Disillusioned by UN inertia, Syrians raise funds for parched desert camp

In May, UNICEF abruptly reduced the water supply to Rukban camp, in Syria’s southern desert. Feeling abandoned by the international community, local groups and Syrian aid organizations are stepping in to relieve the parched camp.

25 August 2022

ERBIL — Water has always been a lifeline for roughly 10,000 Syrians stranded in Rukban, an informal camp for displaced persons located deep in Syria’s southern desert, along the border with Jordan. The settlement could not survive without water pumped from Jordan to the camp through two delivery points inside Syria.

But at the end of May, without warning and to residents’ horror, the flow of water to the camp was abruptly reduced.

At the delivery points, taps started running for only one to two hours a day, driving some residents to take desperate measures to collect some precious drops. “We started going to the water pipes at midnight to get a spot in line until the water came, at eleven in the morning,” Hussein, a camp resident speaking under a pseudonym for safety reasons, told Syria Direct.

“People started fighting over water,” Hussein added. One day, “a man started quarreling with others who were waiting for their turn, and fired a pistol in the air. The clash was ended by giving the man some water: he hadn’t received any for several days.”

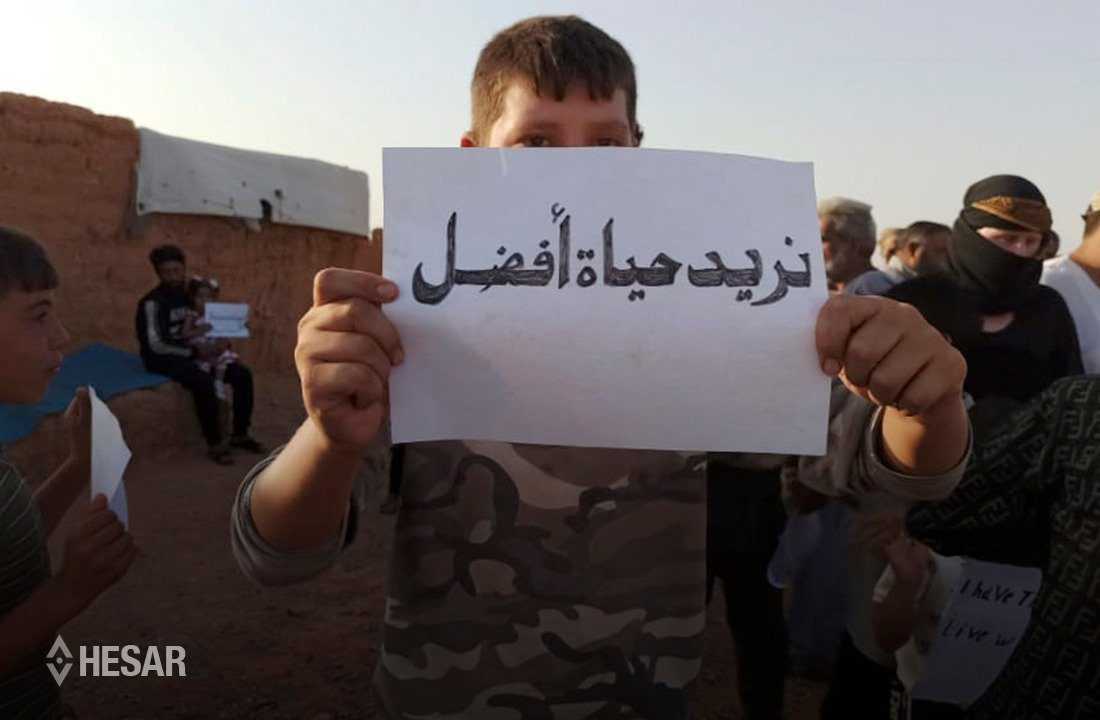

Local activists staged protests and launched a social media campaign begging UNICEF, the United Nations agency in charge of supplying water to the camp, to restore the water supply to its pre-May levels. They warned of a humanitarian disaster, in view of the extreme conditions faced by Rukban residents in the desert during the summer months. In early August, the Turkey-based Syrian National Coalition—Syria’s largest coalition of opposition groups—called on the United States, UN and Jordan to help the camp due to the water crisis.

The besieged people in #Rukbanـcamp organized protests, calling on the international and local parties to rescue more than 7000 besieged by the regime forces and Russia, suffering from thirst and lack of food in the desert near the Iraqi-Jordanian border.#انقذوا_مخيم_الركبان pic.twitter.com/CcVt0zPFEB

— Hesar (@hesar_net) August 5, 2022

Camp residents regularly stage sit-ins calling on humanitarian agencies to improve their living conditions, 5/8/2022 (Hesar)

These requests were met with deafening silence. On June 1, a UNICEF spokesperson confirmed to Syria Direct that there had been an “adjustment” in the water supply to reflect a decrease in the Rukban’s population in recent months. Earlier this month, UNICEF said there was “no update” to the water situation.

At the beginning of August, more than two months into the crisis, camp residents’ protests at last elicited a response, but not from the UN agency. Syrian organizations based in Turkey stepped in to truck in additional water from nearby wells, and the water supply is now back to an acceptable level, residents say. Still, the latest Rukban water crisis has highlighted and entrenched long-held distrust of international aid organizations.

A Syrian response

At the beginning of August, Molham Volunteer Team—a Turkey-based charity mostly active in opposition-controlled northwestern Syria—launched a relief campaign under the slogan “Save the Rukban Camp.” In coordination with the Rukban Local Council, one of several bodies claiming to represent Rukban’s residents, Molham purchased smuggled fuel in order to pump water from a well in the desert and one of the two UNICEF-supported delivery points and truck it back to the camp.

Every day, “300 liters of drinking water and 300 liters of water for other uses are supplied to 60 families,” according to Faisal al-Aswad, Molham’s Emergency Response Coordinator. In all, 200 Rukban families receive water twice per week. The charity, which has been supporting the camp sporadically since 2015, also supplies bread to some of its most vulnerable residents.

Another Turkey-based Syrian organization, the Emergency Response Team, also stepped in to cover the cost of bringing water from the same well to complement Molham’s efforts. “Every day we manage to bring in five trucks, each carrying 16,800 liters (16.8 cubic meters) of water,” Dulama Ali, a team leader in the Emergency Response Team, told Syria Direct.

“The idea behind these projects is to transfer water from wells in the desert to lower the consumption of drinking water pumped from Jordan,” Muhammad Ahmad Derbas al-Khalidi, the head of the Local Council—one of several local groups that claims to represent the camp residents—told Syria Direct.

Until August, Rukban received water from UNICEF alone, via two water pumping stations in Jordan. Pipes running out of each station carry water across the border to two delivery areas, locally known as the “eastern” and “western” collection points. There, residents and local water vendors fill barrels they transport to Rukban by donkey carts.

The two new initiatives complement this system with water pumped from Daqqaqa, a well located around 10 kilometers away from the camp. It is one of several wells dug in the area prior to the war, which remained unused for years due to the high cost of extracting and trucking the water. Unlike water supplied by UNICEF, the desert’s groundwater is brackish and unsuitable for human consumption—although it can be used for washing and livestock.

A third actor also contributed to these efforts: the US-led anti-Islamic State (IS) coalition, which operates in the area surrounding the camp in partnership with a local armed group, Maghawir al-Thawra (MAT). The coalition provided a new generator for the Daqqaqa well and recently rehabilitated another well, al-Khafiya, located 50 kilometers north of the camp.

“The well repair was part of the continued partnership between [the coalition] and our [MAT] partners to ensure the lasting defeat of ISIS, including through stabilization efforts,” a spokesperson from US Central Command told Syria Direct. Although the al-Khafiya well is intended for use by MAT, which operates a military outpost nearby, a MAT spokesperson told Syria Direct it would “alleviate” the water crisis, as “Bedouins in the area can benefit from it.”

Feeling abandoned

Since the camp’s establishment in 2014, when tens of thousands of Syrians fleeing war and persecution by the Syrian regime flocked towards the Jordanian border to seek refuge, Rukban has come to epitomize the UN’s failure to provide humanitarian support to all Syrians in need in different areas of control.

Rukban hosts former opposition fighters and their families and is besieged by the Syrian regime, which hinders access to the camp from the Syrian side. And since 2018, Jordan has also refused to allow aid, with the exception of water, into Rukban from its territory, saying the camp is not its humanitarian responsibility. As a result, no UN aid convoy has reached Rukban since 2019.

“We are used to living in a state of perpetual crisis, we are constantly besieged,” Mahmoud Qasem al-Hamili, a member of the Civil Administration, another group in Rukban that claims to represent the camp’s population, told Syria Direct. “But [the water crisis] really choked us.”

The only assistance the UN still manages to provide to Rukban is the UNICEF water line, but even this has now been slashed by at least 25 percent—from around 400 cubic meters to 300 cubic meters per day according to al-Hamili, an estimate that could not be independently verified.

UNICEF told Syria Direct the water supply has been “adjusted based on the latest available population estimates, with the aim to maintain the standard level of water provided per person in the community.” The basis on which this decision was made is unclear, however, since aid agencies have no physical access to the camp and no population census has been carried out in years. Local media activists usually refer to a figure of 7,000-10,000 people still living in Rukban, down from a peak of 85,000 in 2017.

“We are 8,000-10,000 people here and we have water for two hours a day, how do they expect this to be enough?” Hussein said.

UNICEF declined to confirm the exact volume of water pumped to the camp but said it was currently providing “65 liters of water per person per day,” which Rukban residents use not only for drinking and washing, but also to maintain their mud houses and water livestock, fruit trees and small vegetable gardens they rely on due to the complete lack of food aid.

A communication gap

On June 1st, UNICEF told Syria Direct that following “consultations with the community”, the water supply had been slightly increased since the initial cut in May. But none of the residents who spoke to Syria Direct were aware of these consultations.

“UNICEF never ever communicates with us,” al-Hamili of the Civil Administration said. “We usually communicate with OCHA [the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs] or directly with UNICEF’s partner, the company that manages the water supply.” Al-Khalidi, the head of the competing Local Council, also said he has had no contact with UNICEF or any other UN agency since the start of the crisis.

Children in Rukban hold a poster addressed to Tanya Chapuisat, the country representative of UNICEF in Jordan, August 2022 (Rukban Camp residents)

Disillusioned and frustrated, some residents accuse the UN agency of playing into the regime’s strategy to starve out the camp.

“From my point of view, the UN and Jordan are complicit with the criminal Syrian regime,” Hussein said, “and they are helping drive us out of the camp.” Al-Khalidi felt similarly: “This is pressure, pressure to push us to leave the camp,” he said.

Throughout its recent history, Rukban has been almost exclusively supported by private donors and Syrian organizations, who send money to the camp through trusted intermediaries. Some camp residents question why these groups manage to support them remotely, while the UN and international NGOs have so far proved unable to do the same despite their extensive means.

“The last donors’ conference [the Brussels VI conference held in May 2022] raised more than $6 billion for refugees both inside and outside Syria,” al-Khalidi added indignantly. “But they did not allocate a single cent to Rukban or its people.” In fact, pledges from the Brussels VI conference could indirectly support Rukban through funds provided to UNICEF.

[irp posts=”39285″ name=”In al-Rukban camp, humanitarian inaction opens avenues for aid diversion”]Large international organizations are extremely unlikely to operate in Rukban: the financial, legal and reputational risks they face are simply too high. Unlike local organizations, who are mostly funded by private donors and the Syrian diaspora, international organizations rely on funding from large institutional donors who impose strict transparency rules.

Without physical access to Rukban, NGOs have virtually no means to track the money spent. They also have a limited choice of local partners, with at least two local bodies claiming to represent the camp’s population, in a context rife with accusations of corruption and aid diversion. The fact that goods are brought to the camp by smugglers adds a layer of opacity to any potential aid operation.

Stranded in a dusty camp for years, many people in Rukban no longer expect anything from the international community. “This situation is shameful and disgraceful,” al-Aswad said, “because they haven’t been able to end the suffering of the camp and help it.”

So day after day, from one crisis to the next, Rukban clings to existence, hanging on to tenuous threads: smuggled flour, donations from abroad and brackish drops of water extracted from the desert.