Idlib’s education director tours the province to find out: Why are so many children dropping out?

In rebel-controlled Idlib province, school enrollment is plummeting. Idlib’s Education […]

25 May 2017

In rebel-controlled Idlib province, school enrollment is plummeting.

Idlib’s Education Directorate last counted as little as 46 percent of students still attending classes in the provincial capital, according to pro-opposition news outlet SMART News.

So in January, Khaled a-Rahmoun, a 54-year-old former geography teacher who now works as director of elementary education in Idlib’s opposition-run government, set out on a road trip. He travelled across Idlib province, interviewing hundreds of school dropouts and their families to find out why so many children weren’t showing up to class.

What a-Rahmoun found were “broken” families, as he describes them—children and parents battered by years of war, displacement and economic hardship.

Dozens of interviewees were among the busloads of people who recently arrived from towns and cities across the country that agreed to ceasefire and evacuation deals with the Syrian government.

Why aren’t they in school?

A “huge number” were teenage girls, pressured to marry and take on household duties to “lighten the burden” on their cash-strapped families.

Others were young boys who “work in the souq like grown adults,” to support their parents, a-Rahmoun tells Syria Direct’s Alaa Nassar.

Q: What were the main reasons you found for nonattendance among students across Idlib province?

From the sample that I interviewed, I found that 74 percent of middle schoolers who didn’t go to school said they were absent because of difficulties studying. For high schoolers, 77 percent of dropouts said they left in order to find work. In elementary school, 74 percent of absentees said they couldn’t come to school because of broken families, or because their families were scattered.

There is also a huge rate of nonattendance for high school girls and even middle school girls due to early marriage. Parents’ main concern now has become “moving out the daughters,” so that they can get married, lighten the burden on their families and go live with a man who can protect her in case her father dies or gets arrested.

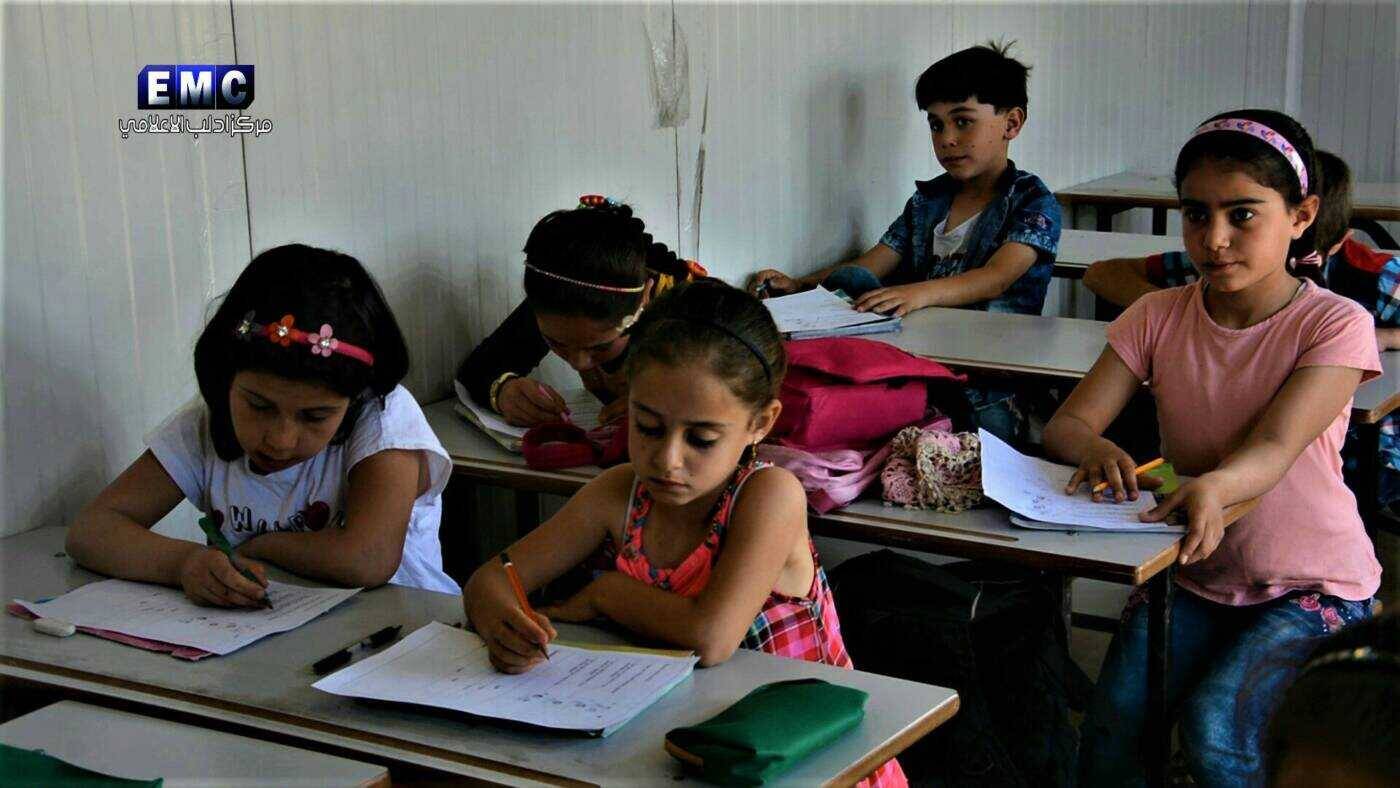

Idlib children last week. Photo courtesy of Idlib Media Center.

Girls are also pressured to stay home from school if one of her parents dies —especially the mother—in which case, she takes over the household responsibilities.

We also see students leave school for economic reasons and go work in the souq like grown adults. They gather scrap metal and sell gum and tissues to make ends meet for their families. Many of these students are children who were displaced from other areas [of Syria].

Q: What are you doing to slow down the dropout rate in Idlib province?

Our options are limited, considering how many new arrivals have come to Idlib [in recent months].

All students have been tested and placed [in classes according to their abilities and potential.] However, we know that displaced families [who recently arrived to Idlib] need about a month to settle in before they can even begin thinking about putting their children in schools.

As a result of forced displacement to Idlib, most of the families were dispersed. The absence of stability leads to children not going to schools, despite that fact that we try with each family we receive to convince the parents to send their children.

For example, I recently visited with parents from Darayya. [Ed.: Darayya is a former rebel stronghold in the southern suburbs of Damascus. After four years of siege, an August 2016 deal between the town’s rebel authorities and the regime provided for the evacuation of its remaining residents—some 8,000 people, both fighters and civilians—to rebel-held Idlib province.] They had three children at elementary school levels, and when we discussed sending his children back to school, the father started crying. It made me cry with him.

He told me that his children were at the top of their classes at their school in Darayya, but unfortunately they had to leave their home—he said he had nothing left. That’s the psychological state that his children will learn in, and there are families across Idlib province in the same situation.

This father didn’t even have any documents proving that his three children belonged to him, since all of his paperwork had burned along with his family ledger and other identity papers. [Ed.: In Syria and much of the Middle East, births, deaths, marriages, divorces and all issues pertaining to a family are catalogued and compiled in family ledgers, which are small booklets resembling passports].

He said: “Today, I’m embarrassed in front of my children. They ask me for food, and I can’t afford to feed them.”

Q: What are the consequences of the high dropout rate in Idlib?

It weakens the productivity of a dropout when he joins the workforce, since he isn’t prepared.

There is a cultural effect as well—we find huge numbers of dropouts becoming illiterate, especially those who did not finish their elementary studies.

Dropping out of school also makes someone vulnerable to destructive behaviors and moral indecency. They become tools for the destruction of society, and this is what the Assad regime does.

We also see a political effect, as [lack of primary education] lowers the social and political awareness among young people who become unable to follow and understand what is happening around them. It makes them easy prey to prejudice, and he can easily be seduced by the colonial ambitions of foreign nations, terrorist groups or war profiteers.