Op-Ed: ‘Confession’ videos under torture: A integral industry of dictatorship

Producing coerced confession videos under torture or the threat of torture is one way repressive regimes “keep themselves in power and tighten their control over the people,” writes Mansour al-Omari.

1 July 2022

A quarter of a century ago, the United Nations adopted the Convention against Torture and declared June 26 the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, “with a view to the total eradication of torture and the effective functioning of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.”

Torture continues to be used all over the world, but Syria is a leading torturer in terms of the number of victims and ugliness of the methods used. Despite being a signatory to the Convention against Torture, since 2011 the Syrian regime has repeatedly used systematic and widespread torture, in an unprecedented and unparalleled way. It has also undermined efforts to address torture made by the UN, international and national organizations and countries of the civilized world.

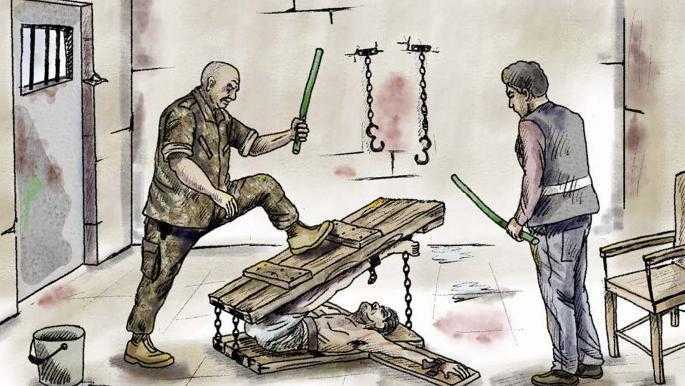

Repressive regimes use torture for many purposes, and in a variety of ways, to keep themselves in power and tighten their control over the people. One of these ways is producing confession videos under torture, or the threat of torture, to be used as incriminating evidence.

On March 21, Russian forces released Ukrainian journalist Victoria Roshchyna after detaining her on March 15 in Berdyansk, Ukraine. Russian intelligence compelled Roshchyna to appear in a video as a condition of her release, after she was beaten and humiliated, saying that Russian forces saved her life.

The independent Ukrainian media station Hromadske, which Roshchyna works for, posted on Twitter following her release, saying she would reveal the actual circumstances of her captivity at a later date. Given that the Russians knew Roshchyna would reveal the truth if released, what is the purpose of recording a video that would soon be debunked?

When Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, the “last and only dictator in Europe,” as he proudly calls himself, kidnapped journalist Raman Pratasevich in May 2021, the world saw how far a dictator can go to silence the press and opponents. Shortly after Pratasevich was arrested by Belarusian authorities, he appeared in a video clip, with bruises on his face, recounting his “confessions,” praising his treatment by the authorities, and expressing remorse for what he “did.”

In Syria, the Assad regime has exploited hundreds of false confessions by journalists, dissidents and others who did nothing but be arbitrarily detained and meet the conditions for a “good confession” video under torture.

Dictatorships, such as those of Assad, Lukashenko, Putin and others, use torture and the threat of it to produce confession videos for several purposes.

The fabricated videos serve both short- and long-term goals, including to promote the regime’s rhetoric to those loyal to it. They provide propaganda material, and are also used to support these regimes’ claims and to respond to accusations in international forums, including the halls of the United Nations, as Russia did in its campaign to distort the image of the White Helmets in Syria.

The videos serve these regimes’ false narratives, and they use the confessions forcibly extracted in them as evidence in their courts, in violation of the right to a fair trial guaranteed under international law, including the binding International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which Syria acceded to in 1969.

The videos may contain forced confessions and false allegations, in addition to fake testimonies by paid actors, loyalists or government employees.

In 2014, I met a journalist who worked for the Syrian regime’s Addounia TV channel before 2013. He described to me the process of producing one fabricated video, which he himself participated in. The security services summoned a journalist and photographer to prompt a woman, cooperating with the intelligence services, to say she was raped by Assad opponents based on a written script.

Later, one of the journalist’s colleagues leaked the original, unedited video, in which the woman is shown laughing and blaming her on-camera stumbles on the script.

The team falsifying confessions and testimonies usually consists of: the victim, a member of the media in a regime institution, and security forces or the torture team.

Under the rules of a fair trial, none of these videos, or coerced confessions and testimonies, are considered valid unless the statements are made in such a way that it is clear the speaker was not tortured or threatened. Proving that requires transparency about the speaker’s interrogation and the conditions of detention and treatment. These must meet the legal conditions of detention, including providing detainees with access to family and lawyers, ensuring their safety and that they are not subjected to torture, threats, punishment, or cruel or degrading treatment.

In the video broadcast by state-run Belarusian channels last year, Pratasevich, who was detained when warplanes forced a civilian aircraft he was on board to land in the capital of Belarus, said he is in good health, and that he played a role in organizing mass protests in Minsk in 2020.

“Yesterday, I was arrested by officials from the Ministry of Internal Affairs at the national airport in Minsk,” Pratasevich said. “I can say that I have no health problems, including with my heart or any other organs.” He continued, saying “the attitude of employees towards me is as correct as possible and according to the law. I continue cooperating with investigators and am confessing to having organized mass unrest in the city of Minsk.”

The video showed a pack of cigarettes in front of Pratasevich, as an indication that the dissident journalist was being treated well, and could even smoke. Even so, there were bruises on his face.

The Assad regime has used the same scenarios and dramatic elements, focusing on good treatment to deny torture, confessing to the crime to reinforce the regime narrative, and admitting remorse. All this is sometimes preceded by lengthy preparations, including torture and promises to stop the torture or release the person who confesses.

The father of the Belarusian opposition journalist said his son’s language in the video was not normal, and that he was clearly forced to say what he said. This comment is consistent with what was said by the mother of Rawan, a Syrian child who was forced to recount sexual incidents and rape on Syrian television in 2013. Her mother stressed that her daughter was speaking unusually in the interview.

Rawan was detained at the age of 15 by the Assad regime because her father was a leader in the opposition Free Syrian Army (FSA). State media later broadcast an interview with her, violating her rights as a child and once again showing the ugliness of the Assad regime and its media institutions.

This past March, after Ukrainian journalist Roshchyna was released, she revealed that Russian intelligence forced her to read a script on camera, after she was subjected to enforced disappearance, beatings and humiliation.

In Syria, while I was detained by Air Force Intelligence in Mezzeh, then by the 4th Division, because of my work documenting human rights violations, I met a number of detainees who were tortured daily for hourse, then thrown into their cells in preparation for their confession in front of investigators, officials and cameras.

One time, a detainee came into the cell smiling, even though his face was covered in tears and his body was wet. He didn’t wait to catch his breath before telling me, smiling: “The officer told me I convinced him.”

How interrogators pick who will confess

After arbitrary arrests in a neighborhood that saw demonstrations or violent incidents, the jailers ask detainees about the smallest personal details: their life, work, place of residence, close and extended family and the political stances of any relative or friend. They then send these written details to the investigators, who in turn study them to choose the “most appropriate” detainee to be charged with the crime.

Detainees are severely beaten from the moment they arrive at the interrogation center (the “welcome party”). After that, the jailers introduce them to the investigator, who accuses them of specific crimes, then asks them about these alleged crimes in detail.

The detainees must answer as though they have committed the crime, but many have not mastered the “art of confession.” The investigator shouts “you haven’t convinced me,” and asks the executioners to keep torturing the detainee and return them to their cell. The detainee practices confessing day after day, and must convince whoever is listening that they committed the fabricated crime.

A number of Syrian activists and journalists have appeared in videos showing false confessions and testimonies coerced under torture and threat, aimed at serving the Assad regime’s lies. They include a video of the father of Dr. Amani Ballour, and videos of others supporting the Assad regime’s chemical attack narrative, as well as false confession videos such as those of journalist Ali Othman, journalist Shiyar Khalil, Maryam Hayed, and Hazem Wakid and many others, who have either been released or whose fate remains unknown to this day.

This article was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.