New legal initiative launches for ‘invisible’ families of Syria’s countless detained and disappeared

The stories are often similar, repeated tens of thousands of times over: uniforms bursting through the door, loved ones taken away. Then, the silence.

28 March 2019

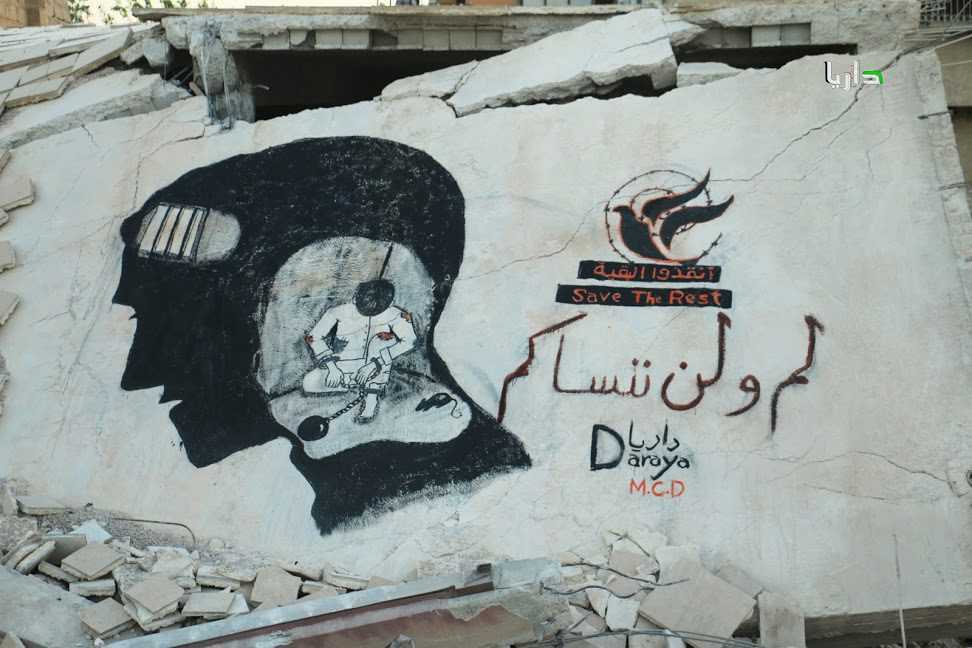

A mural on rubble in Daraya memorializes people forcibly disappeared in 2016. Photo courtesy of Majd el-Maaddamani.

The stories are often similar, repeated tens of thousands of times over: uniforms bursting through the door, loved ones taken away. Then, the silence.

More than 95,000 Syrians have been forcibly abducted in Syria since the outset of the 2011 Syrian uprising and ensuing conflict, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights monitoring group, with some 80,000 arbitrarily arrested or forcibly disappeared by the Syrian government and its sprawling security apparatus.

Families of the missing still live with the aftermath.

“These families are somehow invisible to the international community,” says Syrian international human rights lawyer Noura Ghazi, who recently launched Nophotozone, a new legal support and advocacy initiative focused on the issue of detention in Syria.

“[The international community] talks about them, talks about their suffering, talks about a solution and yet nothing is happening.”

Nophotozone was originally an idea shared by Ghazi and her late husband, Palestinian-Syrian human rights defender and web developer Bassel Khartabil.

Arrested by military intelligence on March 15, 2012, he would spend years being transferred from one facility to the next—sometimes being held in solitary confinement. Khartabil was also detained in Sadnaya, the notorious prison complex recently described by Amnesty International as a “human slaughterhouse.”

Ghazi went years hoping for his release, only to find out—in 2017—that her husband had been executed incommunicado two years before, without the family’s knowledge. On August 1, 2017, she took to Facebook to announce the news of Khartabil’s death.

“I was the bride of the revolution because of you. And because of you I became a widow,” she wrote. “This is a loss for Syria. This is loss for Palestine. This is my loss.”

While talk increasingly turns to the pressing issues of refugee returns and Syria’s post-war reconstruction pending an elusive political solution to the conflict, the families of the detained live with daily memories, trauma and—for those who never got definitive word about what’s happened to their loved ones—a kind of hope that never goes away. Until now, the Syrian government has only issued death certificates for some 10 percent of the estimated 80,000 people missing.

At the international “Brussels III” conference, hosted by the European Union and United Nations earlier this month, Syrian civil society representatives complained about what they saw as the international community’s disinterest in keeping issues of transitional justice at the heart of the conversation around Syria.

One participant at the conference, Amneh al-Khoulani from the Families for Freedom group that also represents the families of detainees in Syria, expressed dismay that they “struggled so that the detainees issue…would [even] be on the agenda at this conference.”

It’s a concern shared by Ghazi. In this interview with Syria Direct’s Tom Rollins, she discusses her hope that initiatives like Nophotozone can put the focus back on tens of thousands of people vanished into detention and provide their families with the “interest” and “encouragement” that she feels she received following the announcement of Khartabil’s death.

“I want other people who really suffered to have the same interest. [We’re not talking] about 10 people in Syria, this is [affecting] hundreds of thousands of families in Syria.”

“They have to be seen, and to be a part of this process of justice and accountability.”

Q: Bassel and yourself had the idea of Nophotozone from long before the announcement of his death. What was the original aim?

This organization was a dream of Bassil and I.

[At Nophotozone], we provide legal advocacy and legal advice for detainees and the families of the disappeared in Syria and Lebanon. It’s a non-political organization, and works for all of the detainees and disappeared regardless of the party who arrested or disappeared them.

We are targeting women because most of the missing people are male. We are targeting Syrian women in refugee communities in Lebanon, [mostly] in the Beqaa, through weekly sessions. We advise them about what they have to do when there’s a person missing from the family, and the legal impact.

And also we are focusing on legal empowerment by raising awareness about some basic legal terms, some basic knowledge—human rights, refugee rights, women’s rights—and also in terms of arbitrary detention and forced disappearance. We’re also trying to build a kind of network among these women to work on capacity-building, so that they can represent themselves. We believe that these people are direct victims, so they have to be part of the solution.

It’s important to raise [this issue] among the Syrian community, and also the international community. What is arbitrary detention? What is forced disappearance? Why is this the most complicated issue among all the issues in this conflict?

I always say this, but I feel I was lucky that I got all the interest of the international community, the media and [international NGOs]. So I want other people who really suffered to have the same interest. [We’re not talking] about 10 people in Syria, this is [affecting] hundreds of thousands of families in Syria.

They have to be seen, and to be a part of this process of justice and accountability.

Q: You mentioned about ‘being seen.’ In your view, what did that sense of visibility gave you, during Bassil’s detention and following the announcement of his death?

It was a kind of coincidence that I had a father who was detained nine times, and had a husband who was detained and executed, and that I’m a human rights lawyer specialized on the topic of arbitrary detention and forced disappearance.

So I got this interest from the embassies, media, different organizations and it helped. I felt that, ‘Okay, there are people that are interested, that will take care of me.’ When I left Syria in 2018, I felt that I had options to go to Europe and this opportunity to speak loudly and to travel from place to place to talk about my own experience and also the issue [itself].

I’m not saying that I’m getting over this. I’m just learning how to live with it for my entire life. But what helps me is that…it’s a kind of encouragement. I realised that because of this interest, I have an impact. I have a role to play. So I need to be strong, to be stable.

I feel that other people deserve to have this kind of interest as well.

Q: You talked about the complex nature of the detainees issue—or the complex politics of it, perhaps—but also the international community’s response to it. What do you mean exactly?

I was in Brussels, and I talked there about what I called ‘short-term justice.’ These families are somehow invisible to the international community. [The international community] talks about them, talks about their suffering, talks about a solution and yet nothing is happening.

It’s not about cases in some European countries, it’s not just about accusing the Syrian regime as the one with the main responsibility for these crimes. These are all very important as steps towards justice in Syria, but we need a kind of international political resolution to stop these violations and to know the fate of all these people—whether they are alive or dead.

Until now, a lot of people are still detained and disappeared. [And] the majority of these people detained are actually disappeared—there is no information about their whereabouts or their fate or the reasons for their disappearance.

Q: There was a lot of talk at Brussels about reconstruction, refugee returns and the politics of aid programming inside government-held areas of Syria. The EU maintains that funds for things like reconstruction can go to Syria once there’s been a genuine political settlement in there—basically, meaning elections and so on.

Do you think it’s become harder to advocate around arbitrary detention and forced disappearance in this climate?

Actually, the Brussels conference was very important. This declaration from [EU foreign affairs chief Federica] Mogherini, that there would be no reconstruction or return without a political transition, was very important.

But I hope that they will look into reparations and rehabilitation for the families of the detainees and the disappeared. It isn’t just that [these families] are missing someone in the family. Most of them are women: they need to work, they have obstacles in their lives in neighboring countries—especially in Jordan and Lebanon. They are suffering. Most of them are [without legal residency]; they are not registered.

These families who don’t have death certificates for their husbands, they don’t get any humanitarian or medical aid.

We are talking about thousands of these families in neighboring countries. So they need a kind of immediate solution.

The international community shouldn’t do anything without solving [first] the [issue] of Syria’s detainees and disappeared—with real action and not just talking.

It has to be a priority file, [one that the international community solves] before they move on to the others.