Across Syria this Ramadan, incomplete joy and deepened hardship

Amid worsening economic conditions, Syrians throughout the country are greeting Ramadan this year with tighter budgets and “feelings of loss.”

5 April 2022

PARIS — Across a divided country, Syrian Muslims greeted the holy month of Ramadan over the weekend with joy tinged with suffering amid poor living conditions and unprecedented economic deterioration. Making matters worse, the impacts of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have spilled over into international markets, including in Syria.

In the Rukn al-Din neighborhood of Damascus, Fatima al-Shami, 40, has made do with preparing only mentally for Ramadan’s arrival this year. “Everything will be lacking on our Ramadan tables this year,” the mother of three told Syria Direct. She said her family gets by “day to day” and often has to borrow money to pay their expenses.

Al-Shami’s husband, a public sector employee, makes SYP 100,000 a month ($25.70 according to the parallel market exchange rate of SYP 3,895 to the dollar). It is only enough “to meet our needs for a few days,” she said. “The rest of the month, we borrow from here and there.”

This year, al-Shami is at a loss for what to do to prepare food for the Ramadan table. She has to piece together meals for iftar (the daily evening meal to break the day-long fast), suhoor (the pre-dawn meal), and everything in between while “not going over SYP 15,000 [$3.80], the daily amount we’ve budgeted for this month,” she said. Thinking back to her lifestyle before 2011, replicating it today would mean “spending SYP 1 million a month [$256], just for basics,” said al-Shami.

Rising prices

Syrians living in areas controlled by the Syrian regime, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the northeast and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and opposition groups in the northwest largely share similar economic conditions. There is a slight margin of difference in the prices of some basic goods and their availability from one region to another.

This Ramadan was not widely expected to be more difficult than last year. But the fall in the exchange rate of the Syrian pound against the dollar from SYP 2,970 a year ago to SYP 3,895 this year, on top of the removal of government subsidies from hundreds of thousands of people in regime-controlled areas and the repercussions of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have caused greater hardship.

Even before recent factors exacerbated Syrians’ economic difficulties, the country’s economy suffered from “several diseases, primarily unemployment, which is over 80 percent,” said Syrian economic analyst Osama al-Qadi. “More than 90 percent of Syrians live below the poverty line, a significant portion of whom have reached the stage of hunger.”

Al-Qadi said that “basic materials imported from Ukraine, such as corn oil—of which it produces 40 percent of the world’s supply—as well as wheat and other foodstuffs are now missing in the markets. If available, their price will rise exponentially.”

The price of a liter of corn oil in regime-controlled Damascus has passed SYP 18,000 ($11.50). “The cost of a kilogram of rice has reached SYP 9,000 [$2], while it was SYP 3,500 last year,” al-Shami said, “and a bundle of government-subsidized bread has reached SYP 1,300 [$0.30].”

Meat prices have also multiplied. “A kilogram of lamb costs SYP 42,000 [$10.70], compared to SYP 14,000 last year, and chicken costs SYP 14,000 [$3.59] after it was SYP 4,000,” she added.

The first iftar that al-Shami’s family shared this year. The dish of stuffed vegetables (mahashi) on the left was shared with the family by neighbors (a tradition called sakba in Syria). The fattoush, a salad topped with pomegranate molasses and bits of fried bread, cost SYP 8,000 ($2) to make. (Fatima al-Shami/Syria Direct)

Food prices are also up in opposition-controlled areas of northwestern Syria. There, the price of a liter of corn oil has reached 40 Turkish lira ($2.72 according to the parallel market exchange rate of TRY 14.69 to the dollar), while a kilogram of rice costs TRY 15 ($1.02), according to Ali Kharbout, who owns a shop in Idlib city. A bundle of bread now costs TRY 2.50 ($0.17), he said.

Meat prices have risen there as well. A kilogram of lamb sells for TRY 100 ($6.80), double what it cost last year. The same amount of chicken is now TRY 50 ($3.40), up from no more than TRY 20 in 2021, according to Kharbout. The prices of some items “are four times higher than last year, which has weakened demand,” he said, so “the markets are empty of customers.”

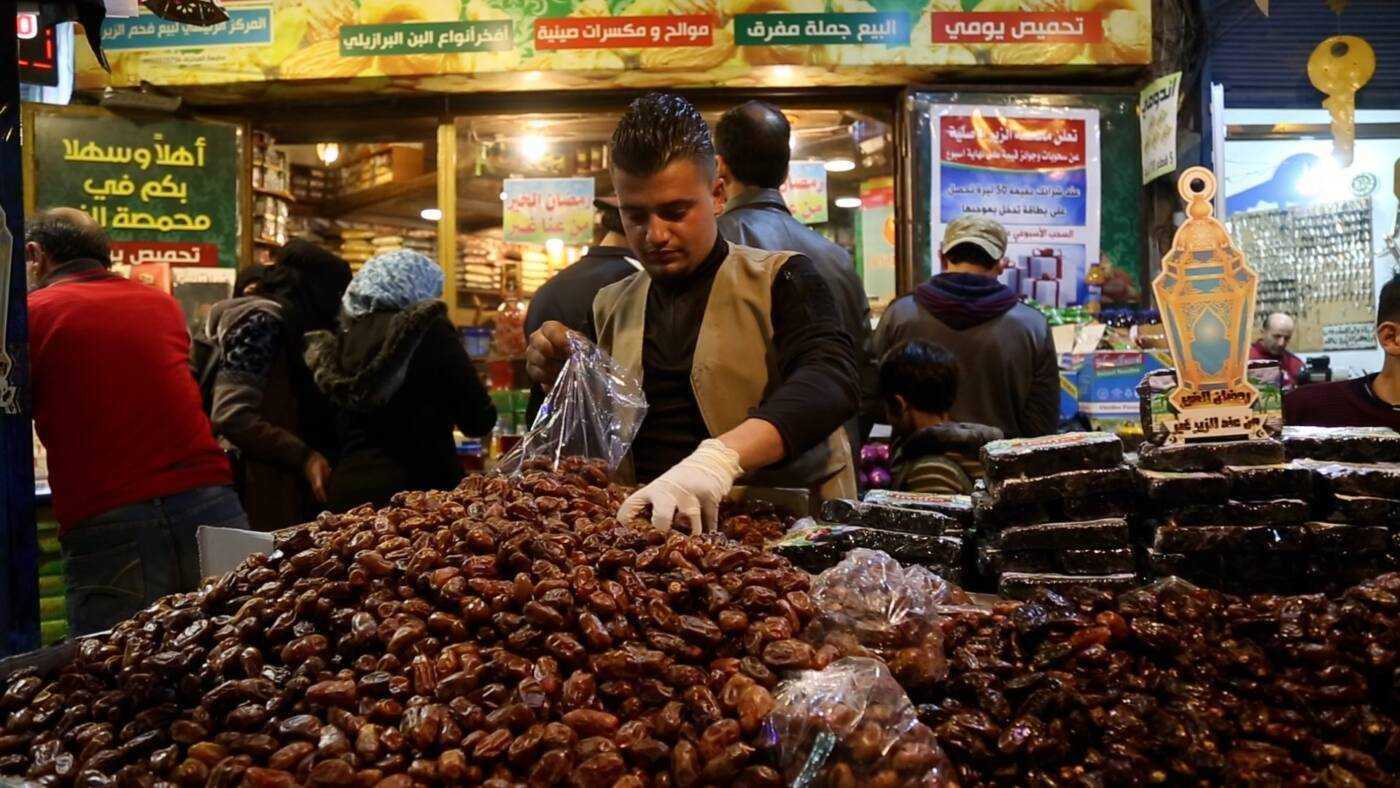

A market in Idlib city on the first night of Ramadan, 1/4/2022 (Ali Haj Suleiman)

Kharbout estimated that a family of three in northwestern Syria would need “TRY 200 [$13.50] a day to cover their basic needs,” while family incomes range “between TRY 30-50 [$2.04-3.40] a day.”

Similarly, the residents of SDF-controlled northeastern Syria welcomed Ramadan amid a clear rise in the prices of basic materials compared with 2021. In the eastern Deir e-Zor countryside, where Ahmad al-Sheheilawi, 32, lives, the price of a liter of corn oil in SDF areas is SYP 10,000 ($2.50), up from SYP 5,000 last year, he said. A kilogram of rice now costs SYP 4,600 ($1), while it was previously 3,200.

The price of flour has also increased. A 50-kilogram sack of flour now costs SYP 125,000 ($32), while last year it sold for SYP 50,000, according to al-Sheheilawi.

Al-Sheheilawi makes $150 a month working at a local oil refining center, which is relatively good in comparison with salaries in regime-controlled areas. But the father of four still struggles to make ends meet. “The salary is not enough for me on regular days, so how will it be for the month of Ramadan,” he wondered.

The al-Sheheilawi family’s first iftar of this Ramadan. The meal cost SYP 6,000 ($1.54) to prepare, and consisted of bulgur with vermicelli, alongside a bowl of lentil soup and some bread. (Ahmad al-Sheheilawi/Syria Direct)

‘Imported inflation’

Regime-controlled areas of Syria have the lowest salaries compared to the rest of the country. The average monthly salary is SYP 100,000 ($25.70), or “the price of two kilograms of meat, meaning an employee suffers poverty in all its miserable details,” said economic analyst al-Qadi. Before 2011, the average monthly salary in Syria was around SYP 15,000, or around $300 at the time.

Syrians’ main problem, from al-Qadi’s perspective, is that they suffer from “imported inflation,” as he put it. “The prices of oil, fuel, energy and raw materials are elevated globally, and the regime importing those goods from abroad is tantamount to bringing in inflation.”

Making matters worse is “economic stagnation inside Syria,” said al-Qadi. One reason for stagnation is “the regime driving away tens of thousands of industrialists and technicians from Syria,” he said. Another factor is Decree No. 3 of 2020, which further criminalized the use of foreign currencies like the dollar while conducting financial transactions inside Syria, increasing the existing punishment to seven years of penal labor. The decree “contributed to freezing economic activity,” said al-Qadi.

Confused spending

For Turki Swied, 45, the arrival of Ramadan coincided with the second month in a row that he has been without a salary. As a result, he had to borrow TRY 400 ($27), most of which he spent, leaving him with TRY 70 ($4.75). That “has to be enough until the end of the month, until [my] work contract is renewed,” he told Syria Direct.

Swied lives in a camp in the Idlib countryside and works at the local Radio Fresh station. But since “my contract with them is as a volunteer, my salary is suspended until the contracts are renewed,” he said.

And so the father of four entered Ramadan “without buying special foods for the holy month,” and the family’s first iftar was “leftovers from the day before, as well as a plate of fatteh,” a dish made with pieces of bread or rice mixed with a garlic yogurt sauce and a protein such as chickpeas or chicken.

For Swied, what is most difficult is feeling helpless in front of his children, who “talk about what they hope to buy for Eid [al-Fitr].” Unable to pay the costs of Ramadan in the first place, he does not dare tell them that “I don’t have the money to grant their wishes,” he said.

In Damascus, al-Shami is struggling to “get through Ramadan without borrowing money from anyone,” she said. She and her husband are unsure “how to divide the monthly salary of SYP 100,000 over the days of the month,” al-Shami added.

Al-Sheheilawi, in Deir e-Zor, said some days “my children and I eat a single meal” of mostly bread. But “even bread, we’re trying to consume less of it after the cost of flour went up,” he said. Under these circumstances, he wondered, “what preparations for the good month are we talking about?”

Ramadan rituals absent

More than any other year, Syrians are trying to reduce their Ramadan expenses. As a result, many Ramadan rituals have disappeared. “We used to wait for the holy month to come with hearts full of joy, and decorate our houses inside and out,” said al-Shami. “Today, everything has disappeared.”

Ramadan decorations have become a “forgotten ritual” for al-Shami and others who spoke with Syria Direct. They are expensive, and other necessities for daily life take priority.

The cost of a “one-meter decorative string of lights is SYP 45,000 [$11.50] in Damascus,” said al-Shami. A light-up Ramadan crescent ranges from SYP 150,000-200,000 ($38-51), depending on the size and type, she added.

Swied, displaced from Kafr Nubl in the southern Idlib countryside, said Ramadan’s arrival “brings up feelings of loss and heartbreak for many displaced families.” There are no Ramadan rituals, “and we are far from our homes and their gardens that used to bring family members together for the iftar meal,” he said.

“Today, we are uprooted from our land. Death has taken our martyrs, and Assad’s detention centers have taken those we love,” said Swied. “We have forgotten the joy and rituals of the holy month, and we forgot its social customs years ago.”

In Deir e-Zor, al-Sheheilawi is nostalgic for the old joy of Ramadan, which “used to bring happiness to our souls,” he said. “Now, people in the area can barely make a living,” he added. What is more, “we’ve come to fear the holy month’s arrival—even though we are aware of its blessing, it is a catastrophe for poor families.”

“Even if someone can buy Ramadan decorations,” al-Shami concluded sarcastically, “they won’t be able to light them with the constant power outages.”

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.