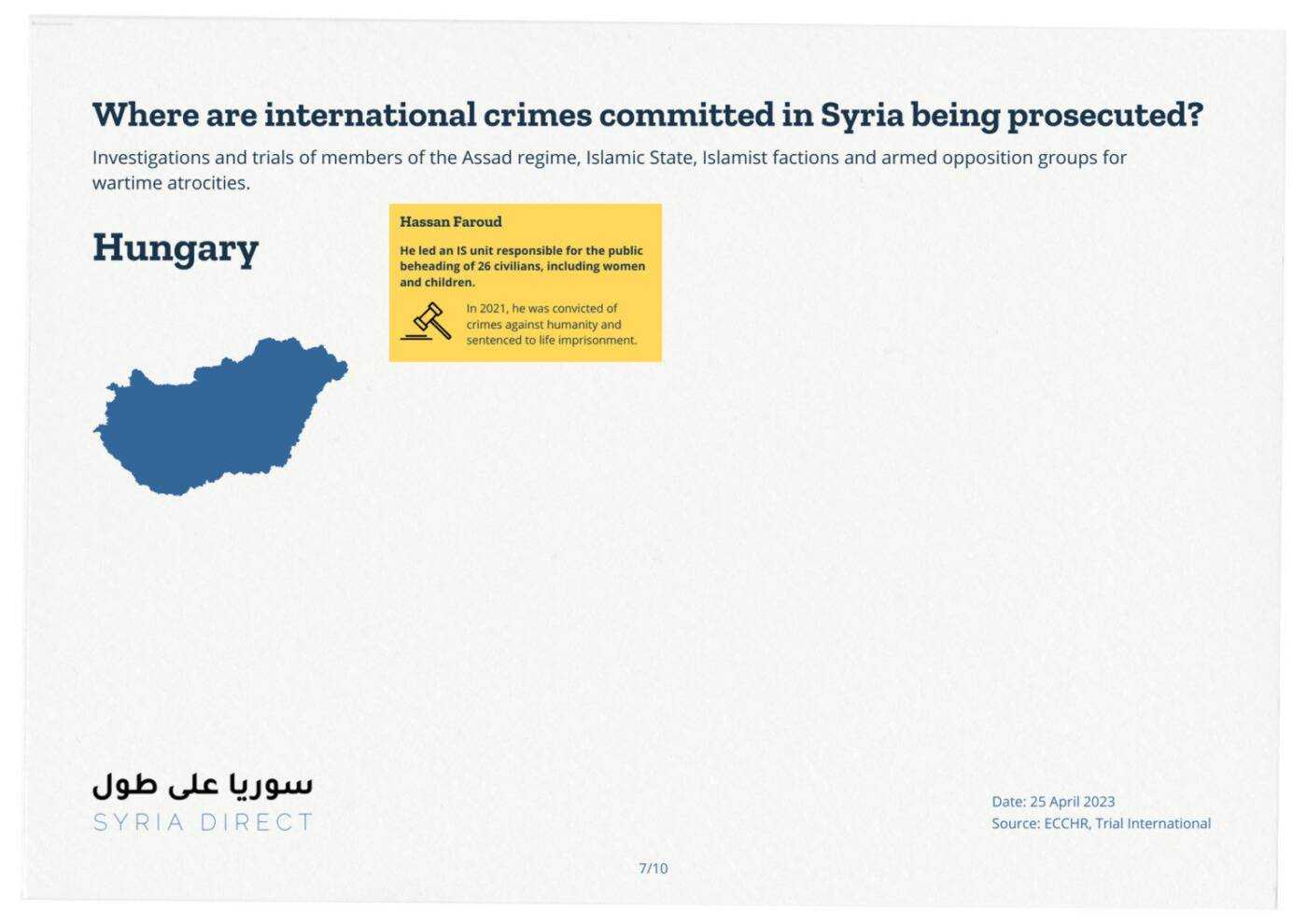

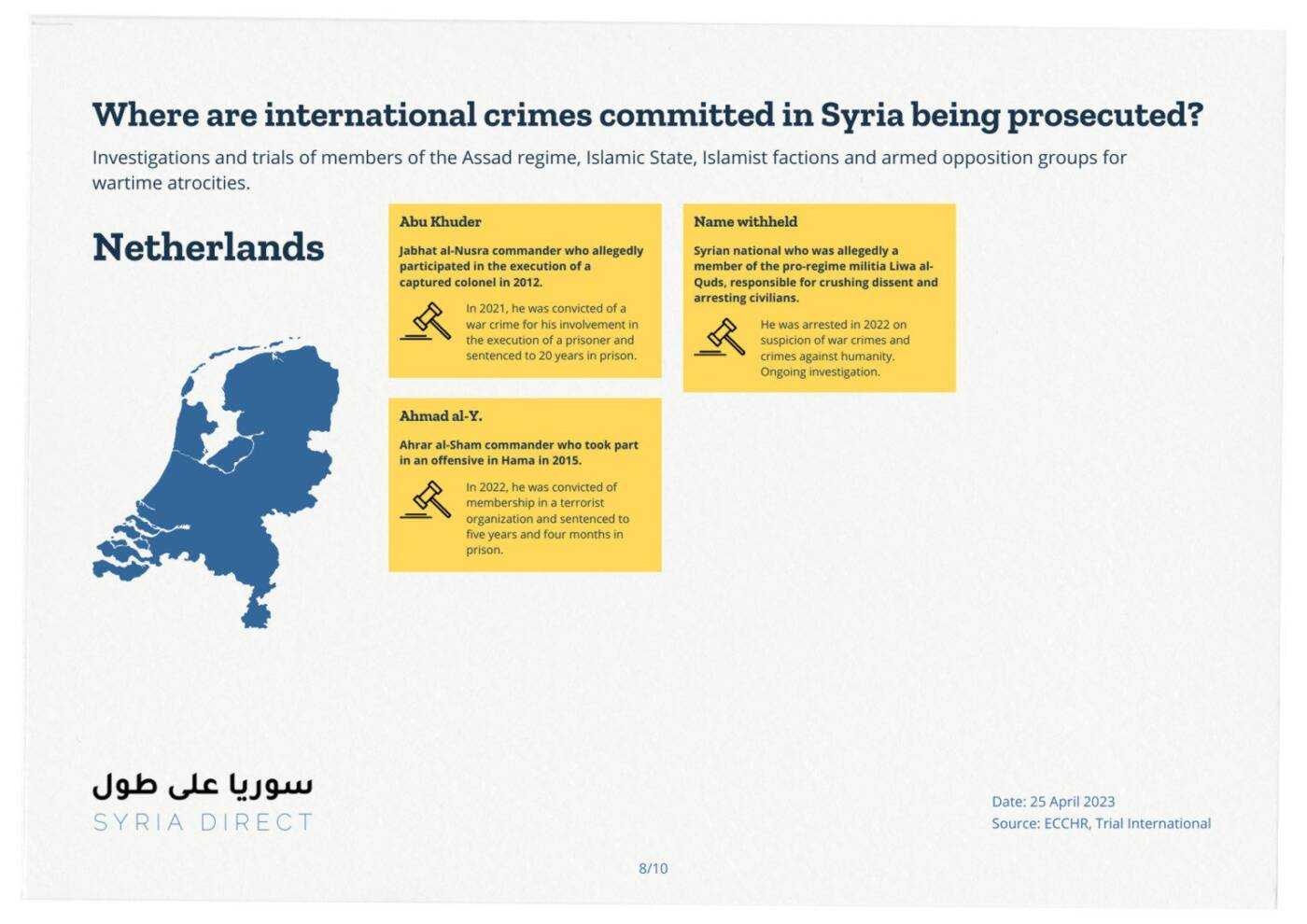

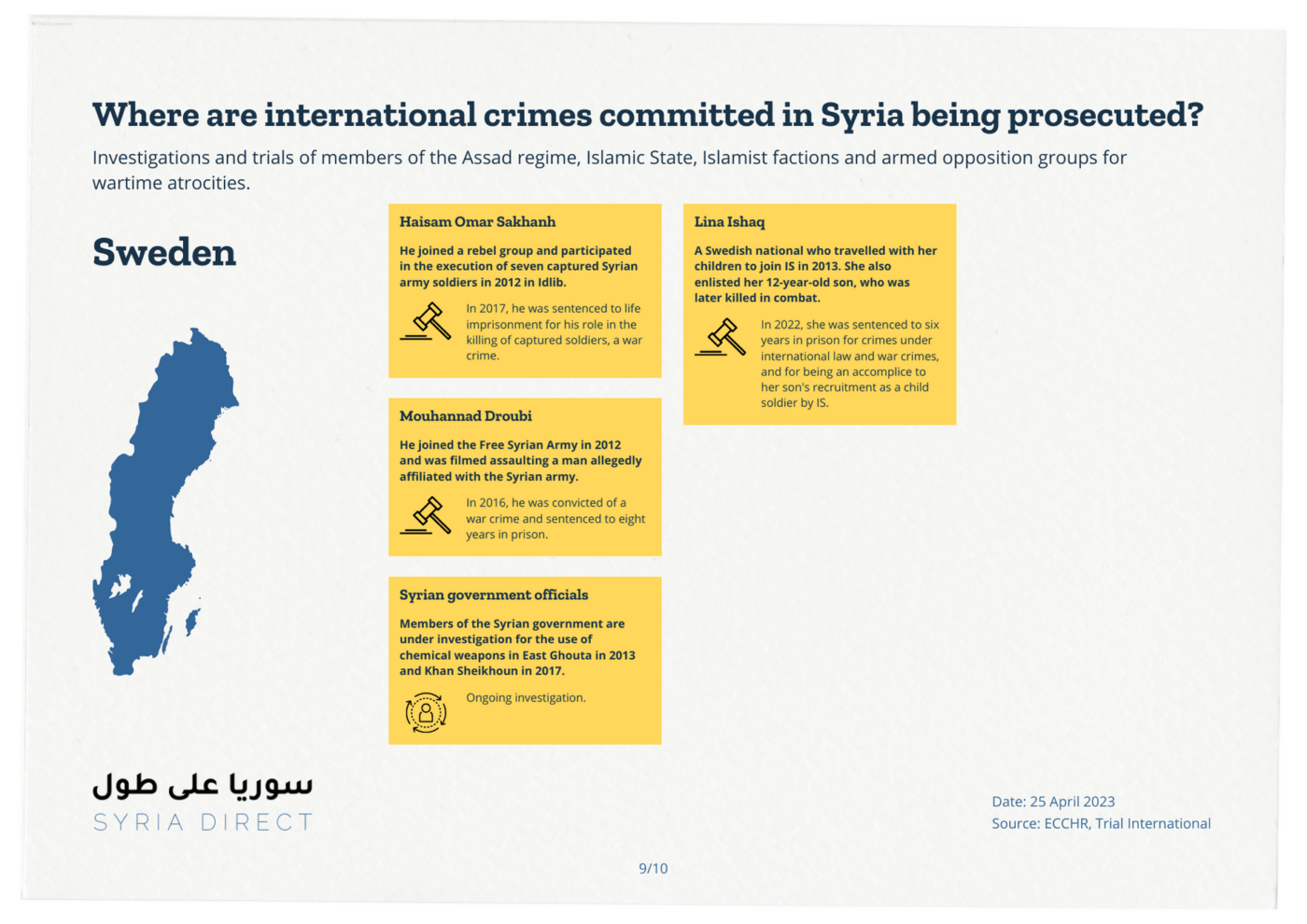

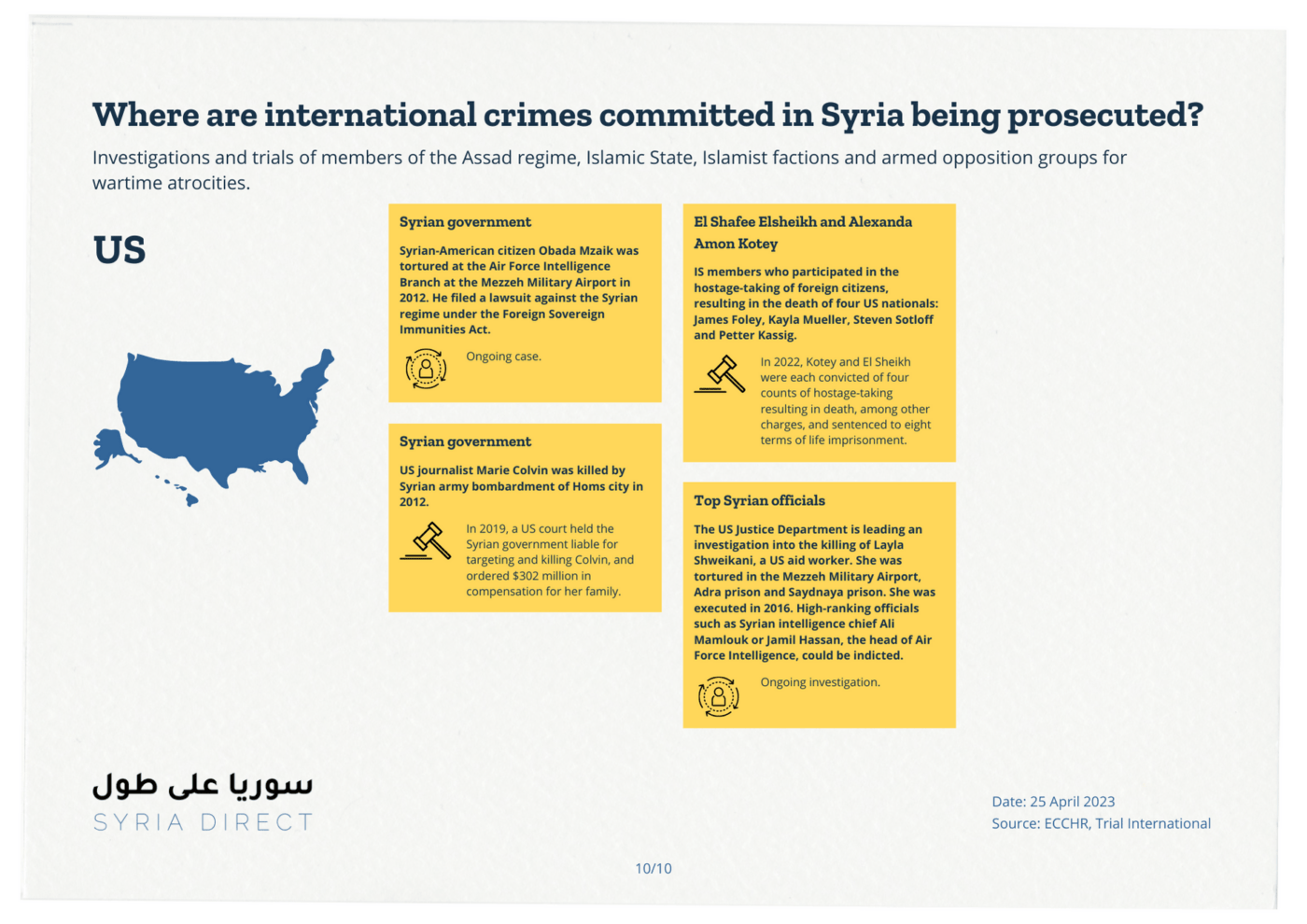

The map below tracks a selection of more than 40 cases filed in foreign courts in recent years related to crimes committed in Syria since 2011 by the Assad regime, the Islamic State and a range of Islamist factions and armed opposition groups.

Map | Where are international crimes committed in Syria being prosecuted? (Syria Direct)

To date, German prosecutors have initiated 50 Syria-related cases. Swedish prosecutors have brought the same number, while France has filed 10. All three countries have also opened structural investigations into crimes committed in Syria. Structural investigations are launched when there is evidence that a crime has taken place but individual perpetrators have not been identified, so the focus is on the structures or groupings of potential perpetrators.

A number of high-profile court cases have relied on universal jurisdiction—a legal principle under which states can investigate grave international crimes committed outside their territory, regardless of whether the victim or the alleged perpetrator are nationals. But individual countries have their own interpretations. France, for example, takes a stricter approach towards universal jurisdiction, requiring more conditions to bring a case to court, while countries such as Germany interpret it more broadly.

In France, the pursuit of international crimes committed in Syria in French courts depends on several factors, according to a guide published by the Syria Justice and Accountability Center (SJAC). If the victim, as in Dabbagh case, is a French national, the court has jurisdiction. If the victim is not French, there could be jurisdiction in cases of torture or enforced disappearance if the suspected perpetrator is in France.

If the suspect is not in France, but is French or resides in France, the court could also have jurisdiction to try the individual for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. However, if the suspect is neither French nor living in the country, the court would not be able to open an investigation.

France’s double criminality principle, meaning that the country cannot try a suspect on charges that are not penalized in the individual’s country of origin, is a major obstacle to accountability efforts in that country, Hokan said. France does not require double criminality for war crimes or torture, but does for crimes against humanity. “In my opinion, this condition makes France a sort of safe country for many criminals,” he said.

Following this doctrine, the Court of Cassation ruled in November 2021 that French prosecutors could not try Abdulhamid C., a former member of Syrian State Security indicted for crimes against humanity, on the grounds that Syrian law did not penalize these crimes. The ruling is currently under review.

Two months after this setback in France, a German court—invoking the principle of universal jurisdiction—sentenced the former head of the investigations unit at Syria’s notorious al-Khateeb security branch, Anwar Raslan, to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity in January 2022.

To date, Raslan is the highest-ranking official to be convicted for his role in state-sanctioned torture in Syria. But with the upcoming Dabbagh trial in France, the list of senior regime figures convicted of major crimes in foreign courts is expected to grow.