From one of Syria’s most-bombed cities, street art sends the world a message: ‘There is always something beautiful, despite all the pain’

Some days, when he has a good idea, when the […]

16 August 2016

Some days, when he has a good idea, when the pace of the bombing lessens and when he can find paint and brushes, Abu Malek a-Shami sets off looking for a clean space amidst the rubble of one of Syria’s most-bombed cities.

The falling roofs of bombed buildings are his canvases, “so they can be seen from the ground and from above,” he tells Syria Direct’s Hussam Eddin. It is “a message to the world that we can make something beautiful out of the destruction and ruin of war.”

Abu Malek a-Shami is a street artist. His work ranges from small bits of graffiti to wall-sized murals. A-Shami’s 32 murals are splashes of color in a lifeless landscape. His art draws on his experience as a fighter, artist and current resident of Darayya.

The 22-year-old activist-turned-fighter came to the southwest suburb of the capital from Damascus three years ago to fight with the Free Syrian Army. In 2015, he started painting.

“At first, I was afraid of how people would react to the paintings on the walls of their demolished homes,” a-Shami says. “It’s something of an emotional subject. People here have lost nearly everything, and they have a very strong connection to their homes.”

After the first painting on Darayya’s walls, “I noticed the amount of happiness and optimism it spread on the faces of the blockaded people,” he says. “It made me feel the value of my work, its positive impact.”

Darayya was one of the first Syrian cities to rise up against the regime in 2011. Protestors famously offered roses and bottled water to soldiers stationed in the city. Symbolically important to the opposition, Darayya is strategically important to the regime, located near major military installations southwest of Damascus.

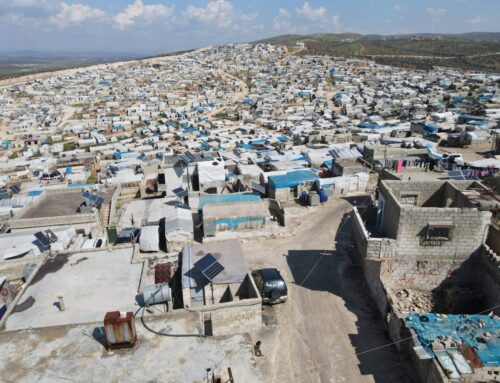

Regime forces encircled Darayya in 2012 and have blockaded it and attempted to take control since then. Under a rain of daily barrel bombings, residents spend their days underground in shelters, their homes reduced to rubble above their heads.

Some murals are elegies to fallen friends. Others touch on more universal themes. In one, furnishings painted on the wall of an abandoned, demolished house are a shadow of normal life and a message of permanence. In another, a young girl, standing on a mountain of military helmets and skulls, paints the word “hope.”

“It shows that there is always something beautiful waiting for us, despite all the pain that we’re experiencing,” he says.

Q: When did you start painting on the walls of Darayya? What inspired you?

In the revolution, I’m known by the name Abu Malek a-Shami. I’m 22 years old. I came to Darayya in early 2013 to fight with the Free Syrian Army [FSA] and to participate in its defense.

Before that, I participated in the peaceful civilian mobilization in the Kafr Sousa neighborhood of Damascus. I wrote signs and drew graffiti.

Ever since I was young, painting has been my hobby. I’ve made use of this talent to serve the cause [the revolution] that I’m working for.

When I first came to Darayya, I was a stranger to the people here. I didn’t have any relationships or friendships here. I started working with the FSA in the city. Months after the battle began, the pace of the clashes slowed down and we started to have spare time to go back to social life and peaceful work once more.

I went back to painting the walls of the base I spend my days in. I decorated it with paintings, wrote some phrases eliciting optimism or mourning one of my martyred friends.

One day the citizen journalist Majd Moadimani was at my base and he saw the paintings on the walls. He told me he was thinking of using this talent to decorate Darayya’s streets, which are filled with destruction. I liked the idea, and we agreed on a meeting to set the steps to begin working.

It was my suggestion to use the wrecked and leaning roofs, so they can be seen from the ground and from above, as a message to the world that we can make something beautiful out of the destruction and ruin of war.

At first, I was afraid of how people would react to the paintings on the walls of their demolished homes. It’s something of an emotional subject. People here have lost nearly everything, and they have a very strong connection to their homes.

When I first started, I intentionally limited myself to the walls that weren’t visible. But when I posted the first mural [online], it was received well and resonated inside and outside Darayya.

People started asking who was drawing these murals. They started giving ideas, tips and good locations. They gave critiques for the paintings to be more beautiful and complete. People’s advice and comments gave me a lot of motivation to keep going, to make new paintings.

A number of famous painters in Syria and the Arab nation have communicated with me, given me advice and good ideas to paint. They’ve provided me with some technical advice and professional touches for painting graffiti.

Q: What makes you keep painting, after four years of war?

God gave me a good talent, and I believe that it is the duty of those with the ability to do everything possible to serve our cause.

After the first painting on Darayya’s walls, I noticed the amount of happiness and optimism it spread on the faces of the blockaded people. The first mural became a place to visit, to take commemorative photos. It made me feel the value of my work, its positive impact.

In one of the battles in 2015, I was wounded and couldn’t work for five months. It was a long time.

My partner, Majd, was killed shortly after I was wounded. In our last conversation, he told me that I needed to find somebody to help me, and to keep painting. He said that even if I didn’t find a helper, that the paintings have a huge positive impact. It seemed as though it was his last will.

The first mural I drew after my injury was in Majd’s memory. Majd was considered an icon in documenting the fall of barrel bombs in Syria.

I have full belief that this message should continue to be sent for as long as I am able.

Q: How many murals have you painted so far?

I have 32 murals scattered throughout Darayya. Some of them still have their colors and lines, others have lost much of their details due to the continuous bombardment of the city.

I completed 10 of them after recovering from my injury.

Q: What is your process? What tools do you use?

First, we determine an idea for the mural, and come up with an initial design. I discuss it with the people around me, then draw a small model on paper.

Then I search for a wall that might suit the painting. I clean off the dust and debris, then draw with charcoal or pencil, so that I can correct any mistakes.

When I find the drawing is right and suitable, I paint it using oil paints mixed with benzene [gasoline] to preserve the colors and help it resist the environmental and climate conditions and last as long as possible.

Each mural takes between two hours and two or more days. It depends on the size of the painting and the complexity of its colors.

Q: What difficulties might a painter face in a blockaded area?

Before the revolution, painting on the walls, or painting in this way—which carries a political or social message—was a crime I could spend the rest of my life in regime prison for.

The difficulties come from the reality of the siege itself. You don’t always have tools like paints or brushes. You’re forced to search for alternatives that are less effective.

I’m not completely free to paint. I have other responsibilities in the city, and there are no academic experiences through which to develop my work, to give me enough technical experience to reach professionalism.

Q: Can you choose some of your paintings and explain them?

The painting I’ve called “Hope” was the first to really resonate. It shows a young girl standing on a hill of [skulls wearing] military helmets, and she’s writing the word “hope.” It shows that there is always something beautiful waiting for us, despite all the pain that we’re experiencing.

The painting that spread a lot outside Syria was the furnishings of an empty, dilapidated house, the walls a metaphor for connection to the homeland and the house, even if it were destroyed.

The most famous painting was a message to the fighters. It shows a soldier holding his rifle, sitting in front of a young girl who is instructing him. This painting can be summed up in three ideas: be merciful and use your heart, use your mind and don’t be a pawn.