Cinema and acting fuel Syrian refugees’ dreams in an Iraqi camp

In Iraqi Kurdistan, an international film festival is providing opportunities for Syrian refugees to enjoy cinema again and take part in the region’s budding film industry.

12 December 2022

DOMIZ — Calming down the dozens of children running down the aisles of the screening hall seemed impossible. School-age boys and girls flurried about excitedly, squeezing in and out of the main door in swarms, folding and unfolding the theater seats, laughing and poking each other while adults walked in calmly, took their seats and waited for the movie to start.

Eventually, Adil Ebdulrehm and the other volunteers ushering in the audience gave up. “Just wait until the movie starts,” he said, shrugging his shoulders and grinning widely. “It gets worse. They get really excited and spend their time running in and out of the hall. Our main job is to calm them down.”

Equipped with a large inflatable screen, a projector and around 200 red velvet theater seats, the screening hall almost looked like a cinema. The only difference was its location—inside a camp for Syrian refugees in Iraq. Many of the children bustling through the aisles had never been to a movie theater before.

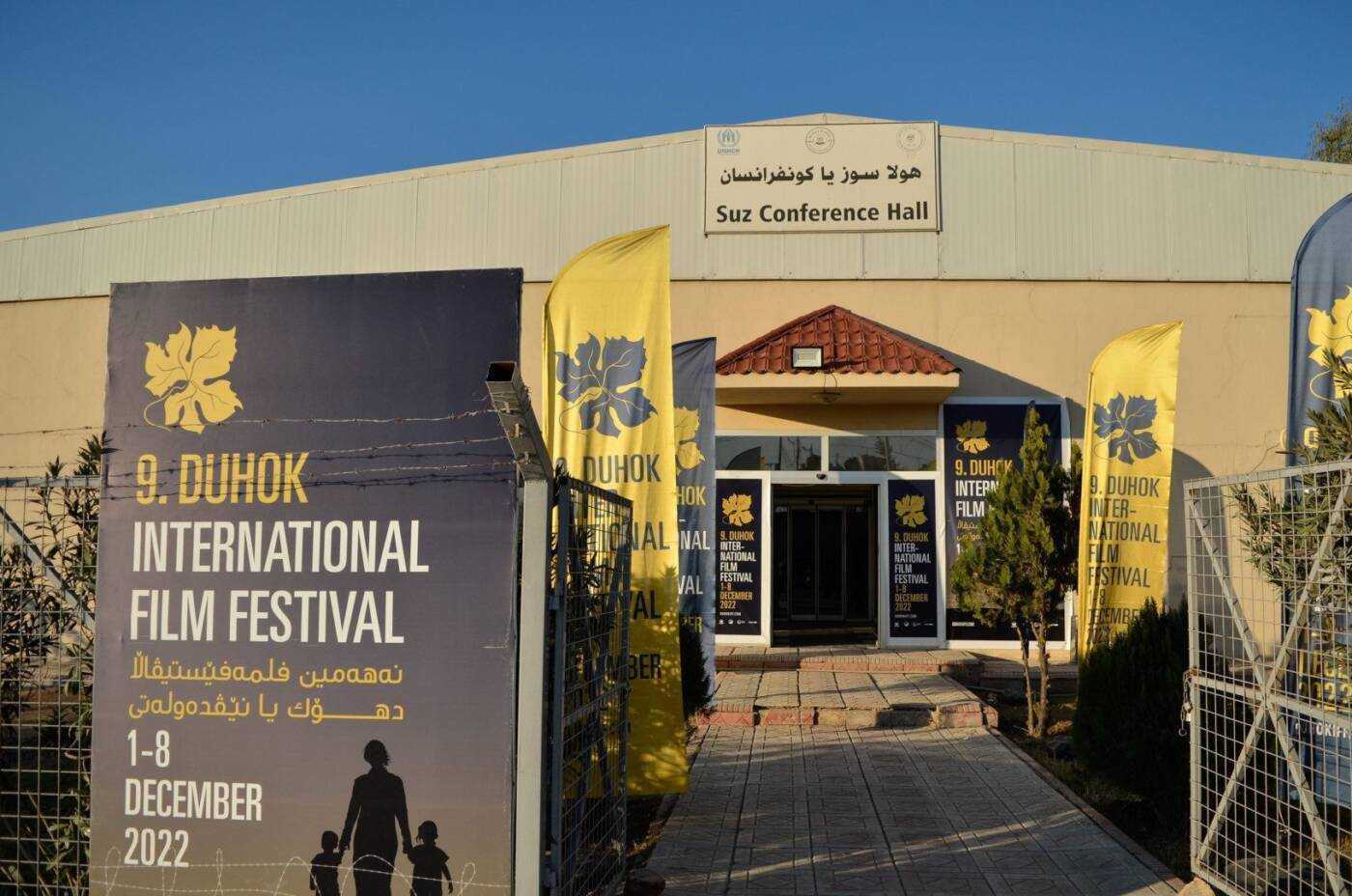

The venue, a large events hall used to host weddings and funerals, was converted into a screening hall over the course of a few weeks for the Duhok International Film Festival, which takes place since 2011 in the city of Duhok, in Iraq’s autonomous Kurdistan region. Each year, the festival showcases dozens of films, bringing together Kurdish filmmakers from the region and the diaspora as well as foreigners.

Up until this year, the films were screened at the University of Duhok and in the city’s only cinema—an aging venue with three small theaters. But the 2022 edition, which ran from December 1st to December 8, was different.

“We decided to screen some of the Kurdish feature films in the Domiz camp, to create a bridge between refugees and the festival,” Shawkat Amin Korki, the festival’s artistic director, told Syria Direct. Domiz I is the largest refugee camp in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). It lies on the outskirts of Duhok and is home to 30,000 Syrian refugees, in addition to around 10,000 more in the nearby Domiz II Camp.

Bringing art to the camp

The decision to bring the festival to Domiz sprang from the theme chosen for this year’s edition, hijra—which translates to “exodus” or “migration.”

“Because of all the things that have happened in this part of the world, because migration has been steadily rising over the last years, because in our region there are a lot of refugee camps and displacement camps, because of the war in Ukraine, migration is a universal theme,” Korki said.

Organizers felt the theme would resonate particularly strongly with the residents of Domiz, Syrian refugees who fled their country over the course of the Syrian war, as well as people living in other refugee and displacement camps around Duhok. But getting this audience to cinemas can be difficult. “The camps are a bit remote, and it’s hard for families to travel to the city every day to watch the films,” Saman Mustafe, the coordinator of the festival, told Syria Direct. “That’s why we decided to bring the films to them, in the camp.”

This was easier said than done. Finding venues to screen the festival is always a challenge, even in Duhok city, where there is only one commercial cinema. In Domiz, the only option was an empty hall that had to be equipped from scratch. “Still, we thought it would be better than nothing,” Korki said.

A conference hall was turned into an improvised cinema in Domiz I Camp, in Iraqi Kurdistan, 6/12/2022 (Lyse Mauvais/Syria Direct)

A packed room

These efforts have paid off, and the screenings proved popular. “The hall is always full every day,” Mustafe said during the festival’s one-week run. “We were impressed with the audience.” Most of those attending were families and children, although the selected movies—slow-paced feature films and documentaries—could be difficult to enjoy for the youngest members of the audience.

Filmgoers interviewed by Syria Direct after the December 6 screening of Before the Night, a feature film produced in Turkey’s Kurdish region, spoke very positively of the festival, although some were uneasy about movies that challenged prevalent cultural and social norms.

“I really liked tonight’s film, and I thank the organizers for bringing it to us,” said Ramadan, a young man in his twenties who attended a screening for the first time on December 6. “But there were some scenes that shouldn’t have been in the movie.” One scene that night drew gasps from the audience when a large painting of a naked woman appeared on screen.

Ramadan may also have been referring to the following scene, in which the main character, a young Kurdish woman, lies in bed with her female lover while drinking alcohol. But Rojen, an 18-year old woman who came to every day of the screenings, said she wasn’t shocked. “These stories happen everywhere around the world.”

An opportunity to act

Over the years, the festival has drawn many foreign and Kurdish filmmakers to Duhok, and many have returned to shoot movies in the area. This has created opportunities for some in the camp, like Sawsan, a young camp resident in her thirties who has worked as an extra in several movies over the past three years, getting paid around $13 per day for occasional shoots.

“I have wanted to try acting since I was a child, but I could never ever imagine that this dream would come true one day, especially after getting married and having children,” the mother of three, who comes from the countryside of Qamishli in northeastern Syria, said. One of the most memorable sets she was part of was The Bride, a 2022 fictional drama about a young European woman who marries an Islamic State (IS) fighter and faces trial in Iraq for being part of IS. Sawsan and around 50 other women from Domiz camp were hired and asked to play the role of other IS spouses and mothers awaiting trial.

“When I put on my clothes for this role, I was scared at first. I had never worn a niqab before,” Sawsan recalled. “It was a strange experience.”

Cast in the same movie as a Kurdish soldier, Ali Haji has seized on acting jobs as an opportunity to reconnect with his dreams and escape boredom and unemployment in the camp. “I have played in several films before, but The Bride was my favorite among all because I played a soldier,” Haij said, his eyes beaming with excitement. “I was wearing the uniform of an Iraqi soldier and guarding IS prisoners. I loved that role, because I used to be a peshmerga, I was even wounded at war. But I left the army, and there isn’t much to do now.”

Volunteers from Domiz I camp ran daily screenings of the Duhok International Film Festival inside the camp, 6/12/2022 (Lyse Mauvais/Syria Direct)

An emerging acting community

Filming in Domiz has also provided an outlet for the camp’s small but growing acting community. Among its emblematic actors is Muhammad Muselmini, known under his artist’s name “Qanjo”, a Syrian Kurd from al-Qahtaniya (Tirbespî) who has been acting for over 50 years, first in Syria and then in the camp.

“Over there in Syria, we had no space for acting, there was no freedom,” Qanjo said. “The first film I was part of in Syria, the next day we had someone from the security services in front of the house, I swear to God.” In this restricted artistic landscape, Qanjo preferred to keep a low profile and directed his energy towards small skits and plays less likely to attract unwanted attention. “We performed inside houses, inside our community, and during celebrations, for example during Newroz and other Kurdish festivals,” he added.

Since arriving in Domiz in 2012, Qanjo has maintained his passion for acting, alongside two day jobs. He is part of a small acting group that performs in comedy skits and plays inside the camp, as well as in YouTube videos. Acting, for him, forms an important link between life in the camp and the outside world. “The habits we have here are different, the difficulties we face here are different. As we perform, we have an opportunity to show our life and our own reality to the world,” he said.

But this opportunity is not afforded to all in the same way, and acting remains socially stigmatized in some families, particularly for women. “I don’t hide anything from my husband or our families, and I am very grateful to my husband with all my heart that he is not obstructing this dream,” Sawsan said. “ But my family is not entirely supportive of this—it’s a mix.”

Despite his own love for acting, Ali is uncomfortable with the idea of his wife performing in front of a camera. “I don’t want her to act, because in our community we see it as a shameful thing if a married woman leaves the house to work—it means her husband doesn’t provide enough,” he said. “If she really wants to work I might not go against it, but not acting because everyone will see her, know her and talk about it.”

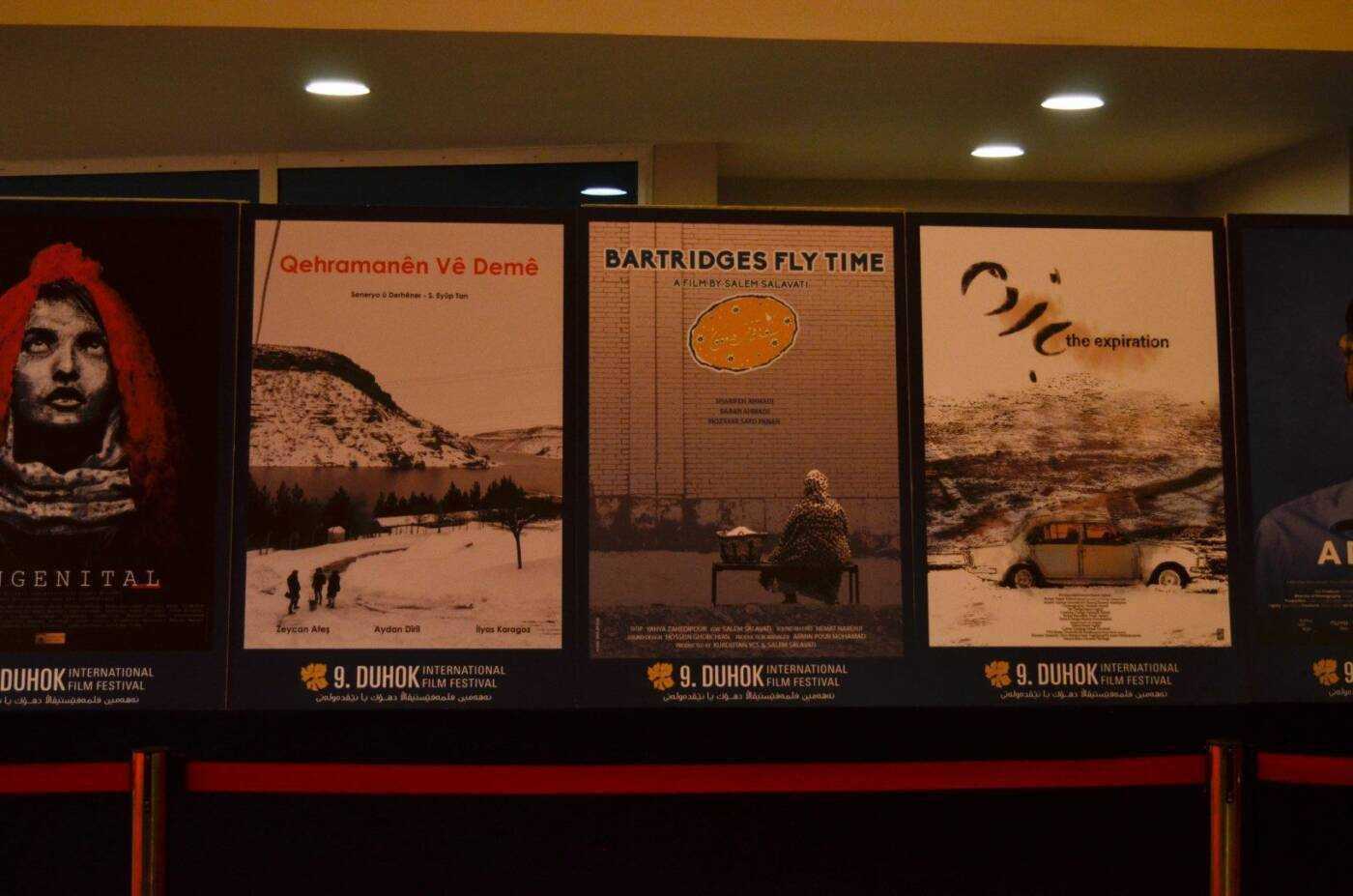

Posters of some of the movies screened at the Duhok International Film Festival from December 1-8, 6/12/2022 (Lyse Mauvais/Syria Direct)

Despite these mixed reactions, the acting community in the camp has grown year after year thanks to the presence of the festival, which has created new artistic connections in Domiz around filmmaking, and opened new doors for some of the residents.

Bringing the movies to Domiz this year is one more step in that direction, allowing residents to access a new artistic universe and pursue dreams that could otherwise be outside their reach. “We are really happy that the festival takes place here this year,” Qanjo said. “We really feel that we haven’t been forgotten. People are thinking about us.”