In earthquake-stricken Latakia, disappearing aid and no ‘alternative housing’ plan for the displaced

In Latakia, the Damascus-controlled province most impacted by the February 6 earthquake, “chaos” ruled the emergency response, amid concerns about long-term displacement in the absence of a plan for alternative housing.

21 February 2023

DAMASCUS — Abu Firas left his home in the Latakia countryside village of Istamo at dawn on February 6, heading for the local bakery to buy bread. As soon as he arrived, he felt the ground shake. He rushed back to his house, only to find the building completely destroyed, collapsed on top of its residents.

Abu Firas, a taxi driver, lived with his wife and four children on the third floor of a five-story building. The earthquake that struck five Syrian provinces and southern Turkey more than two weeks ago wiped it out completely. He lost three of his children, while his wife and youngest daughter survived.

Nearly 45,000 people were killed and tens of thousands injured in the February 6 earthquake in Turkey and Syria. In Syria, the toll was at least 3,891 people reportedly killed and 14,814 injured. And in areas controlled by the Damascus government, 1,414 deaths and 2,357 injuries were recorded, according to figures from the Syrian Ministry of Health.

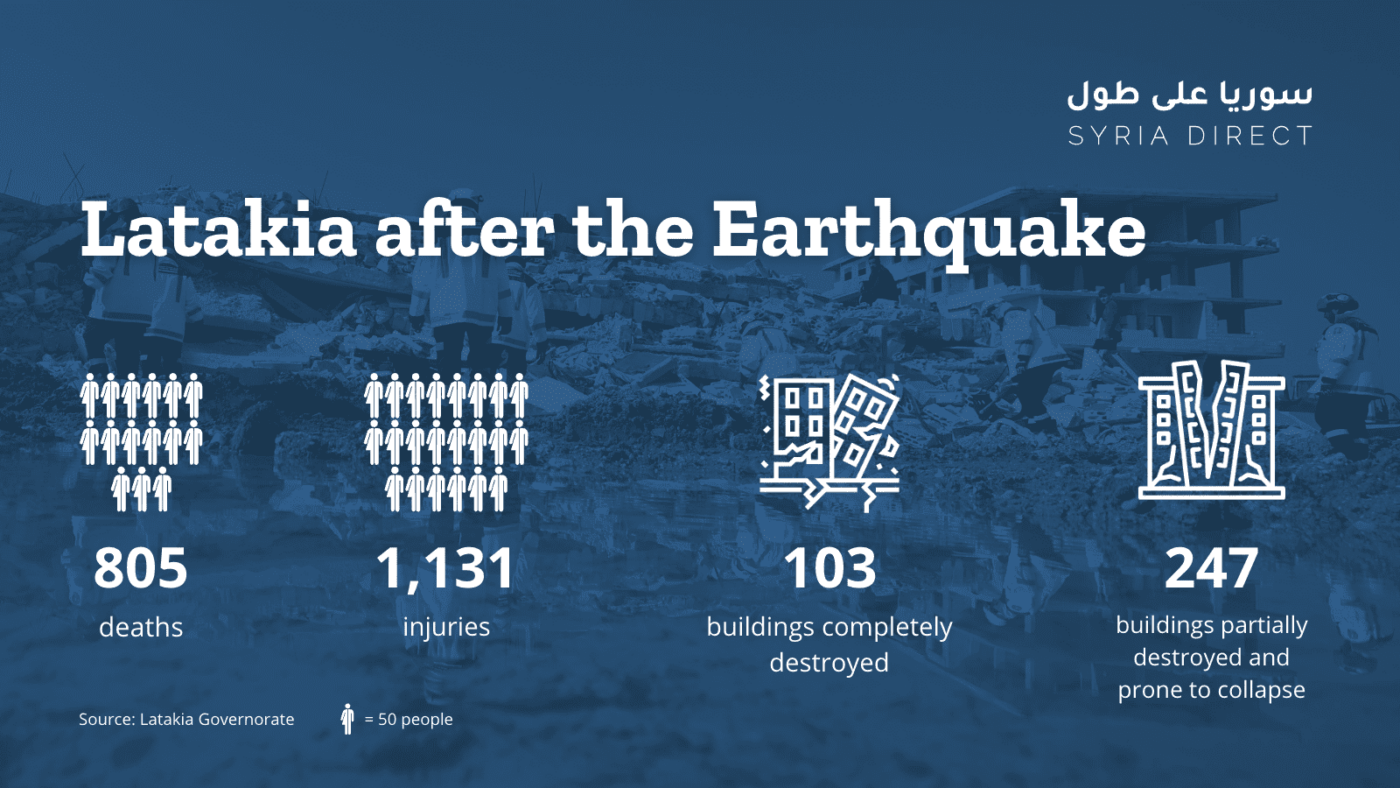

Infographic | Number of casualties and destroyed buildings in Latakia, Syria after the February 6, 2023 earthquake (Syria Direct, background photo: Karim Sahib/AFP)

Chaos and villages without aid

In the wake of the devastating earthquake, aid shipments from several countries arrived in areas controlled by the Damascus government. Previously licensed associations and individual initiatives also actively provided support and assistance to those impacted by the disaster.

As of Tuesday, some 194 planes carrying aid had arrived at airports in Aleppo, Latakia and Damascus, according to the local media outlet Athr Press. The planes, including 85 from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) alone, brought food, medical supplies and rescue teams.

A week after the earthquake, the Syrian government took measures to organize the delivery of earthquake aid through regional managers in the country’s provinces. They were to receive the aid and track its distribution to those entitled to it, in coordination with relief subcommittees under a primary relief committee in Damascus, headed by Minister of Local Administration Hussein Makhlouf.

But “chaos” dominated the early emergency response amid a “weak response from the Syrian government, lacking a clear action plan,” in the words of Latakia-based lawyer and civil activist Kamal Suleiman.

While civil society actors worked actively in the two days after the earthquake, “the reality on the ground was catastrophic,” Suleiman said. For some villages in the countryside of Latakia, the worst-affected province in Damascus-controlled areas, “aid did not reach them as needed,” he said.

The areas that saw the total destruction of some buildings were given “the priority in relief,” he said. The worst-hit areas included the 10th Project, a residential neighborhood northwest of Latakia city, al-Ramal al-Janubi, an impoverished neighborhood in the city’s south, and Jableh, a city on the coast 25 kilometers south of the provincial capital.

The response in these areas was “more urgent, because they are densely populated, unlike the remote villages, where the percentage of damage is less,” Suleiman said. Aid did not reach those villages because they are “remote, and there is no machinery, or fuel to power what machinery there is,” he added.

More than 142,000 people in Latakia province were impacted by the earthquake, which completely destroyed 103 buildings and partially destroyed 247, leaving them prone to collapse. The province also recorded 805 deaths and 1,131 injuries, according to statements made by Governor Amer Hilal on February 13.

Some 11,732 buildings throughout the province have been inspected by the Structural Safety Committees under the Latakia branch of the General Company for Engineering Studies, the state news agency SANA quoted the company’s director, Siraj Jadid, as saying.

In Istamo village, around 70 damaged buildings were evacuated, and 3,000 families were impacted—including that of Abu Firas. He took refuge with a relative in a neighboring village, because the shelter in Istamo was overcrowded with others displaced from their homes.

The Syria Trust for Development—a major NGO founded by First Lady Asma al-Assad—and the Ministry of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection, in coordination with the relief subcommittees, are supervising 226 shelters in Damascus-controlled areas established to receive around 298,000 people in the impacted areas.

Theft and corruption

After the earthquake, Malak, 45, evacuated her house in the al-Ramal al-Janubi neighborhood of Latakia city. It was sealed with red wax and declared “uninhabitable,” she told Syria Direct. She went to the Sports City shelter in Latakia.

There, she is struggling with the “arbitrary distribution of aid to the impacted people,” she said. She is not used to “life in the shelter, and the narrow space I occupy with my six children.” Malak said she has not been able to bathe, and fears that illnesses could spread and infect her children.

“The shelters in Latakia suffer from a lack of medical and therapeutic services, due to the [condition of] the health sector in general,” lawyer and activist Suleiman said. “A number of local associations and the [Syrian Arab] Red Crescent [SARC]” are supporting the health side of the response, alongside private “donors who provide some health services, instead of the state.”

Despite the volume of aid that has reached Syrian government areas, Abu Firas, whose house was completely destroyed, said he has not received any since he is not staying at the shelter. He also said machinery was delayed in reaching his village after the earthquake.

Samer, a civil activist who works on the relief team of a charity in Latakia, said “aid distribution in the shelters was arbitrary on the first and second day after the earthquake.” He described “some of the displaced families getting one meal a day, while others get more than three.”

Samer, who asked to be identified only by his first name, said “aid theft” also took place. “Some of the aid disappeared after it arrived at relief centers supervised by the Syria Trust for Development, SARC and the al-Areen Foundation,” he said.

To limit abuses, the Latakia City Council asked those displaced to official shelters to provide documentation last week proving that they were residents of destroyed or evacuated buildings.

The Latakia Provincial Council also met to “decide on a specific mechanism to hold some opportunists accountable,” Suleiman said. “There are people who were not affected by the disaster, whose homes were not impacted, but whose names were put down because of poverty and need.”

He also said “the mukhtar of a village in Jableh was dismissed, because he gave someone a document proving that he is a resident of the affected area, but he is not.”

No alternative housing on the horizon

Without a clear vision in place to provide alternative housing for those affected by the earthquake, Malak worries about her and her six children losing their home without a replacement, meaning an indefinite stay in the shelter.

Suleiman stressed the need to “provide alternative housing for the owners of destroyed or partially damaged homes that were evacuated due to damages,” especially in light of “the lack of a rapid response plan for restoration.”

Indefinite stays in shelters and the provision of services there is “problematic, exacerbating the crisis,” Suleiman said. He called for “a mechanism to secure alternative housing and repair the damaged residences through a grant from the state.” The central “government has the capacity to restore stability and secure alternative housing—it is not helpless, after major assistance has arrived,” he said. That, however, “requires seriousness and proper crisis management.”

But before reconstruction can begin, rubble must be removed, which is extremely difficult in terms of the cost of removing and disposing of it, economic researcher Younes al-Karim said. That process also “could include removing buildings damaged by the war, alongside those damaged by the earthquake, which means the reconstruction of the four main affected provinces, and part[s] of Damascus, Aleppo, Idlib and Raqqa [provinces],” he told Syria Direct.

In al-Karim’s view, the National Fund for the Rehabilitation of Disaster Areas, announced on the fourth day after the earthquake, will be “the nucleus to launch the reconstruction of Syria as a whole, according to the regime’s vision and strategy, without international intervention protecting the rights of citizens.” He also is concerned it could become “a tool to take possession of the homes of those opposed to it, under the pretext of the public good—that they were damaged by the earthquake.”

On an official level, Syrian Minister of Public Works and Housing Suhail Abdullatif called on the directors of construction companies and institutions, during a February 15 meeting, to immediately equip 300 prefabricated housing units available to them to be ready for delivery.

The National Microfinance Bank also launched a “Support Loan,” allocated for the restoration and rehabilitation of housing damaged by the earthquake in Aleppo, Latakia and Hama provinces. The loan has a financing amount of up to SYP 18 million (approximately $2,450 according to the current black market exchange rate of SYP 7,350 to the dollar) over a six-year repayment period, without interest.

Even so, Abu Firas does not expect to obtain alternative housing anytime soon. He rules out rebuilding with a loan, “no matter if it’s interest free,” because he, like many other Syrians, lives life “day by day.” He cannot afford to repay installments. Instead, he is currently looking for a house to rent in one of Latakia’s suburbs.

This report was originally published in Arabic.