Community in the collapse: Syrian LGBTQ+ refugees carve out their own havens in Beirut

Through their own safe spaces and mutual aid, Syrian LGBTQ+ refugees navigate a triple nightmare: Lebanon’s economic collapse, aid budget cuts and a worsening climate for queer people in the country.

31 January 2023

BEIRUT — Loujain has proudly decorated her living room with pictures from a recent photo exhibit in which she told her story as a Syrian transgender woman. The images cover the walls of the apartment she shares with her boyfriend in Beirut, a safe space she has carved out for herself after years of struggle, homelessness and torture in a Syrian prison.

Danny*, in another part of the city, only has one picture hanging in his house: a portrait from his university graduation back in Syria. It is the only reminder he keeps of his past, before he transitioned. For the past three years in Lebanon, he has built a life as the man he is, “just Danny,” he said.

And Maram* has made a home with her girlfriend—surrounded by a community of friends—that she has longed for since she was a teenager in Syria. It is a hard-won happiness, three years after divorcing the man she was forced to marry and surviving death threats and a kidnapping by her family.

The three have, in their own ways, created spaces where they can live and be seen on their own terms in Lebanon—a country they all consider safer than Syria, but where all still struggle to be themselves the minute they walk out their front door.

Lebanon’s economic collapse has hit its most vulnerable communities—like LGBTQ+ refugees—particularly hard, and contributed to a worsening climate for the rights of sexual and gender minorities.

But while the need for economic support and protection rises, aid from international NGOs is shrinking for all refugees in Lebanon due to an increase in global need. This is particularly worrying for LGBTQ+ refugees, many of whom may not have the same support from family and community networks. To help fill the gap, informal solidarity networks are mushrooming to ensure LGBTQ+ refugees stay afloat in Lebanon.

‘I thought I was the only one’

Loujain knew quite early in her life that she was different from the rest of her friends. Her family did not understand why she—in their eyes a boy—kept her hair long or played with girls.

“When I was 12, I’d leave my parents’ house dressed normally, then go to my friends’ houses and dress however I wanted,” the 26-year-old recalled. Once her family found out how she dressed outside the house, they banned her from leaving home. “My friends called me on the phone and asked for Loujain, and my family was like, ‘Who is Loujain? What’s that name?’ They beat me and detained me at home,” she said.

Eventually, Loujain fled her family’s house in Damascus and stayed with different friends. A year after war broke out in Syria, she escaped to Lebanon, where she met her boyfriend—who is also Syrian.

“The year before I came here, I realized there were people like me [who were trans]. I thought I was on my own, unique,” she said.

Loujain at her home in Beirut, 26/01/2023 (A. Medina/Syria Direct)

Maram also thought she was an exception. “I always knew I was a lesbian, but I didn’t know that there were people like me,” she said. “I had a crush on my teacher at school. I didn’t tell anyone. I would phone my teacher and she didn’t understand what I wanted…actually, myself I didn’t know,” the 30-year-old said, laughing.

Scrolling through Facebook, she realized she was not alone. “I discovered there were people like me. I wanted to live my life as I wanted, but I was waiting for an opportunity,” Maram said. But in 2013, a year after fleeing to Lebanon with her family, she was forced to marry her cousin.

Still, she kept a parallel life on Facebook, where, in 2018, she started chatting with a woman living in another country in the region. They fell in love, and in 2020, Maram divorced her husband. But when he found out about her sexual orientation, he told her family and everything fell apart.

“My family threatened me because of my sexual orientation,” Maram said. She fled, but relatives abducted her and imprisoned her at the family’s home for a few days before she managed to escape. She has not had any contact with them since 2021. That year, after four years of a long-distance relationship, Maram’s girlfriend traveled to Lebanon, and the two have been together ever since.

Danny, who is a trans man, was 14 years old when he told his mother he wanted to marry a girl at his school. “She told me to forget that, because I’ll marry a boy,” he remembered, and had a talk with him about male and female bodies and reproduction. He had expected that, when he grew older, his body would change and develop in the same way as other boys. “I was in shock,” he said. “I started crying.”

Danny in Beirut, 23/01/2023, (A. Medina/Syria Direct)

Danny’s parents took him to a therapist, who told the family he was transgender. Danny’s parents accepted their son.

“My parents were open-minded, they told me: ‘Once you finish university, just leave this country,’” he said. For a while, he lived a simple life. He had short hair, dated a woman, his family referred to him as Danny, and nobody asked questions.

Danny comes from a well-off family that supported the regime after the revolution broke out in 2011. Both his parents were killed due to the war in 2015, within a few months of each other.

After losing his parents, Danny was able to finish his studies and found a well-paying job. But in 2020, immediately after he underwent surgery to masculinize his chest, “problems started,” he said. “People started talking, and state agents called me for interrogation.”

The Syrian Penal Code outlaws “unnatural sexual intercourse” with up to three years in prison, and LGBTQ+ individuals can be prosecuted under other charges like disturbing public order. During the war, gay and bisexual men, transgender women and nonbinary Syrians have faced sexual violence from both state and non-state actors, according to a 2020 Human Rights Watch (HRW) investigation.

A week after Danny had surgery, he fled to Lebanon, a country comparatively safer than Syria for LGBTQ+ people, but in the grips of an economic disaster.

More need, less funds

Since Lebanon’s 2019 economic crash, three-quarters of the population have plunged into poverty, and 90 percent Syrian refugees into extreme poverty. But in 2022 and 2023, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) cut $180 million in cash assistance for refugees in Lebanon, Jordan and Yemen due to funding gaps—largely due to an increase in the number of displaced people worldwide following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Maram, Danny and Loujain are all registered with UNHCR but none are currently receiving cash assistance.

In January, Helem, one of the main LGBTQ+ rights organizations in Lebanon, suspended its UNHCR-funded refugee cash assistance program. Executive Director Tarek Zeidan said the decision was, in part, made because of insufficient funding to meet the community’s needs.

Syria Direct asked UNHCR if its protection cash program—which includes support for LGBTQ+ refugees, among others—has been reduced. Spokesperson Paula Barrachina said the agency does not have “the specific breakdown figures.”

In 2020, Helem supported 500 refugees, 40 percent of whom requested cash assistance. In 2021, 90 percent of the 2,500 refugees the organization supported requested cash assistance.

Because UNHCR aid was earmarked for refugees, Helem also had to “fundraise separately in order to try and meet the demands of the local host communities, in order to avoid accusations of bias,” Zeidan said. “The policy of UNHCR only mandating that their resources go to refugees without another UN agency stepping up to make sure host communities going through the same exact issues are also not taken care of, is unacceptable,” he added.

Zeidan also denounced what he described as structural problems within the humanitarian response. “Many aid providers in Lebanon were no longer providing aid to the [LGBTQ+] community and instead were saying ‘go to Helem,’ which is incredibly harmful because it creates de facto segregation,” he said. “Human beings, regardless of who they are, should be able to receive aid.”

And the structure of humanitarian crisis response itself can operate in a “homophobic and transphobic” way, Zeidan argued. “For example the [World Food Program] WFP relies on faith-based organizations in order to do most of its food kitchens, and many LGBTQ+ people are not comfortable going to a faith-based organization due to perceived discrimination,” he said.

The three Syrians Syria Direct spoke to have all received aid from some source—whether the UNHCR, Helem or another organization—in the past, but said it fell short of what they needed. When Maram was threatened by her family in 2020, she reached out to Helem for support. “They should have had a safe space for me to stay a few days, but instead they gave me 1.8 million LBP (approximately $225 at the time) for three months,” she said.

Fearing her family’s threats, she was afraid to walk on the streets, or even go to work. UNHCR provided her with legal assistance, cash assistance for six months and therapy, which helped her get back on her feet.

Today, unable to afford rent on their own, Maram and her partner share an apartment with another LGBTQ+ Syrian couple. With Maram’s work as a cleaner and her partner’s occasional jobs, they still struggle to cover their $100 rent.

In 2018, just before Lebanon’s economy’s meltdown began, Loujain was already struggling. She became homeless and, unable to make ends meet, returned to Syria—only to be detained two weeks later.

“I was with my friends at a party, I was wearing an amazing dress, and you know we are banned in Syria,” Loujain said. Police raided the place and detained her and her friends. “I spent three months in Adra prison in Damascus. I was tortured because I was trans,” she said.

When she was released, Loujain returned to Lebanon. She has not gone out dancing ever since. “I got a phobia of dancing, after I was detained. I got scared,” she said.

Back in Lebanon, things are still hard. Loujain said she has not received UNHCR assistance. Her boyfriend’s intermittent work, and occasional aid she receives from an NGO, is their only source of income. As a result, she had to stop her hormone treatment two years ago.“I couldn’t pay for hormones, first I had to eat and drink,” she said.

Danny arrived in Lebanon on foot in 2020, one week after having surgery. “My T-shirt was soaked in blood, the wounds were infected,” he said. A few days later, he contacted Helem for help. The organization gave him 400,000 LBP ($50 at the time)—but his total medical bill (doctor fees, X-rays and medicine) was 7 million LBP ($875 at the time).

He works in several shops and earns 6 million LBP ($105 at the current exchange rate) a month, which covers his $80 rent, utilities and hormone treatment. But he cannot afford the $55 expense of the regular blood work he needs to monitor his testosterone levels and liver function.

Danny received six months of cash assistance from UNHCR when he first arrived, but then it stopped. “I told them I need winter assistance or food, but they only give to families, and I am alone,” he said.

Mutual aid

In the last couple of years, LGBTQ+ activists in Lebanon trying to keep their community afloat have created several initiatives based on mutual aid—a term with roots in anarchist political theory that refers to reciprocal community support and solidarity. For security reasons, these networks maintain a low profile and function mainly via word of mouth, or through Instagram and other social media.

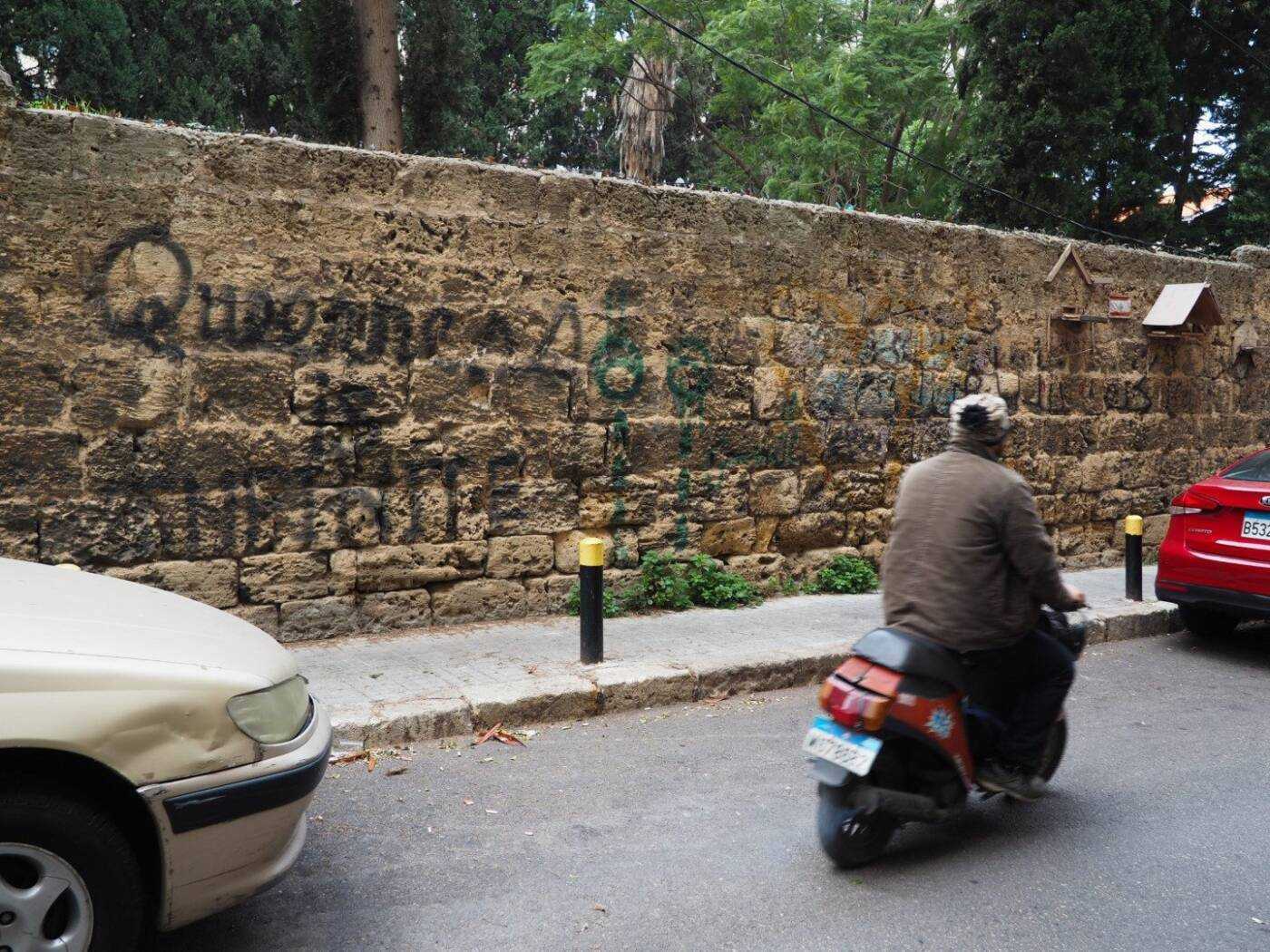

In 2020, Luay* and seven other LGBTQ+ people in Lebanon created one such group: Queer Mutual Aid Lebanon. Through raising funds online and a few grants, they provide cash assistance for LGBTQ+ people in need. They focus “specially on queer and trans Syrian refugees, who we have found to be very much at the intersection of a lot of oppressive structures, including neglected by the larger NGOs that deal with the LGBTQ+ community issues,” Luay said.

The network has an emergency payment program for people that need to find safe housing after being evicted, or face a medical bill or debt, and a monthly support program offering $150 to cover basic needs. In the past two years, they have distributed $50,000.

“If we can’t support a person financially, we try to do a fundraising or connect them to another NGO, we try not to limit ourselves to our budget. We see mutual aid as a tool and a way of organizing that’s contrary to the NGO structure,” he said.

They also try to support in ways that go beyond money. “We also have logistical, emotional and psychological support—we try to form a relationship with these people, loneliness is a massive issue within the queer trans community,” he said.

A shrinking queer space

For years, Beirut has been thought of as a relatively safe space for LGBTQ+ people. “You have certain queer spaces, queer mutual aid networks—they offer some sort of solace for the community. I don’t think that’s very present in the MENA region in general,” said Hussein Cheaito, researcher at The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP).

But Cheaito described the “safe” label as outdated. It is not “safe meaning that I can be visible, I can be myself, I can love who I want to love out in the open without feeling that I will be ostracized or penalized for it…this labeling is just a way to tone down the brutality of the system,” he said.

The Lebanese Penal Code punishes sexual relations “contrary to the order of nature” with up to one year in prison. The law has not been applied in years, but is kept as “a way to further silence and ostracize, to always keep us on the edge,” Cheaito said.

And under the economic crisis, the LGBTQ+ community has been pushed further to the edge. “In times of crisis, minorities—which includes queer people but also women or people with disabilities—are ostracized and burdened with the failure of the states and financial economic system, as if they engendered this shortage in policy making,” he said.

The pressure against the LGBTQ+ community has intensified lately. In June 2022, a right-wing Christian group destroyed a rainbow flag decoration set up in Beirut for Pride month.

View this post on Instagram

In response, Lebanon’s Ministry of Interior banned gatherings by the LGBTQ+ community—a ban that was reversed by a court in November. And in January, police officers were accused of extorting gay men on dating apps. “This rising threat of erasure is unprecedented,” Cheaito said.

Through their own safe spaces and mutual aid, Syrian #LGBTQ+ refugees navigate a triple nightmare: Lebanon’s economic collapse, aid budget cuts and a worsening climate for queer people in the country.

Data by @HelemLebanon

:flecha_a_la_derecha: Swipe to learn more

— Syria Direct (@SyriaDirect) February 1, 2023

Loujain has been attacked several times in recent years. “On one occasion, thugs broke into our house, stole our things and beat us up,” she said, showing a photo on her phone of her battered face. She has also been stabbed twice while walking on the street. “I have no residency or ID to go and complain—maybe they will detain me because I have no residency,” she said.

In a more subtle way, she faces disapproving looks from other people. “I don’t want to change something about myself because of what people think, the important thing is that I’m comfortable with myself, but when people look at me as if I was wrong, it hurts,” she said.

As a veiled woman, Maram has not been targeted for her identity, but her girlfriend has. “She has short hair, it shows she is a lesbian. People on the street shouted at her, ‘Are you a man or a woman?’ She doesn’t leave the house much,” Maram said.

She has, however, faced sexual harassment at her job. “After three weeks of my boss harassing me verbally and touching me. I tried to make him understand that I won’t accept his behavior,” Maram said. Like 83 percent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon, she does not have legal residency, which puts her in a vulnerable position to defend her rights.

For Danny, safety and invisibility go hand in hand.“Everyone here, neighbors, landlord, work they don’t know I am trans, I am just Danny,” he explained. Only sometimes, like when he goes with his friends to the beach and he keeps his T-shirt on, does he fear being discovered.

“Sometimes I feel embarrassed that they don’t know about me, but they won’t understand. The past stays in Syria. I came to Lebanon as Danny, and I am happy because that Danny that I was dreaming of, I can see in front of me,” he said. His only regret is that his parents died before he transitioned. “They’d have loved to see me here, as Danny. They didn’t see me like I am.”

Most of Danny’s friends are straight and cisgender, and he distances himself from other LGBTQ+ people. He says others in the community once threatened to out him as trans, so he feels safer staying away, even if he has to conceal his identity.

But Maram and Loujain, estranged from their blood relatives, have found a family among other LGBTQ+ people.

While some members of the community find solace in Beirut’s LGBTQ+friendly bars and nightclubs, Maram and Loujain, unable to afford even the transportation costs to get there, have created safe spaces among their small circle of friends’ houses. “I am happy with the people that are part of my life, but the society outside the house is not safe,” Maram said.

Loujain has a video on her phone, taken at the photo exhibit organized by the 1MORECUP media organization this past December where bisexual, lesbian and trans women who are survivors of sexual and gender-based violence told their stories.

She and her best friend, a Lebanese trans woman, seem elated as they walk through the gallery and see their portraits on the wall. It is a space that, for a moment, feels as safe as home. Some of those photographed did not show their faces, but Loujain did.

“Of course, I showed my face openly,” she said. “What am I going to fear? What more can they do?

Maram, Loujain and Danny have found some space to breathe in Lebanon, but feel trapped. All have applied for resettlement through UNHCR, and are waiting for a response.

“I have hope that we will leave. I wish we could get married once we go to America—we’ll see,” Maram said.

The dream is anywhere they can be themselves beyond their front door.

“I don’t care which country we get resettled in, the important thing is that I feel like a human being,” Loujain said.

*Maram, Danny and Louay are pseudonyms used due to security concerns. Certain identifying details have also been withheld.