Northeast Syria’s farmers brace for a catastrophic harvest amidst a severe water crisis

The wheat harvest is starting in northeast Syria amidst a regional drought. Local farmers expect very poor yields, which will have dire consequences as nearly 60% of Syrians are already food insecure.

26 May 2021

AMMAN — Pictures from May 2019 show Karim Kraf Abu Muhammad, a farmer from Raqqa province, standing in waist-high lush, green wheat, densely growing on his unirrigated field.

Two years later, the situation has changed drastically, as another picture shows. Although the wheat harvest should be starting, Abu Muhammad’s field is a far cry from the green sea of two years prior – instead, it is hard and parched soil, sparsely covered by shreds of dry grass.

“I expect this year’s harvest to be around a third of that of the previous year,” Abu Muhammad told Syria Direct, lamenting the lack of water that killed his crop.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) expects a below-average harvest this year due to drought conditions affecting Syria’s historical breadbasket. Likewise, the Syrian Minister of Agriculture has announced that the country faces the most severe drought in seventy years, indicating that more than half of the 1.5 million hectares initially planned for wheat cultivation have been lost.

Severe drought

The first rains came late into the season during November. Precipitation levels remained below average every month this winter, leading the Global Drought Observatory, a global drought-monitoring service, to issue a drought warning over Syria and Iraq in April. The lack of rain was compounded by warm temperatures in the spring that affected the plants in crucial development stages.

“Despite the high frequency of meteorological droughts in the past 25 years, the current drought stands out as one of the worst over the same period,” the Global Drought Observatory warned.

The eastern provinces, which provide around 80% of Syria’s yearly wheat and barley production, have been particularly affected, notably Hasakah province.

70% of the population in north and east Syria depend on the agricultural sector (farming and livestock combined) for a living.

The drought is due to severely impact food production in Syria, mainly because “an estimated 65 to 70% of agricultural surfaces planted with wheat and barley are rain-fed,” Salman Baroudo, co-chair of the economy and agriculture commission in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), the Kurdish-led governing authority in the region, told Syria Direct. These non-irrigated surfaces are locally known as the “ba’al” and generate the bulk of the yearly supply of flour and fodder.

Consequently, “the situation has generated a degree of fear and stress among the people,” Baroudo recognized, adding that around 70% of the population in north and east Syria depend on the agricultural sector (farming and livestock combined) for a living.

An irrigation crisis

For Abu Muhammad, who cultivates one hundred hectares of wheat and barley in the ba’al, the impact of the drought is catastrophic. His hopes for a good yield on his other fields, covering 30 hectares of irrigated land, have also been doused.

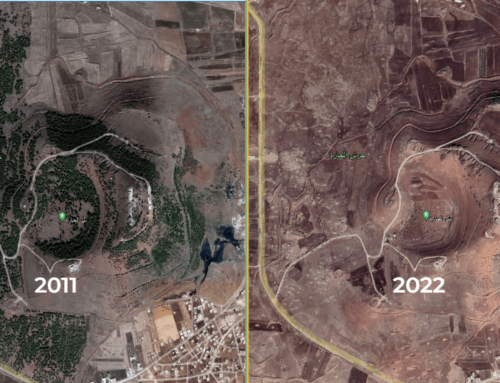

The water levels of dams in the region has dropped significantly this year due to the combined effect of a lack of rain and a decrease in the flow of the Euphrates River, which flows from Turkey and through Syria. The water line fell by more than four meters in Tishreen Reservoir and five meters below average in the Euphrates Reservoir (al-Assad Lake), in the western countryside of Raqqa.

Due to the electricity crisis, pumping stations serving irrigation projects have been running at around two-thirds of their regular frequency.

The AANES blames Turkey for decreasing the water flow in the Euphrates River upstream from 500 cubic meters per second, the supply provided for by agreements between Syria and Turkey, to 200 cubic meters per second.

Water has been a contentious topic between the AANES and Turkey since October 2019, when Turkey seized the main Alouk water station serving the city of Hasakah during an offensive against the Kurds in northeast Syria. The AANES has since regularly accused Turkey of weaponizing water by cutting off the supply to destabilize the region. It has similarly interpreted the decrease in the flow of the Euphrates, although Turkey itself is facing one of the worst droughts in its history, contributing to overuse of the river.

Further, the crisis has decreased the quantity of water available for irrigation while simultaneously limiting the supply of electricity generated from hydroelectric dams. Due to the electricity crisis, pumping stations serving irrigation projects have been running at around two-thirds of their regular frequency, according to an agricultural expert previously interviewed by Syria Direct.

Multiple hardships and mixed policies

“Farmers are no longer able to survive,” Abu Muhammad lamented. In addition to the water crisis, “we face difficulties due to the high cost of labor, the high prices of fertilizers and the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, which led to a shortage of labor,” Marwan Issa, a farmer from the countryside of Qamishli, told Syria Direct.

Agricultural inputs are imported into northeast Syria at a high cost to farmers, a situation which Baroudo blamed on the lack of international diplomatic recognition awarded to the AANES and its inability to enter trade agreements.

But farmers and agricultural experts contacted by Syria Direct also pointed out the lack of support from the AANES. “The autonomous administration did not take any actions to respond to the water crisis. A small percentage of farmers who have the capacity [adapted to] the drought using spray irrigation systems,” an agricultural project manager from a large INGO, requesting to stay anonymous, told Syria Direct.

The expert added that no measures have been reported to support the harvest this year, other than increasing the purchase price of wheat and barley compared to the previous year, considering the Syrian pound exchange rate against the dollar.

On May 19, the AANES announced the price at which it would purchase cereal from farmers for the 2021 season: SYP 1,150 for a kilogram of wheat and SYP 850 for barley ($0.37 and $0.28 respectively, at the parallel market exchange rate).

This came a few hours after another announcement, overturning Decision 119 issued on May 17, in which the AANES had more than doubled the price of fuel (from SYP 150 to SYP 400 per liter of diesel, and SYP 210 to SYP 410 per liter of petrol).

However, riots in the Kurdish-held areas of northeastern Syria, which left at least one person dead, prompted the AANES to review and subsequently retract Decision 119 within 48 hours.

If implemented, Decision 119 would have significantly impacted the harvest by increasing the cost of machinery (tractors) and water pumping. Farmers are able to buy diesel at the subsidized price of SYP 180 per liter, but the quantity available is limited, and many end up purchasing fuel on the open market.

To cope with rising costs exceeding their expected income, many farmers leased out their land this season to livestock herders rather than planting it. Others turned towards alternative crops, expected to generate a better profit. “This has been observed a lot in the first agriculture settlement line (Amuda, Qamshli, Qahtaniya, Jawadia, Maabada, and Derik areas). Farmers turned to crops such as cumin and fenugreek in addition to legume plants such as beans and lentils,” the agricultural project manager added.

The impact on the Assad regime

The AANES estimates that approximately 450,000 to 500,000 tons of wheat will be harvested this year, down from 850,000 tons in 2020 and 800,000 tons in 2019.

An unprecedented number of people—12.4 million Syrians or 60% of the population—are now food insecure

“If we buy this quantity, [and considering our] reserves from last year, we will be able to provide seeds for farmers in the next year and enough flour for the mills and bakeries,” Baroudo assured.

Still, the reduced size of the harvest will directly impact food security in Syria. An unprecedented number of people—12.4 million Syrians or 60% of the population—are now food insecure, up by 5.4 million people since the end of 2019. Areas under the regime’s control are particularly affected, and a bread crisis is raging.

Every year, Damascus struggles to secure a sufficient supply of wheat, as the main production areas lie east of the Euphrates, beyond its areas of control. A war of prices has ensued between the Syrian regime and the Kurdish-led AANES, each trying to incentivize farmers to sell to them. Last year, the AANES raised the price of a kilogram of wheat from SYP 225 in April to SYP 315 in May. The regime responded by raising its price to SYP 400, after which the AANES banned the export of wheat from its region.

A collapsing exchange rate, low foreign currency reserves and a high degree of isolation resulting from international sanctions have made the regime an impotent trade partner.

On May 12, the Syrian regime allocated SYP 450 billion to the purchase of wheat, with the aim to secure 500,000 tons (down from 700,000 last year) for SYP 900 per kilogram.

This price, similar to the one fixed by the AANES, may not be enough to incentivize farmers. Even if it does, “we will not allow any materials to exit outside the Autonomous Administration areas,” Baroudo stressed, suggesting that the AANES will ban the transport of cereals out of its areas for the third year in a row.

In parallel, the regime is struggling to import anything into Syria, notably wheat. A collapsing exchange rate, low foreign currency reserves and a high degree of isolation resulting from international sanctions have made the regime an impotent trade partner.

Last year, after issuing several tenders which failed repeatedly, Damascus managed to import 675,000 tons of wheat from its Russian ally, according to the economic publication Syria Report. This year, the regime contracted 400,000 tons from Russia and expects to receive 175,000 tons still pending from last year’s contract.

Despite these announcements, the situation is grim and more shortages are feared. “This year foreshadows a humanitarian and environmental disaster that will affect agriculture, livestock, and fisheries, and in turn food security in general,” Baroudo warned.

As Syria stands on the edge of the summer harvest, the water crisis looms and its full consequences are still unclear.