Manufactured winter misery in Arsal

Due to Lebanon’s collapsing economy and restrictions on building permanent structures, Syrian refugees are facing an especially difficult winter in wood and plastic tents.

7 February 2022

ARSAL — As a blanket of snow covers the surrounding mountainside and fruit trees, Muhammad Abu Bakr and Khazna Fayyad’s three children wander around their tent in northern Lebanon. They are wearing sandals without socks, their feet covered in mud and snow.

The family has spent eight winters in this tent. Originally from the Homs city of al-Qusayr, they are among 85,000 Syrian refugees who live in 208 informal settlements in and around Arsal, a town in Lebanon’s northern governorate of Baalbek-Hermel, which hosts some 340,000 Syrian refugees.

A Lebanese government ban on the use of what it deems “permanent” building materials in tent settlements leaves refugees facing snowstorms in tents made of wood and plastic. And while the policy has been in place for years, this winter is especially harsh due to an unprecedented economic crisis in Lebanon that has pushed 90 percent of Syrian refugee households below the extreme poverty line.

It is dark and humid inside Muhammad and Khazna’s tent, a structure of wood, plastic and insulating material with a wall four cinder blocks high separating the kitchen and main room. In the latest storm, water poured into the room where the family spends most of their time gathered around the stove (sobia) sitting on thin mattresses. A thin layer of frozen water still covers the kitchen floor. The family pays the landowner $100 rent per year to live in the tent.

“At night, temperatures drop below freezing. Even with all the blankets on top of us, you still feel cold,” Khazna told Syria Direct. “If you don’t stay close to the stove at night, it is very hard,” added Muhammad. In Lebanon, 57 percent of Syrian refugees live in substandard shelters.

Muhammad Abu Bakr stands next to his family’s tent in Arsal, 02/02/2022 (A. Medina, Syria Direct)

The family receives 300,000 Lebanese lira (LBP), or around $15 at the parallel exchange rate, per person each month from the UNHCR, with an additional 1,800,000 LBP ($90) as winter assistance. “It is not enough,” Muhammad told Syria Direct, explaining that the cost of fuel for the stove for one month comes to 2,600,000 LBP ($130). The family is 2,000,000 LBP ($100) in debt.

“We can’t afford lentils, rice or meat – we only eat bread, zaatar and olive oil. Go and see the kitchen, do you see anything to eat?” asked Muhammad, gesturing at a kitchen that is empty except for a bit of bread and spices. “Look at my three-year-old son’s lips, they lack color because he doesn’t have enough vitamins.”

Like Muhammad’s family, an estimated 50 percent of Syrian refugees are food insecure. Lebanon has recorded the third-highest inflation—145 percent—in the world, after Venezuela and Sudan. Food prices have gone up 404 percent since 2019.

“This isn’t living; there’s no humanity in our situation,” said Muhammad. “I feel like I’m suffocating. Psychologically, there’s a lot of pressure on us.”

Pressure on the family increased in late January, when Lebanese soldiers who inspected their tent ordered them to demolish the low cinder block wall between the tent’s kitchen and main room, which Muhammad plans to do in the coming days. He says he was told that cement walls separating rooms, regardless of size, are forbidden.

Back in 2019, Lebanon’s Higher Defense Council ordered the demolition of “permanent structures” that Syrian refugees had built in Arsal, arguing they violated housing codes. The interpretation of what constitutes “permanent structures” seems fluid. At the time, the army ordered Syrian refugees to demolish any wall taller than five cinder blocks. Five thousand Syrian families in Arsal did so.

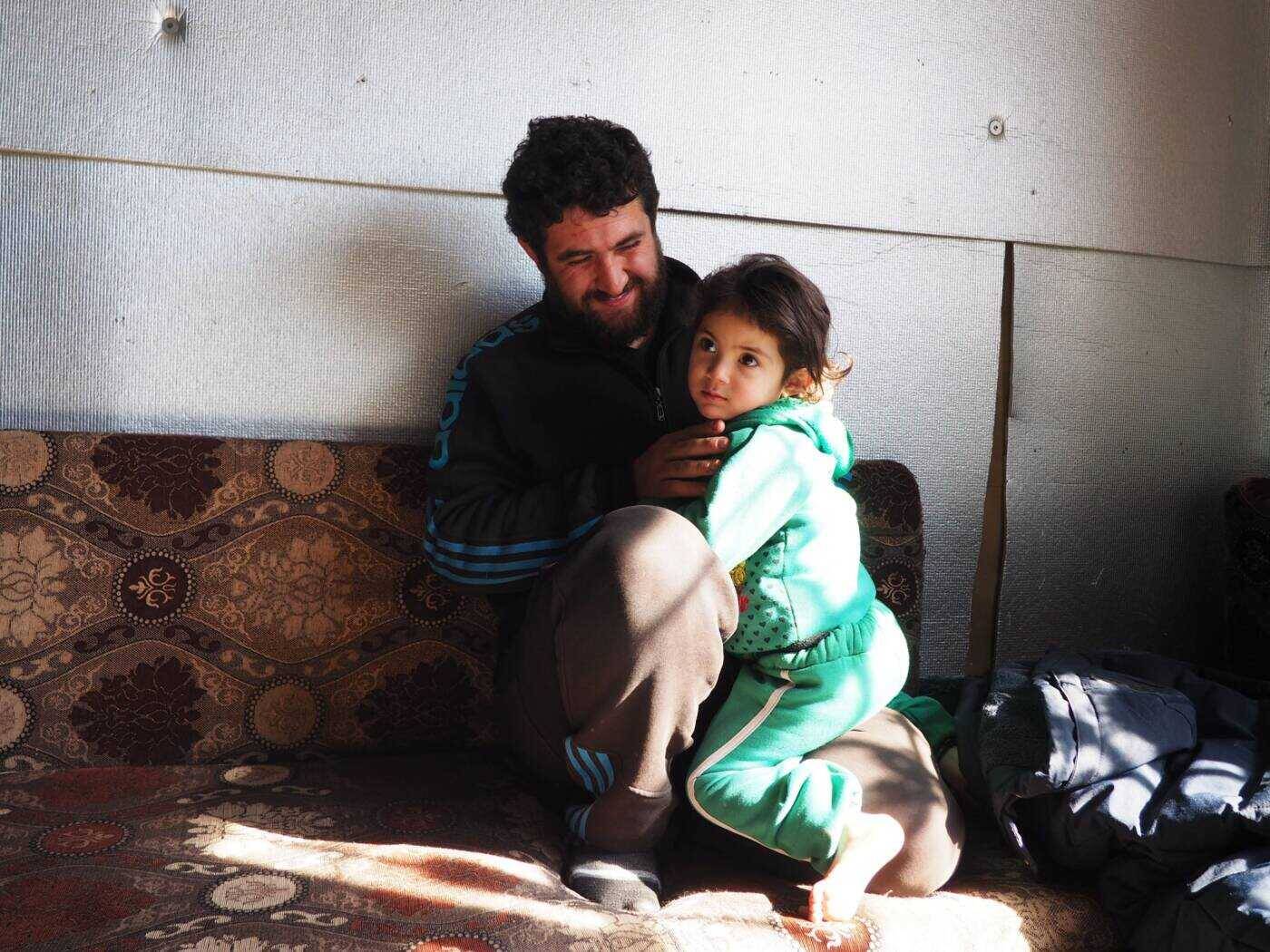

Ahmad Sadiq with his daughter in their tent in Arsal, 02/02/2022 (A. Medina, Syria Direct)

Ahmad Sadiq was one of them. Two years ago, the 29-year-old refugee from al-Qusayr tore down the upper part of the cement walls of his family’s tent in front of a Lebanese soldier. Then, two months ago, he received another visit. “The army came into the camp to check irregularities,” Ahmad said. This time, “they told me the cement walls between the rooms were forbidden.”

Ahmad has lived in a tent in Arsal with his wife and three children since 2017. When they first arrived in Lebanon in 2015 they rented a flat, but could not afford the rent. They then moved to this plot of land, where the landowner allows the family to stay for free because he “is a good person,” as Ahmad puts it.

Ahmad’s family also receives monthly payments and a sum for winter assistance from the UNHCR, but the money does not go as far as it used to. “At first, with the UNHCR food assistance, you could survive. Now it is very difficult,” said Ahmad, who is unemployed. “Twenty liters of fuel for the stove lasts three days and costs 360,000 LBP [$18],” he added. Since the Lebanese government lifted fuel subsidies last summer, prices have skyrocketed.

This winter, “1.2 million refugees (260,833 families) have received winter cash assistance,” UNHCR Lebanon’s spokesperson Paula Barrachina told Syria Direct. They received 930,000 LBP per month, covering up to five months. The budget for the UNHCR’s winterization plan 2021-2022 is $52.3 million. Partner organizations have also distributed winter items such as thermal blankets and sleeping bags, as well as shelter support items. “Still, the needs surpass the assistance provided, which is not enough for families to make ends meet,” said Barrachina.

The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is tasked with responding to emergencies in Arsal. In January, following a severe snowstorm, NRC distributed 74 kits to repair damaged tents and installed 14 new tents—two of which were to replace collapsed tents—and 12 tents for families moving from a house to a tent.

Safa Abu Zaid and Muhammad al-Rifai were among those families. Since fleeing to Lebanon from the Qalamoun region northeast of Damascus in 2014, the couple had been living in houses in Arsal. Then, a few months ago, their landlord increased their rent to $100. Unable to pay, they moved to a tent provided by the NRC.

They are still adjusting to the damp floor and condensed water in the ceiling of their tent. “When the latest storm came, the whole tent shook from the wind,” Safa said. “I was wearing my street clothes to be ready just in case the tent went.”

“Even for Lebanese people, life is difficult, so how is it going to be for Syrian refugees? We haven’t eaten meat in four months,” said Muhammad al-Rifai, who is not able to work due to an injury in his hand.

Since moving into a tent, the couple struggles to keep warm. “We can’t afford fuel for the stove,” he said. “We paid 100,000 LBP [$5] for a small bucket of wood, and light it with cardboard, shoes, car tires—whatever I find.”

Dark in Lebanon, darker in Syria

Muhammad al-Rifai tries to heat his tent using a shoe as fuel for the stove, 02/02/2022 (A. Medina, Syria Direct)

Al-Rifai feels trapped. “I can’t return to Syria, I can’t go to a third country, and in my 10 years in Lebanon I can’t even afford a window,” he said.

Ahmad also cannot envision returning to Syria. “I am not going to carry weapons and kill someone or get killed, no matter how dark the situation is in Lebanon,” he said. “I will not return to Syria…if there was security in Syria, I would return tomorrow,” he added.

A recent report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) documented the dangers facing Syrian returnees. “Our report demonstrated the fears and realities that people face when they go back to Syria,” HRW researcher Nadia Hardman told Syria Direct. “As long as Assad is still in place, people do not intend to go back, so we have a responsibility to ensure that Syrian refugees in Lebanon have a dignified life in the meantime.”

If limitations on building materials or construction were lifted, this “would alleviate people’s ability to live a dignified life,” said Hardman, adding that “there’s a strong humanitarian community ready to do the kind of restructuring and winterization to really build dignified homes.”

“More than a decade into the Syria crisis, we see refugees living in these terrible conditions every single winter,” said Elena Dikomitis, Advocacy Manager at NRC Lebanon. “This is a collective failure of the international community and the Lebanese government.”

HRW researcher Hardman stressed that countries neighboring Syria, such as Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey, continue to bear “the brunt of the refugee crisis,” and called for an increase in resettlement outside the region.

“Lebanon is crumbling, and cannot fulfill [a] dignified life for refugees.”