Humanitarian responses to the coronavirus bring the UAE and Syria publicly closer

Since Syria’s membership in the Arab League was suspended in 2011, the phone call marks the first publicized contact between an Arab leader and Assad since 2011.

15 April 2020

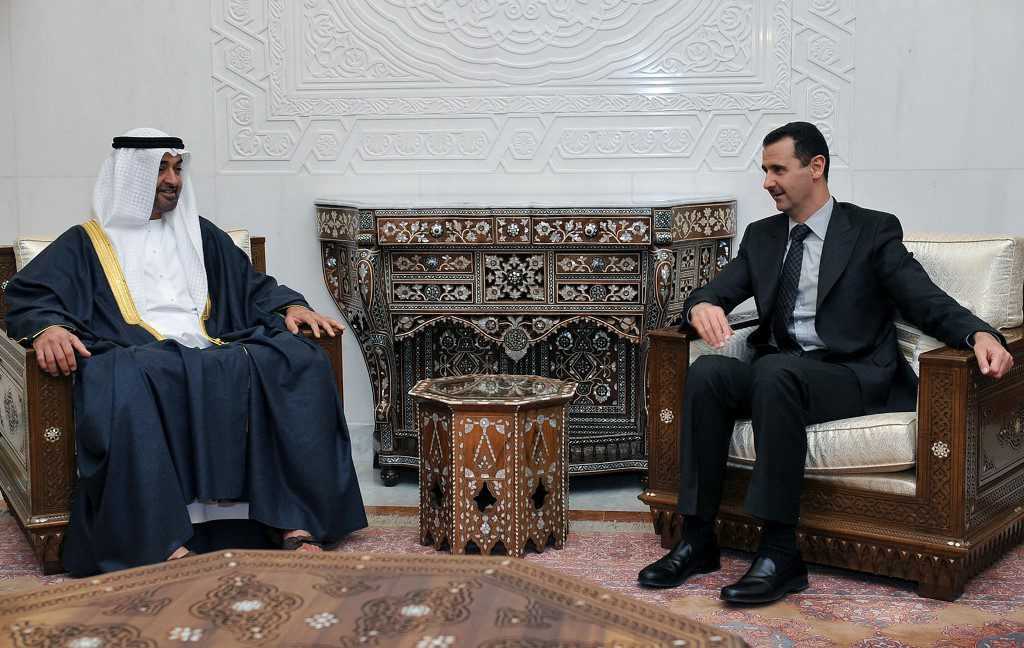

Bashar al-Assad meets with Abu Dhabi's Crown Prince Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed in Damascus, 13/1/2009 (AFP)

AMMAN — On March 27, Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Armed Forces, spoke on the phone with Bashar al-Assad about the spread of coronavirus throughout the region.

According to the state-run Emirates News Agency, Zayed spoke about “rising above political issues during this common challenge that we are all facing.” Syrian state news agency SANA also noted that Zayed had stressed that Syria would not be alone in these critical circumstances. In response, Assad “praised the humanitarian position of the UAE and welcomed his [Zayed’s] cooperation.”

Since Syria’s membership in the Arab League was suspended in 2011, the phone call marks the first publicized contact between an Arab leader and Assad since 2011, with the notable exception of Sudan’s now-deposed president, Omar al-Bashir, who visited Syria in 2018.

Gradual shifts in Emirati policy

Over the past two years, the UAE has made small overtures toward the Syrian government, demonstrating a change in its stance toward the Assad regime as compared to the one it adopted in 2011.

According to a special report in The Guardian, the UAE had floated the idea of normalizing relations with Syria as early as 2016, but the proposal was shot down by the incoming Trump administration soon after.

In April 2018, the UAE’s Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Anwar Gargash, reflected on his country’s relationship with Syria, saying that, “a few years ago we had a choice — to support Bashar Assad or the opposition, which was joined by jihadists and even many terrorist elements, and we chose to be somewhere between.”

By December 2018, the UAE had reopened its embassy in Damascus with Gargash tweeting that “an Arab role in Syria has become even more necessary to face the regional expansionism of Iran and Turkey”. A day later, Bahrain followed suit and added a statement that its diplomatic mission had been operating in Syria “without interruption.”

Although the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries formed the backbone of regional opposition to the Assad regime in 2011, the UAE had always been more reserved than Saudi Arabia and Qatar in its efforts.

“The UAE effectively sat out the armed conflict in Syria, because at the end of the day, their preeminent regional occupation is militancy,” Michael Wahid Hanna, a senior fellow specializing in international security and Arab politics at The Century Foundation, told Syria Direct. “They were never going to join in the effort to overthrow Assad in light of the spillover threats posed by rebel forces and the core militant elements that animated the opposition as the war dragged on.”

Instead, the UAE is understood to have played a more humanitarian role during the early stages of the conflict while also serving as a financial and logistical hub for the Syrian opposition.

Although the UAE has drifted away from the policy of its GCC neighbors in recent years, a total normalization of relations with Syria remains unlikely in the near future, according to Hanna. “All these moves are still pretty hesitant and it’s unlikely that UAE is going to make a massive shift on Syria without the cover of other regional actors joining in.”

Commercial interests bridge the gaps between the UAE and Syria

While political relations remain undefined and subject to change, important commercial interests have been an enduring feature of the relationship between the UAE and Syria over the past two decades.

Prior to 2011, the UAE made a number of significant investments in Syria after the latter began its policy of economic liberalization in the early 2000s. These investments were centered around the burgeoning real-estate sector, including hotels, shopping malls, office space, and apartments, chiefly located in Damascus and Syria’s coastal city of Latakia. However, Emirati investors also held stakes in Syria’s developing private banking sector and the growing tourism sector.

The rush of investments was by no means unique to the UAE. It is estimated that Gulf-based companies invested upwards of $20 billion from the early 2000s until the beginning of the uprisings in 2011.

As Rashad Al-Kattan, a political and security risk analyst and a fellow with the Centre for Syrian Studies (CSS) at the University of St. Andrews, noted in a research paper, “Gulf-based conglomerates, especially from the UAE, Qatar and Kuwait, flocked to Syria with tremendous amounts of cash to participate in the booming real estate development, tourism, banking and financial services.”

Following the outbreak of protests in 2011, many of these investments came to a temporary halt—especially after the UAE advised its citizens to leave Syria in November 2011 and closed its embassy in March 2012.

Nevertheless, relations between the two countries did not completely break down. The UAE allowed the Syrian embassy to operate in Abu Dhabi and even facilitated the entry of Assad’s mother, Anisa, and his sister, Bushra, to the country.

Importantly, key regime-linked businessmen such as Samer Foz and Rami Makhlouf continue to operate their businesses, especially through a vast network of shell companies in Dubai’s Jebel Ali Free Zone to evade taxes and international sanctions. Even a Dubai-based company, Yona Star, was sanctioned by the US in 2016 for acting as a shipping agent for sections of the Syrian military.

Preparing for the long-awaited ‘reconstruction’

For many years, the UAE has attempted to position itself in such a way as to reap the possible benefits of Syrian reconstruction.

In 2013, for example, the UAE-based logistics company Gulftainer, won a concession to build and operate the Port of Tripoli in Lebanon, investing $60 million in infrastructure upgrades. The decision to develop the port in Tripoli—located less than 100km from the Syrian city of Hama—was in part informed by discussions surrounding Syrian reconstruction. Antoine Amatoury, Gulftainer’s chairman in Lebanon, said that “Tripoli is an important launch platform for the reconstruction of Syria and Iraq, and this is what will drive us forward to face those who want to hinder the process.”

More recently, in January 2019, Dubai Ports World (DPW), one of the UAE’s largest companies and one of the biggest global ports operators, established a 2,500km transport corridor from Jebel Ali Port in Dubai to the Jaber-Naseeb crossing between Jordan and Syria. DPW said that its first convoy of three Dubai-registered trucks made the journey in six days, as opposed to 24 days when the border was closed. The transport corridor aims to increase trade between the UAE, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and Saudi Arabia.

Aside from Emirati companies investing in Syria, Syrian regime-linked businessmen have also courted the Emirates for possible capital assistance. In January 2019, Abu Dhabi hosted a delegation of Syrian businessmen from a wide range of economic and trade sectors to discuss future investments. Headed by Muhammad Hamsho, the delegation also included businessmen close to the regime such as Samer Debs, Wassim Qattan, and Fares Shehabi.

However, with deepening US sanctions on Syria, further commercial investments remain unlikely in the near future. Emirati companies fear being shut out from the US financial system if caught dealing with the Syrian government. As Joseph Daher, a scholar of political economy at Lausanne University noted, “UAE investments in Syria, especially in reconstruction schemes, have so far gone no further than being announced and are therefore not expected to materialise soon.”

Humanitarian efforts intersect with foreign policy ambitions

The UAE brands itself as the leading humanitarian provider in the Middle East. In Dubai, it houses the International Humanitarian City (IHC), which hosts nine UN agencies and more than 85 NGOs and provides aid to numerous conflict areas across the world.

However, humanitarian aid distribution largely consists of complex logistical operations, whereby private logistics firms have become increasingly more important to humanitarian organizations. By centralizing logistical operations for humanitarian purposes in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, the UAE has solidified itself as a leading humanitarian hub, benefitting many of the Emirati-based companies involved in logistics and trade.

By focusing specifically on the coronavirus during Zayed’s call with Assad, the UAE can pursue a dual-strategy of improving relations with the Syrian government while demonstrating its commitment to global humanitarian work.

In fact, the UAE has already pursued a similar strategy toward Iran. In early March, the UAE sent two aid aircrafts loaded with 32 metric tons of supplies to Iran to help the country battle with its outbreak of the virus.

Although Abu Dhabi has traditionally sought to stem Iran’s regional aspirations, in the past year, there are strong indications that it is trying to de-escalate regional tensions. Following the attack on four tankers in the Gulf of Oman in May 2019, the UAE made important political overtures to Iran in an attempt to improve relations between the two countries.

“The Iran-UAE relationship has historically been led by trade and economics. Alliances and conflicts in the region have impacted their relations, but there is too much at stake for both sides for a total shutting down of relations,” Arash Azizi, a PhD candidate in History at New York University, told Syria Direct. “As such, the UAE’s assistance to Iran and Syria is definitely part of its foreign policy moves.”

By relying on humanitarian justifications, the UAE can also pursue its independent foreign policy goals and deflect any potential opposition from allies such as Saudi Arabia and the United States that are more hostile toward Iran.

“The UAE has sided with the Saudis against Iran, but it has never gone all the way,” Azizi explained. “It wants to maintain its status as a humanitarian hub, which they have done successfully in the past two months. Its assistance to Iran was officially praised by Tehran and the WHO applauded its overall role in helping neighboring states.”

Although the same direct form of assistance has not been promised to Syria, the decision to reach out to Syria under the current circumstances signals the UAE’s willingness to operate independently from its regional and international allies.

Cautious steps toward regional realignment?

Although there are clear political and economic motives for the UAE’s decision to engage with Iran and Syria in recent months, it is still too early to expect broader regional realignments.

According to Hanna, “the UAE is unlikely to make a total shift without some cover from Saudi Arabia.” When Abu Dhabi has acted independently, “it only did so when it believed it was pursuing vital interests, and Syria probably doesn’t fall into that category of importance now,” Hanna added.

Given the current open-ended geopolitical environment, it is unclear to what extent the UAE will prioritize relations with the Assad regime over other regional issues.

“MBZ’s [Mohamed bin Zayed] policy seems to be eventual reconciliation with Damascus and Tehran,” according to Azizi, adding that “in the short and medium-term, they are more worried about prospects of armed conflict in the region and will push for reconciliatory moves.”

There have also been reports that the UAE is exploiting the issue to aggravate Turkey and its military operations in northern Syria. According to one unnamed source, Zayed had been trying to get Assad to break a ceasefire with Turkish-backed fighters in Idlib.

Hanna, however, remained skeptical of such a conclusion. “There are multiple levels of rivalry and competition between the UAE and Turkey, so no one factor can be seen as wholly determinative.”

Speaking about the recent call between Zayed and Assad and its implications for Turkish regional ambitions, he told Syria Direct that “it has the added benefit from the UAE perspective of offering another avenue for competition [with Turkey], but it’s clearly not the main motivation.”

While the normalization of relations between the UAE and Syria is unlikely to happen anytime soon, new geopolitical fault lines may emerge from the wreckage of the coronavirus. The UAE’s humanitarian infrastructure, however, will continue to provide Abu Dhabi with an important tool through which it can try to reshape the regional landscape for years to come.