Deir e-Zor teacher: After Islamic State, ‘enormous effort’ needed to counter extreme ideology

Dozens of schools reopened in the formerly Islamic State-held eastern […]

19 March 2018

Dozens of schools reopened in the formerly Islamic State-held eastern countryside of Deir e-Zor over the past month, giving more than 14,000 elementary and middle school students access to basic education after three and a half years of IS dominance.

The Islamic State captured Deir e-Zor in summer 2014, but largely lost control of the province in fall 2017 after separate offensives by the Syrian government and the United States-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Today, the SDF controls most of Deir e-Zor’s eastern countryside, where teachers such as Abd al-Karim al-Madani are working to reintegrate young local children into public schools and make up for lost time.

“We are trying to prepare them for next year,” al-Madani tells Syria Direct’s Layla al-Ahmad. In addition to teaching Arabic at a handful of schools in Deir e-Zor, al-Madani is also a member of the Deir e-Zor Civil Council and Education Committee. The students, whose ages range from 6-14, are placed into classes according to their level. Older students are to be integrated next year, he says.

While the teachers mainly focus on getting the students up to speed with basic reading and math skills, al-Madani says they also find themselves in an unfamiliar role: countering radical Islamist ideas that children internalized during IS control of the province.

“Eliminating these ‘dark thoughts’ is a very difficult task that requires an enormous effort,” says al-Madani.

“These students were exposed to IS publications and speeches day and night.”

Q: What is the state of the schools in eastern Deir e-Zor province?

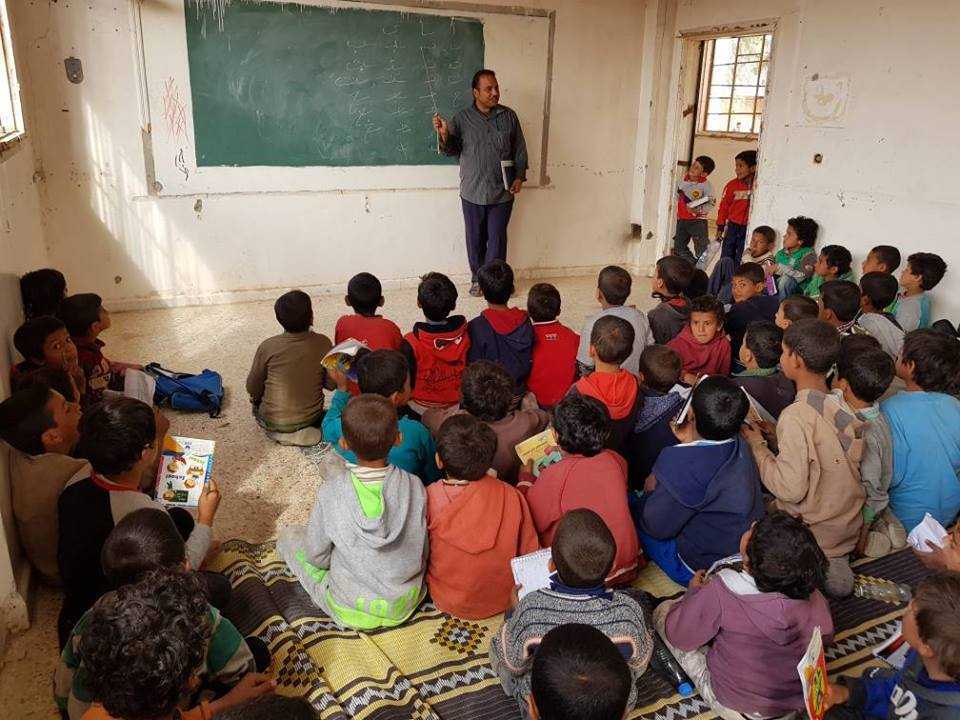

Most local schools are out of service. For example, in our area there are 70 schools but only 37 have reopened. Many schools were bombed, used as military bases by the Islamic State or looted and robbed of their furniture. Even the doors and windows are gone. All that is left in the classrooms are worn-down walls and cracked blackboards.

In some schools, students sit on the floor because of this destruction and robbery. The schools lack basic facilities, and we are having problems with drinking water and toilets.

Teachers are not being paid yet. The president of the Deir e-Zor Civil Council, Ghazan Youssef, and the council’s education representative, Kamal al-Moussa, recently met with an international delegation from the [United States-led, anti-IS] coalition to discuss this matter.

Q: What teaching strategies and curriculum are you using in these recently reopened schools?

This year is a transitional year for the students, so we are working to eradicate illiteracy and get rid of dark thoughts [Ed.: Islamic State ideology]. Students have been cut off from [regular] schools for four years. They need to be reintegrated into the educational system.

We start with the basics—ABC and one plus one—in addition to some physical and leisure activities.

In the future, we will be using the Syrian government curriculum, with the exception of the ‘national education’ subject. [Ed.: National education is a pro-government curriculum that teaches the fundamentals of the Arab Socialist Baath Party and Arab nationalism.]

Q: What was education like in Deir e-Zor under the Islamic State? Did you continue to work as a teacher at the time?

I taught for eight years while the government was in control, from 2005 until 2014, when IS entered Deir e-Zor.

Before IS came, the educational process worked somewhat well. The government paid teachers, provided furniture and supervised the schools. Even during the revolution, there were no major difficulties, and our facilities were in good shape.

When IS came, it put an end to all traditional education. They established 10 schools around the area [east Deir e-Zor countryside], usually using the houses of civilians. Most families wouldn’t send their children to the IS schools, for fear of having them exposed to the organization’s radical ideology.

IS imposed its own curriculum, based on reading, writing and speaking in addition to memorizing Surahs of the Quran, and screened their videos in those schools.

During those days, I worked odd jobs outside my profession as a teacher. I made ice cream, sold gas and repaired and sold cell phones.

Q: Now that you are a teacher once more, what are you doing to counter what you described as the “dark thoughts” IS left behind in the minds of students?

Eliminating these ‘dark thoughts’ is a very difficult task that requires an enormous effort, especially since there are no psychotherapists in the area.

I have one 10-year-old student who brought a knife with him to school one day and started teaching his classmates how to slaughter another person just as he had seen it in one of the [IS] publications. We reported the incident, and his guardian was summoned. One of my colleagues, a graduate from the Faculty of Education, talked to the student about the issue.

Another student opposed the idea of the mixed-gender classes in our schools. He had learned in the mosque that this was wrong. He was about 12 years old.

We focus on eradicating illiteracy, and try to correct any [IS] ideas that the students might display during class. We also teach them about the real Islam, which is all about forgiveness, justice and equality. We tell them that Islam is our religion from the time of our fathers and grandfathers, and that IS is a terrorist group that has nothing to do with Islam.

Ridding the students of radical and dark thoughts is no easy task. These students were exposed to IS publications and speeches day and night.

We call on international humanitarian organizations to help us and support education in Deir e-Zor’s eastern countryside.

Q: What is the role of students’ parents in this process?

All of the parents—most of whom only possess basic education themselves—are very happy that the schools have reopened, and they are excited to send their children back to school.

They have been extremely supportive. Some helped clean the schools, while others provided water or donated boxes of chalk and bookbags. Everyone is helping out on an individual level, but altogether this is making such a big difference for us and the students.