‘Locusts’: Organized looting, destruction of displaced Syrians’ homes by ‘demolition forces’ and regime-affiliated groups

The homes of Syrians displaced from regime-controlled areas including Yarmouk camp and the southern Idlib countryside are being systematically looted and destroyed in their absence, as Damascus-affiliated groups tear them apart in search of materials that can be recycled and sold.

26 May 2023

PARIS — In the days after the Syrian regime took control of the southern Idlib countryside village of Kafruma in January 2020, the victors began a new task: looting. Entering the vacant homes of those who fled, regime forces and affiliated militias stole what they found inside, including electrical appliances and furniture. One of those homes belonged to Said al-Hamid, an engineer from the village.

By the time regime forces entered, al-Hamid and his family had already fled, leaving their home and furnishings behind them. Their belongings, like those of many others displaced by conflict in Syria, would fall prey to taafish—a local term used to describe pillaging and theft by regime-affiliated groups.

After plundering houses in Kafruma, regime-affiliated groups proceeded to “demolish the roofs and parts of the walls to pull out the iron, water and electrical fixtures,” al-Hamid told Syria Direct. His own home was “looted, but its roof was not demolished, unlike most other houses in the village, because the regime forces used it as a military headquarters,” he said.

Since fleeing his house more than three years ago, al-Hamid has not been able to physically access it due to security concerns. But he still monitors its condition periodically using satellite imagery, and stays updated through information provided by residents in the area.

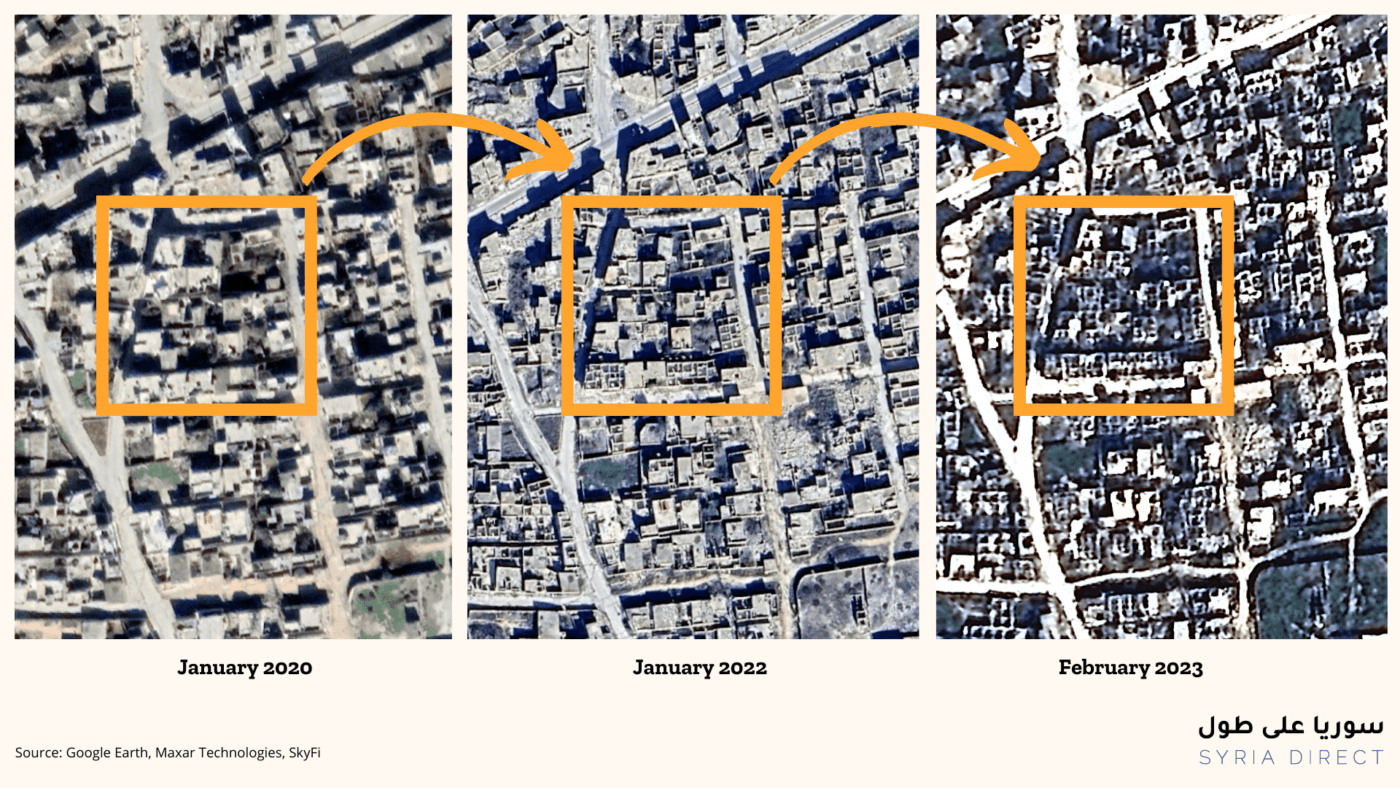

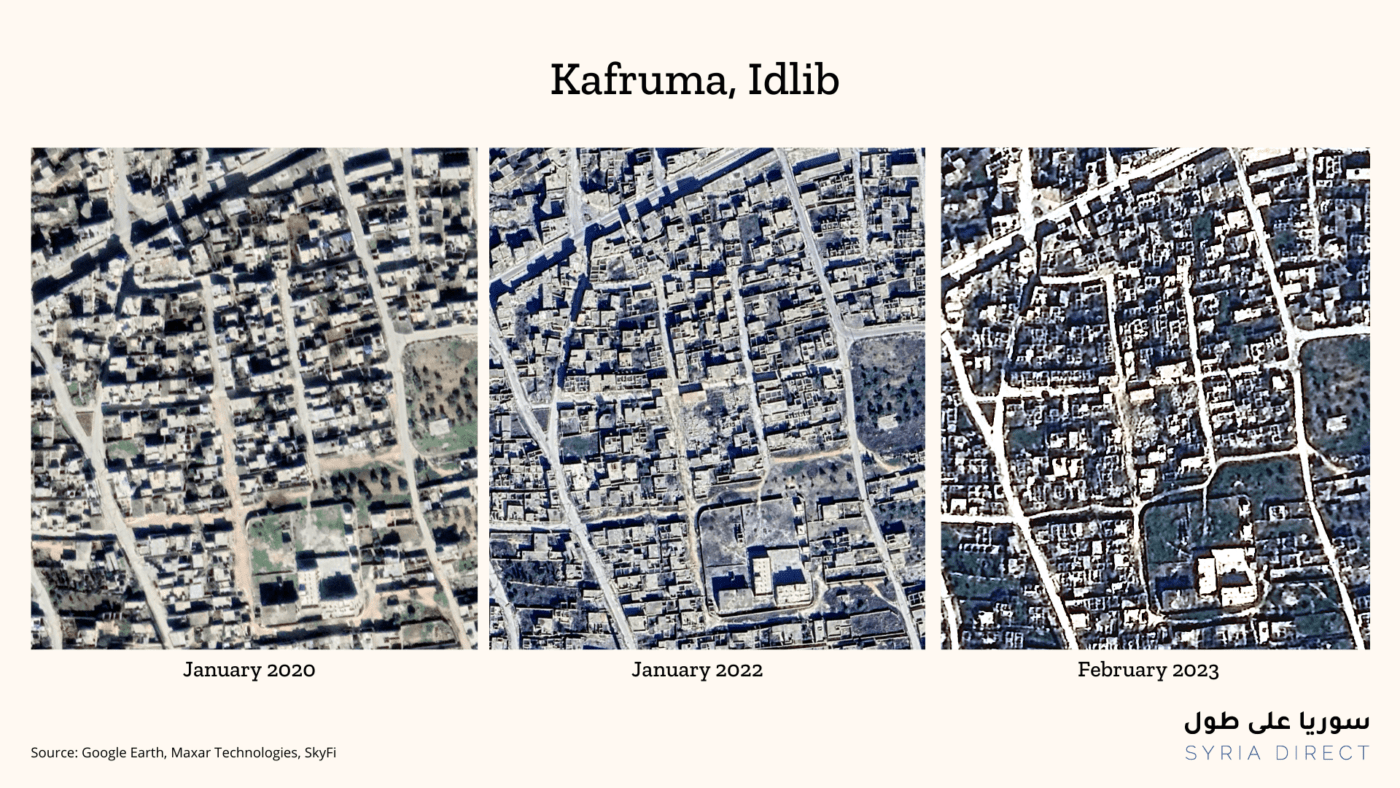

Satellite images show changes to the Idlib countryside village of Kafruma, starting in January 2020 (left), the month when regime forces took control of the town. In January 2022 (center), two years later, dozens of homes’ roofs have been destroyed. And in February 2023 (right), continued roof demolitions and damages to civilian homes are apparent (Google Earth/SkyFi/Syria Direct)

Hundreds of kilometers to the south in Damascus, journalist Amal al-Dimashqi—unlike al-Hamid—is able to visit the home she and her family fled. It lies in Yarmouk camp, in the south of the capital city. She goes every few months, allowed to visit for a few hours with the permission of regime security forces. But while she can visit, she cannot do anything to address ongoing violations against her family’s property, she told Syria Direct, asking to be identified by a pseudonym for security reasons.

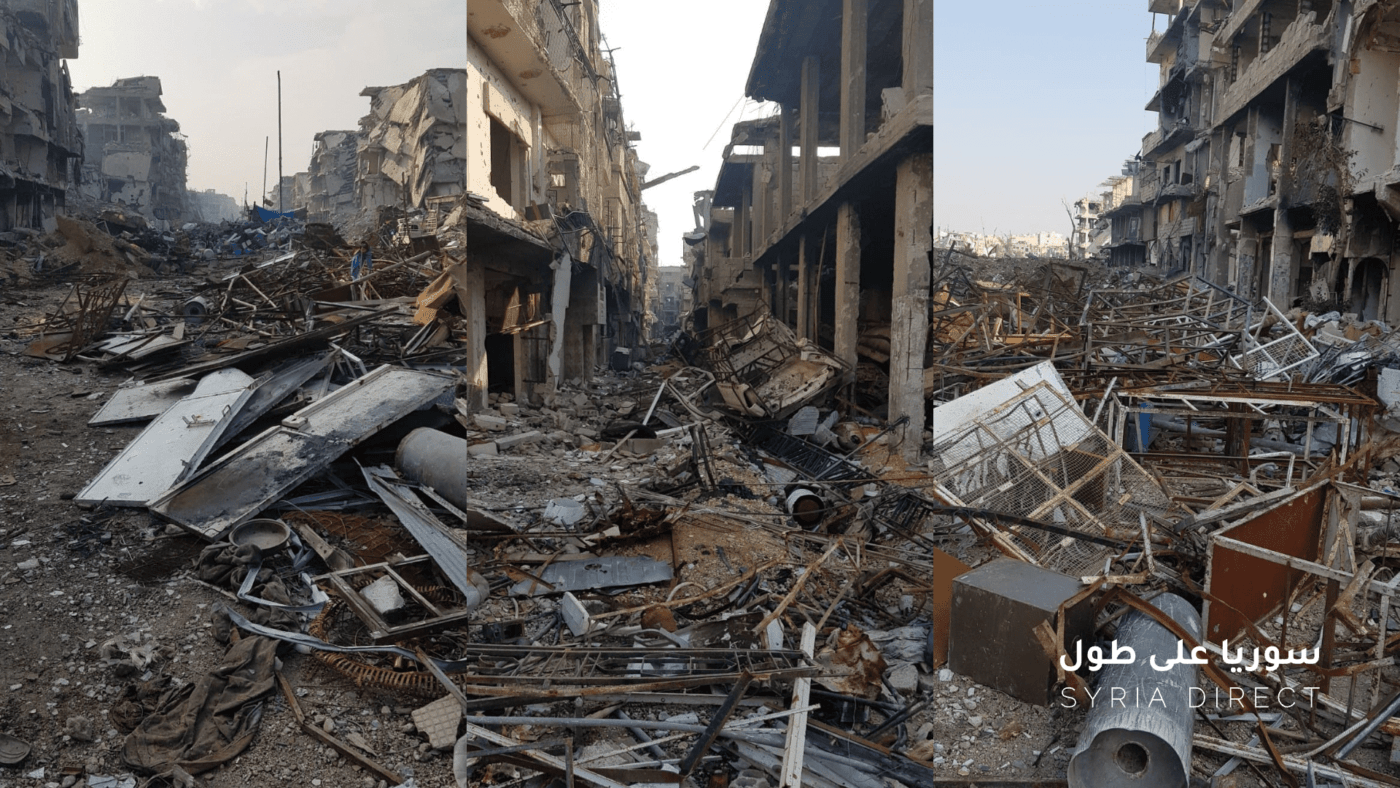

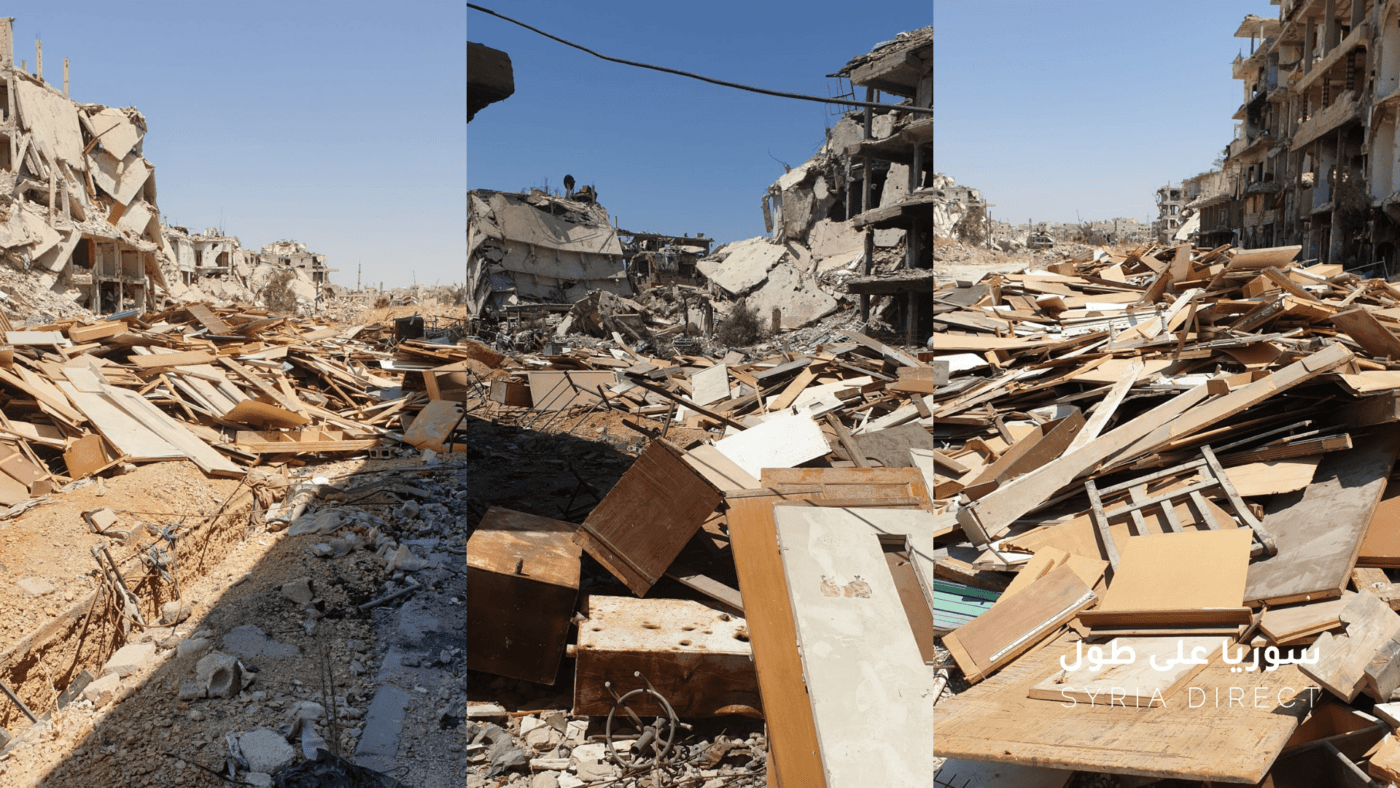

During her most recent visit several weeks ago, al-Dimashqi discovered that “the building was more damaged than in my previous visit earlier this year.” What remained of “the staircases, along with some ceilings and walls, had been demolished to extract valuable resources such as iron, water pipes and electrical wires to sell,” she said.

Al-Dimashqi provided Syria Direct with several pictures she took during her latest visit and consented to their publication. Her testimony also aligns with an online survey conducted by the Action Group for Palestinians of Syria in May 2021 with displaced residents of Yarmouk camp. In it, 93.2 percent of the respondents reported their homes underwent looting “involving furniture, doors, windows, electrical wires, etcetera,” while 6.7 percent said their houses “remained untouched.”

Iron collected from destroyed buildings in Yarmouk camp in south Damascus is piled up before being transported out of the camp to be sold, 2/1/2023 (Amal al-Dimashqi/Syria Direct)

Al-Dimashqi and al-Hamid’s stories are snapshots of the plight of displaced Syrians whose homes in regime-controlled areas are being systematically looted and destroyed. In their absence, their properties are being picked clean, to the point of “recycling the cement rubble,” al-Dimashqi said. “The looting of civilian homes has become a source of funding for warlords, regime officers and militias.”

‘My life’s work is gone’

When his native Kafruma was under opposition control, Abu Jaber worked as a “monitor,” tracking air traffic and alerting civilians to possible regime airstrikes. After he—like al-Hamid—fled with his family in 2020, he put his experience with mapping and satellite imagery to work, keeping a vigilant eye on his four-room house from a displacement camp near the Turkish border.

In 2021, a year after he was displaced, Abu Jaber discovered that his house in Kafruma had been demolished, and all the trees in his orchard cut down. “My life’s work is gone,” he said, in a voice filled with sadness.

Kafruma, Abu Jaber and al-Hamid’s hometown, is not an isolated case. Other villages and towns in areas recaptured by Damascus in northwestern Syria—such as the cities of Khan Sheikhoun, Maarat al-Numan, Morek and Kafr Nubl, and the villages of Hass, Jarjanaz, Deir Sharqi, al-Tamana, al-Habit, Masrin, Bazarin and Maarat Horma—have also seen demolitions and looting operations, sources displaced from these areas told Syria Direct.

The sources stated that demolitions are on the rise in villages and small towns, particularly those located near frontlines with opposition forces. These areas are virtually depopulated, as the regime has not allowed their residents to return, and local buildings have slab roofs reinforced with large amounts of iron, making them prime targets for demolition and looting.

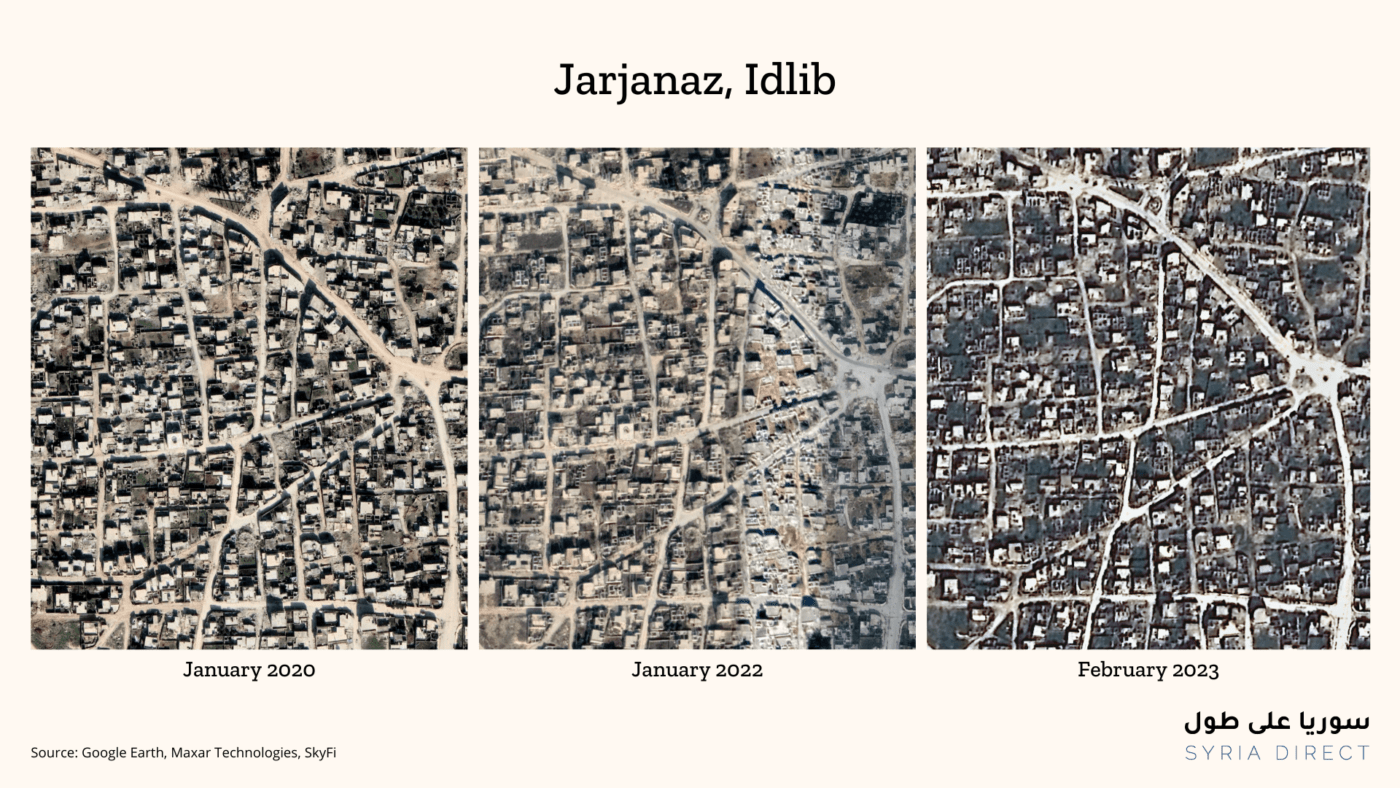

Satellite images of Jarjanaz, a town in southern Idlib, show it as it was in January 2020 (left), one month after the regime took control. In January 2022 (center), dozens of houses have lost their roofs. And in February 2023 (right), further evidence of roof demolitions appears (Google Earth/SkyFi/Syria Direct)

“Looting operations start with taking out household furniture and end with demolition,” said Bilal Satouf, a research assistant at the Omran Center for Strategic Studies who specializes in looting and demolitions in the southern Idlib countryside. Attacks on real estate in the area have “gone through multiple stages,” he explained.

In 2020, regime forces led by Suhail al-Hassan’s 25th Special Mission Forces Division—commonly known as the Tiger Forces—stormed and seized the southern and eastern Idlib countryside. Captured villages and neighborhoods were then distributed between different officers, Satouf explained.

These officers “granted looting contracts to merchants linked to them or their military brigades and militias, frequently through familial ties with battalion commanders or pre-established business connections,” Satouf said. For example, the Tiger Forces-affiliated al-Taramih forces—which consist mostly of fighters from the Hama countryside village of Qamhana—brought in a merchant from their hometown with connections to the militia’s commander to manage the looting operation, he said.

In the first stage of organized looting, contracts are granted to merchants “for looting all electrical appliances within the controlled area with a prearranged sum agreed upon with the officer,” Satouf explained. In the second stage, “a similar process is applied to wood, household furniture and bedrooms, which may involve either a different merchant or the same one.” The third stage entails “contracts for looting electrical wires, ceramics and tiles.” The fourth and last stage involves “granting contracts for extracting iron from roofs, pillars, stairs and other components,” according to Satouf.

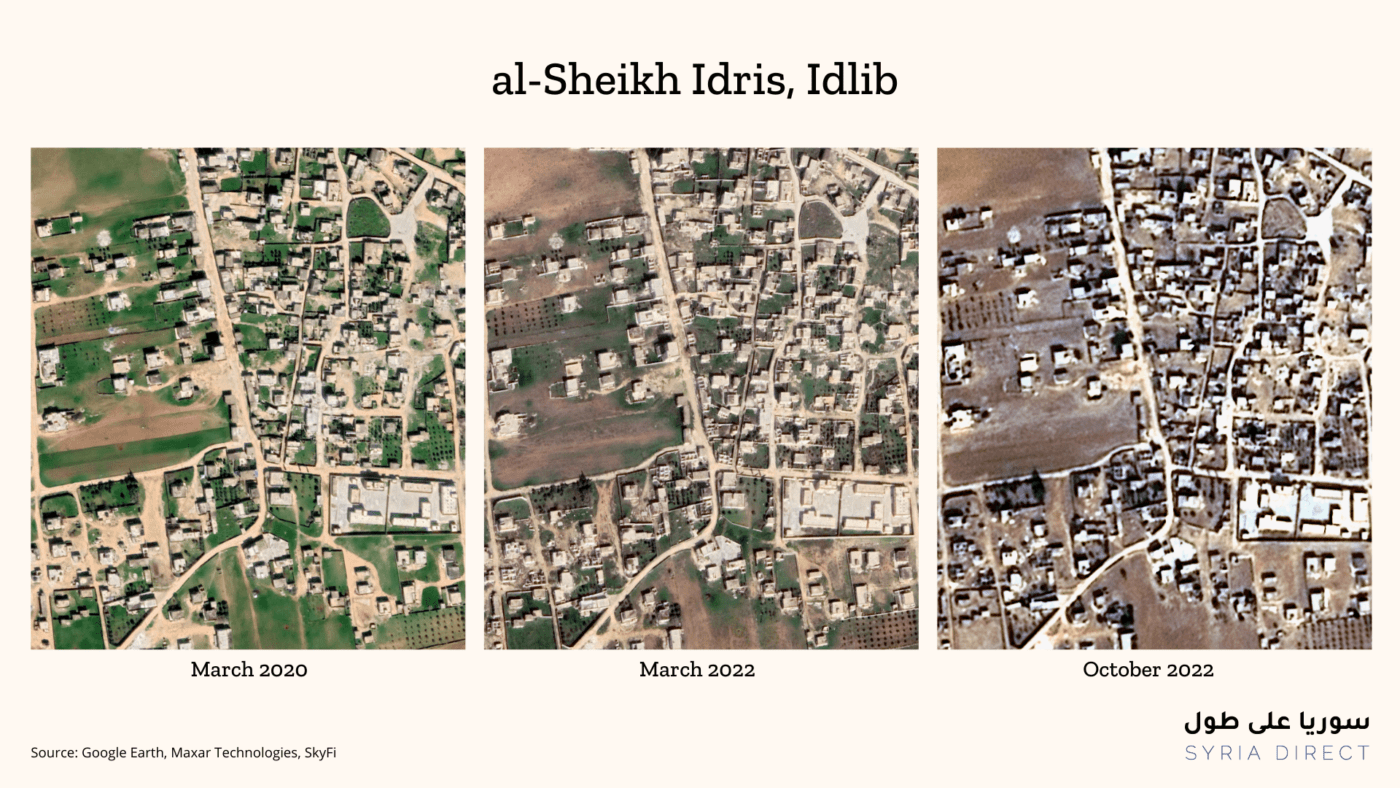

Satellite images of al-Sheikh Idris, a town in southern Idlib, shows it as it was in March 2020 (left), seven months after the regime took control. In March 2022 (center), dozens of houses have lost their roofs. And in October 2022 (right), further damage to homes appear (Google Earth/SkyFi/Syria Direct)

Seized crops and intact houses

Violations of housing, land, and property rights have proliferated in areas Damascus retook control of through settlements with opposition forces across the country in 2018, as well as those captured through military operations in southern Idlib in 2019 and 2020. In addition to looting and demolitions, land belonging to displaced residents has been offered in public auctions and harvests have been subject to extortion.

Around a year ago, Muhammad al-Ahmad’s brother traveled from Damascus to visit their family’s house in Tel Mardikh, a village in Idlib’s eastern countryside. He bribed a regime officer to access the village, “which is still a military zone whose residents are prevented from returning by the regime,” al-Ahmad, who currently resides in Idlib, told Syria Direct.

His brother told him “the village was extensively looted,” al-Ahmad said. “Electrical wires, ceramics and tiles were removed, but the houses were not completely demolished like in the neighboring villages.” He believes this is because “the regime repurposed the village as military barracks, training camps for militias and a venue for holding graduation ceremonies for fighters.”

While many houses in Tel Mardikh were left intact, “all the olive trees on [my land] were destroyed,” al-Ahmad said. Lands belonging to some friends of his in a village a few kilometers to the south also had “all their trees cut,” but also had “their roofs demolished and their contents looted, including floors, electrical wires and water pipes,” he added.

Another village, al-Tamanah, in southern Idlib, “has experienced relatively less destruction compared to other areas as the regime has allowed civilians to return,” Satouf explained. However, violations of property ownership rights have manifested differently. “The economic advantages of Aleppo’s pistachio production outweigh the benefits of demolishing houses for the regime forces, so they have imposed royalties on agricultural lands in towns renowned for their thriving pistachio crops,” he said.

Volunteer demolition forces

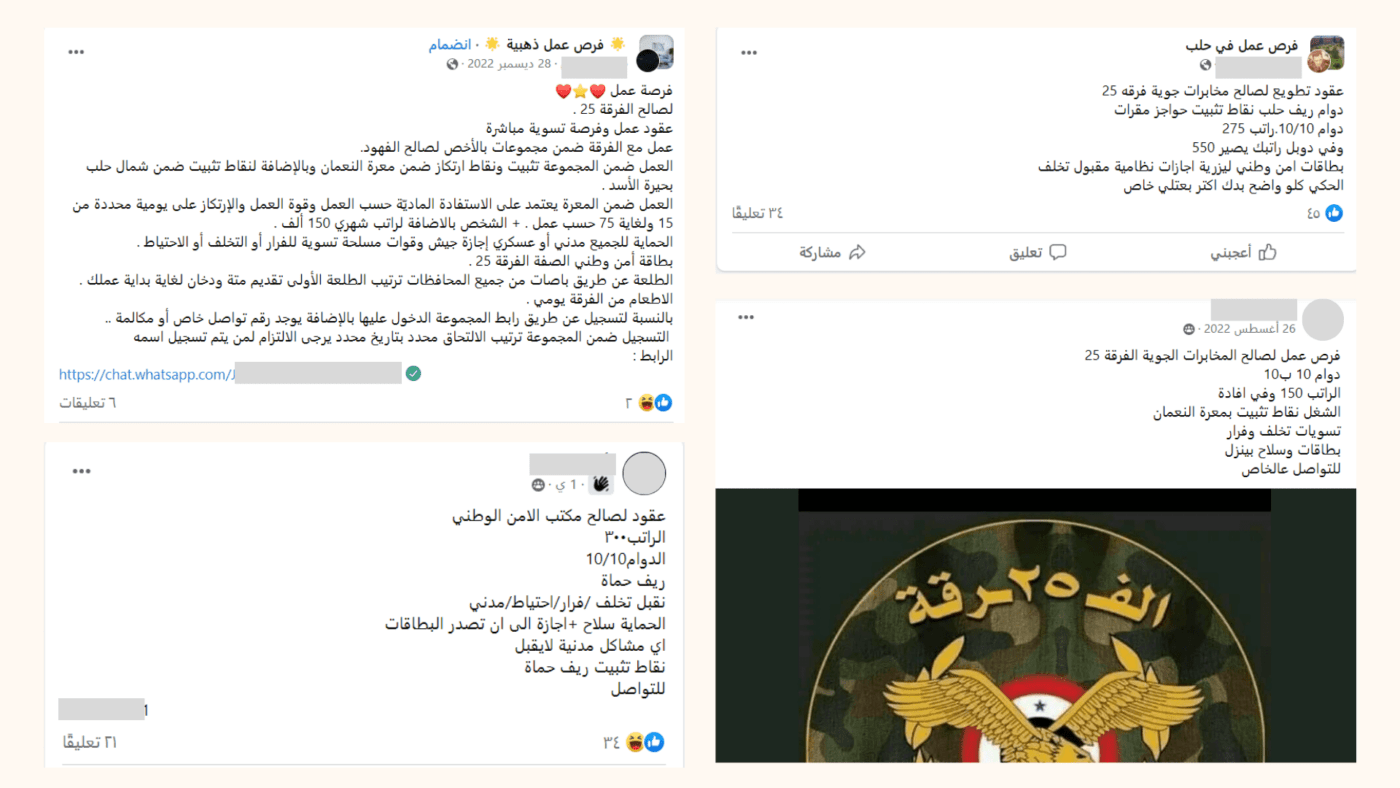

Syria Direct identified a significant number of social media posts over the past several months advertising “affiliation contracts” with regime security and military services in several parts of the country, including where house demolitions are taking place in the southern and eastern Idlib countryside.

The authors of these posts emphasized that affiliates could receive additional pay on top of their monthly salary by working in house demolition operations.

Screenshots of Facebook posts from the past several months advertising “affiliation contracts” with Syrian security and military forces in several parts of Syria (Facebook)

To verify these posts, a Syria Direct reporter contacted two numbers listed, posing as a young man interested in an affiliation contract with a military group in the Idlib countryside. The individuals he called each instructed him to contact “the boss” for further information on the contract’s nature, the place of work, monthly salary and other pertinent details.

The reporter contacted one “boss” he was referred to, who identified himself only as Ali, an Air Force Intelligence officer, and who confirmed the existence of “work contracts in the Aleppo and the Idlib countryside for Air Force Intelligence or the Iranians with a monthly salary of SYP 250,000,” or $28 according to the current parallel market exchange rate of SYP 8,850 to the dollar.

Ali added that there was an “opportunity to earn an additional income of SYP 15,000-25,000 ($1.60 to $2.80) a day by engaging in activities such as collecting iron or firewood.” The officer offered Syria Direct’s reporter several incentives related to working hours, vacation days, checkpoint privileges and the option to carry weapons during leave.

In a separate conversation, a man who identified himself as Thaher, an officer from the Tiger Forces, also confirmed “there are affiliation contracts in Aleppo and the Maarat al-Numan area with the Tiger Forces, for a monthly salary of SYP 250,000 [$28].” He, too, noted the opportunity for additional work “in house demolitions in Maarat al-Numan for SYP 10,000 [$1.10] per day.” However, he added, “the additional income is even higher in Aleppo, potentially reaching SYP 25,000 [$2.80], particularly by logging or collecting iron.”

Thaher added that “if you bring a group of guys with you, it could result in a higher salary and additional compensation for each person.”

Wood collected from destroyed buildings in Yarmouk camp in south Damascus is piled up prior to removal from the camp, 2/1/2023 (Amal al-Dimashqi/Syria Direct)

Looting havoc at Yarmouk camp

Five years after Damascus retook control of the Yarmouk camp, known as the “Capital of the Diaspora” for its Palestinian population, most of its residents are still barred from returning to their homes without security approval.

A few years ago, during one such approved visit, Khalil Ahmad came face to face with people looting his home. “It’s one of the hardest things in life, walking into your house being looted and feeling powerless,” he told Syria Direct. Organized looters “operate with impunity, enjoy full protection from the security forces and the army, and have well-established hubs across the camp to gather what they have stolen,” he said.

Today, Ahmad is back in his house in Yarmouk’s al-Zein neighborhood, one of the few areas civilians have been allowed to return to—provided their homes are habitable. He called the groups targeting vacant properties in the camp “locusts” who “view everything as profit, so they work with an almost superhuman energy, leaving nothing behind in the areas they enter.”

While property owners in the Yarmouk camp mourn the loss of their belongings, Ahmad said looters “are willing to demolish a wall that would cost approximately one million Syrian pounds ($111) to rebuild, just to extract a water pipe worth only a few hundred pounds.”

Among the looting groups operating in the Yarmouk camp are young men, women and children from the Dom community, who collect iron and rubble remnants from homes for a daily wage, under the protection and employment of security and military services, two sources told Syria Direct.

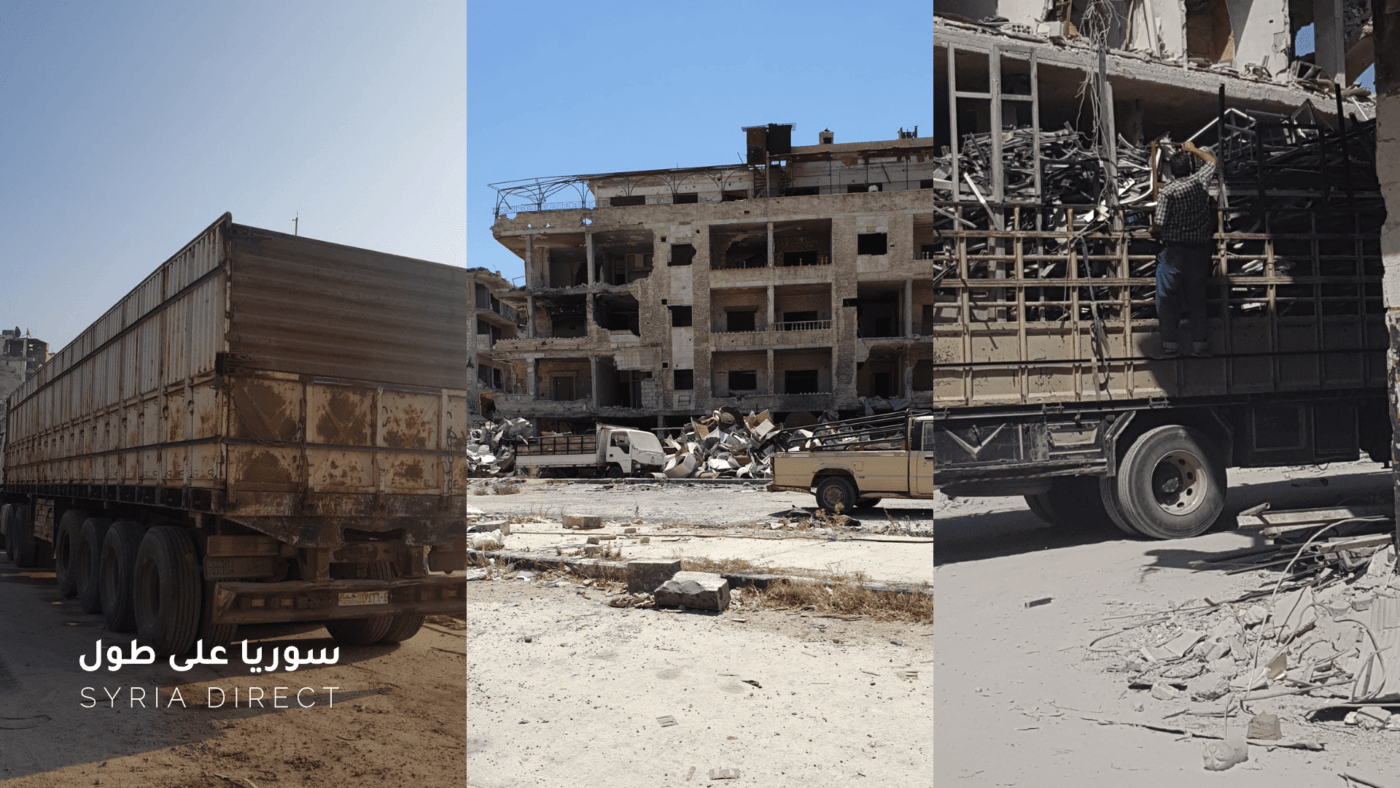

Ahmad said no demolition or looting operation could take place in the camp without the knowledge or supervision of the security services, noting that “the recovered materials are gathered, sorted, and transported by large trucks through various checkpoints and security posts.”

On the left, a truck enters Yarmouk camp in south Damascus to begin transporting materials collected from destroyed buildings out of the camp. In the middle, the tan truck in the foreground has been used to transport a group of looters inside the camp, while the white truck in the background is being used to collect looted materials. On the right, iron is loaded onto a truck in the camp, 2/1/2023 (Amal al-Dimashqi/Syria Direct)

The involvement of security and military services in the camp extends beyond protecting the groups responsible for violating displaced residents’ properties or facilitating their movements. “Military recruits actively participate in looting, earning daily wages just like the Dom,” journalist and Yarmouk native al-Dimashqi said.

During one of her past visits to her home in the camp, al-Dimashqi said she came across military personnel digging in front of her house in an attempt to extract water pipes from the main water network. “The attacks go beyond private property and extend to public property and infrastructure,” she said.

After the Syrian regime retook control of Yarmouk camp in May 2018, al-Dimashqi entered to inspect her family’s building. She noticed that “all the furniture was still there in the apartments, except for the electrical appliances, which had been stolen during the initial days after the regime came in,” she recalled. However, when she visited the camp again two months later, “everything had disappeared from the apartments.”

Law does not protect rubble

Organized demolitions and looting is a trend that emerged over the past 12 years in the wake of the Syrian revolution and ensuing conflict. Accordingly, “Syrian law and the constitution have not been updated to criminalize this phenomenon,” one Syrian lawyer told Syria Direct, requesting anonymity for security reasons. Existing “Syrian laws deem theft and looting to be [regular] criminal offenses,” not organized war crimes.

Rather than acting legislatively to safeguard the property of displaced people, the state “has enacted laws such as the Terrorism Law which permits the confiscation of property belonging to those accused of terrorism, as well as the Flag Service Law and Law No. 10 of 2018 and its predecessor, Decree 66,” the lawyer said. Each of these pieces of legislation particularly threaten the property of displaced people, especially those seen as opposed to Damascus.

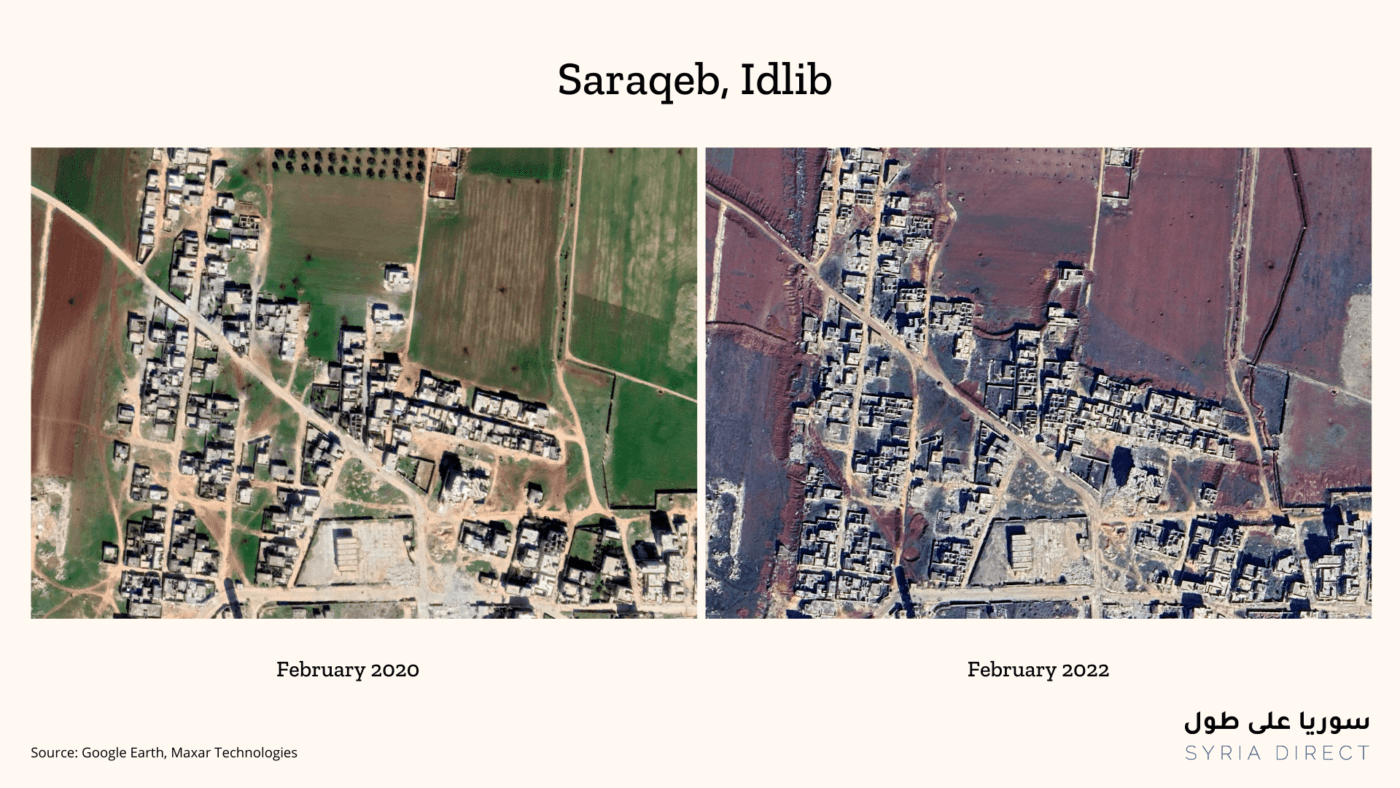

Satellite images show Saraqeb in February 2020 (left), one month before regime forces took control of the city. Two years later (right), the roofs of dozens of houses are gone (Google Earth/Syria Direct)

International law and norms hold that the property of displaced people must be protected, and pillage is a war crime in both international and non-international armed conflicts—as in the case of Syria—under customary international law.

The United Nations’ guiding Principles on Housing and Property Restitution for Refugees and Displaced Persons, also known as the Pinheiro Principles, emphasize the importance of protecting the assets and property of internally displaced people, particularly from looting, indiscriminate attacks and acts of violence.

They also prohibit the use of property as shields for military purposes, retaliation or collective punishment, and call for abandoned assets and property to be safeguarded from arbitrary destruction, appropriation, occupation and use.

Article 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) states that “the destruction and appropriation of property without military necessity is a war crime, especially when it is committed within the framework of a plan or general policy or within the framework of widespread commission.”

Syria is not a party to the Rome Statute, however, which means the ICC has no jurisdiction over Syria unless it is referred to the court by the United Nations Security Council. Past efforts to refer Syria to the ICC have been repeatedly blocked by Russian and Chinese vetoes.

Whether prohibited by law or not, it is clear that the systematic looting of displaced Syrians’ property by regime-affiliated groups, or with their knowledge and consent, continues apace across the country.

In Damascus, al-Dimashqi fears for the future of her family’s property in Yarmouk. “I worry that the building could be completely destroyed within a month,” she said. “Even the rubble of your home no longer belongs to you.”

This investigation was originally published in Arabic. It was translated into English by Nouhaila Aguergour and edited by Mateo Nelson.