Premature births increase in northwestern Syria after earthquake

More than a month after the February 6 earthquake, its repercussions on pregnant women continue, doctors in Idlib say, with an increase in cases of miscarriage and premature births.

14 March 2023

IDLIB — The February 6 earthquake in northern Syria and southern Turkey left Juhayna al-Qasem, 35, and her family unscathed, save for some cracks in her home in Idlib city. “Neither my unborn child, nor anybody in my family was affected,” she told Syria Direct. At the time, she was six months pregnant.

But when a subsequent earthquake struck the region on February 20, al-Qasem went into labor. Her son, who was born prematurely and died 10 days later, was one of its youngest victims.

The 6.4-magnitude earthquake injured more than 190 civilians “with fractures, various wounds, fainting and the collapse of damaged buildings,” according to the Syrian Civil Defense (White Helmets).

When it struck, “my children and I went out into the street,” al-Qasem, who is a mother of four, recalled. “After, I started feeling pains in my back and abdomen. I didn’t know they were symptoms of childbirth.”

The next day, al-Qasem—a displaced person from the Saraqeb countryside village of Dadikh—went to the al-Zahrawi Hospital in Idlib city, but it was closed for repairs. She was sent to the Maternity Hospital, where she was immediately admitted to the delivery room to give birth. Her doctors told her the premature birth was due to “the fear I experienced because of the earthquake,” she said.

Miscarriage and premature birth

The devastating February 6 earthquake, which killed at least 3,697 people and injured 14,814 across Syria—including 2,277 killed and 12,400 injured in the northwest alone—was followed by hundreds of aftershocks. Each new tremor sparked fear and panic among the residents of impacted areas, including pregnant women.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), in a February 19 report, estimated that around 133,000 pregnant women in Syria were affected by the earthquake. In the impacted areas, “some 6,600 women will have pregnancy and childbirth-related complications over the next three months,” UNFPA said, highlighting the urgency of ensuring access to healthcare.

Before her latest pregnancy, al-Qasem had not conceived a child for six years. “When the pregnancy [test] turned out positive, I was overjoyed, but things changed and my joy turned into great sadness,” she said with a long sigh. Al-Qasem said she did not experience premature births in any of her previous pregnancies, and that she and her fetus were both in good health before the earthquake.

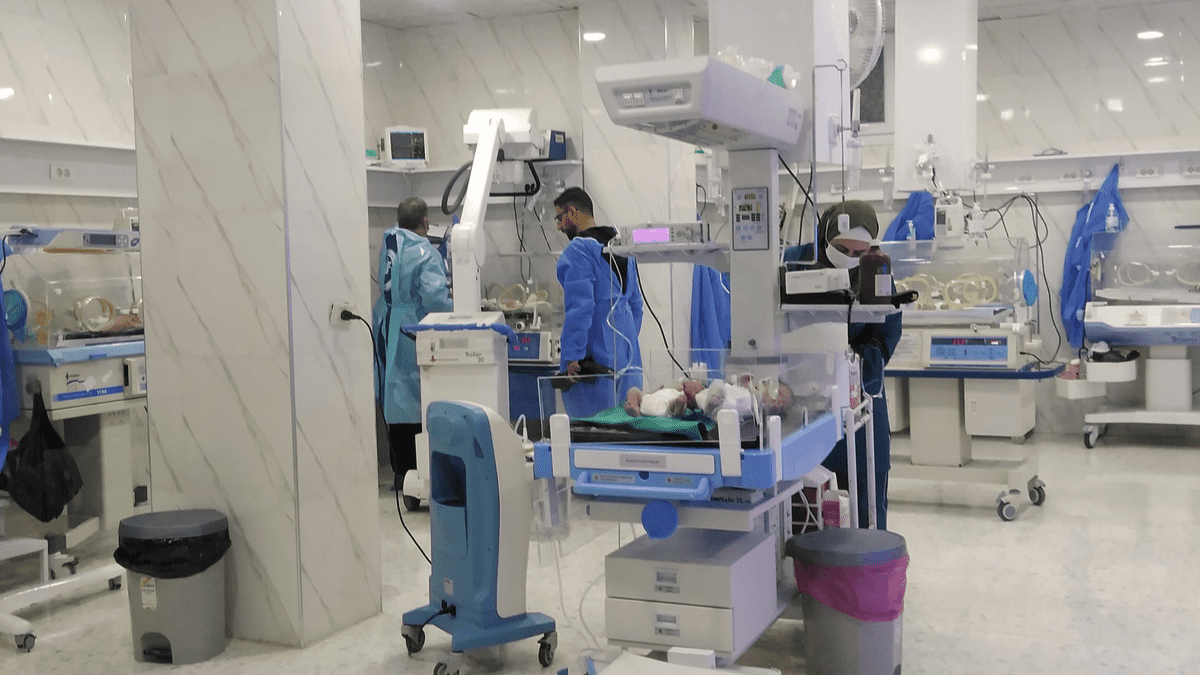

After she gave birth on February 21, “my baby was transferred to the neonatal unit and placed in an incubator,” suffering from “oxygen deficiency and weakness in his lungs, he needed a [blood] gas analysis daily,” al-Qasem said. Her child did not have any congenital disorders.

While al-Qasem was “suffering from the pains of childbirth,” her husband stayed at the hospital until after midnight every day to follow up on his son’s condition until the child “passed away 10 days later,” she said sadly.

In parts of northwestern Syria controlled by the opposition and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—home to more than four million people, more than half of whom are displaced like al-Qasem—“there were cases of premature births before the earthquake,” but they have since increased “by 15 percent,” explained Doctor Ikram Haboush, a gynecologist and head of the Maternity Hospital, which belongs to the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS).

Premature birth is defined as “every birth that happens after the twenty-fourth week and before the thirty-seventh week of pregnancy,” Haboush said.

“Pregnant women who are subjected to fear and terror are at risk of premature birth or miscarriage, so how about if the disaster is on the scale of the earthquake?” Haboush said. In addition to premature births, she noted there is an “increase in miscarriage and intrauterine fetal demise.” At the Maternity Hospital, “one or two cases of premature birth were recorded before the earthquake, which became three or four cases [a day] after it,” she said.

Doctor Hasna Hamdan, who works at the Maternity Hospital, said pregnant women were the most impacted by the earthquake. “The fear greatly affected them, leading to an increase in the number of cases of fetal heart failure, and in some cases bleeding, which led to miscarriage of the fetus and cases of cesarean scar rupture,” she said.

Al-Haboush and Hamdan’s statements were consistent with a report compiled by Batool al-Khodr, the head of reproductive health at the Idlib Health Directorate, a copy of which she provided to Syria Direct. It noted that “around 1,061 pregnant women were impacted by the earthquake in northwestern Syria, 711 premature births took place, and about 130 births by emergency C-section.”

According to al-Khodr’s figures, the number of cases of gestational bleeding—threatening premature birth and miscarriage—reached around 220 cases in northwestern Syria after the disaster.

Fragile medical sector

The February 6 earthquake highlighted the frailty of northwestern Syria’s medical sector, including gynecology and obstetrics units. It also damaged a number of hospitals and neonatal incubators.

Three hospitals went out of service due to the earthquake, al-Khodr said, including the Jenderes and Dana hospitals. Four others were damaged, “but are still working,” she told Syria Direct.

“The Salqin Obstetrics Center has stopped working, as well as the Dana Hospital, and we urgently need delivery tents in both areas,” she said. There is also “a shortage of clean delivery kits and sterile operating kits even in primary care centers,” she added. “We also need medicine outside the kits (anesthetics, antibiotics, pain relievers, labor suppressants and antispasmodics).”

She stressed the need to “secure support to set up mobile clinics in the earthquake-impacted areas, and fuel support for generators,” in addition to “support for an oxygen generator, after support for it was stopped by the [British] Human Appeal organization, and remains for only one in Idlib city.”

Read more: Women in northwestern Syria pay the price of donor fatigue

With increased numbers of premature births following the earthquake,“the incubators are filled with dozens of children born before their due date,” Haboush said, noting that “there are children we can’t provide incubators for.” The Maternity Hospital has 14 incubators, and “a baby may need to stay in one for up to two months,” she added.

She emphasized the need to “put the damaged hospitals and incubators in the earthquake-affected areas outside of Idlib city back into service as quickly as possible.” In those areas, a child could be born prematurely “and before reaching the Maternity Hospital in Idlib, have passed away.”

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.