Syria’s 2022 and the outlook for 2023

In 2022, Syria’s humanitarian, political and economic crisis reached new depths. How did the year unfold, and what can be expected in 2023?

15 December 2022

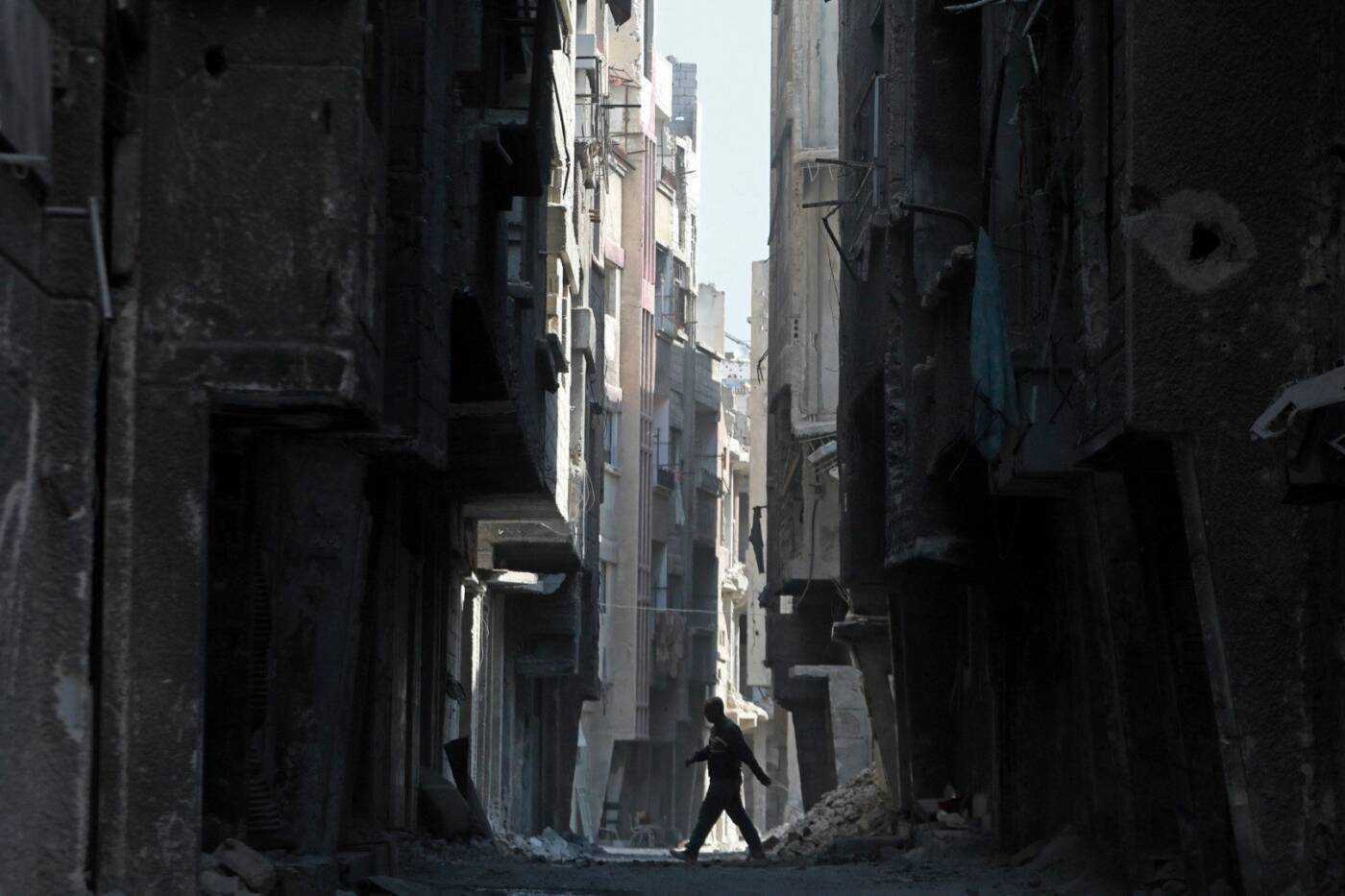

BEIRUT — In 2022, nearly 12 years into the Syrian uprising-turned-civil war, the country’s humanitarian, political and economic crisis reached new depths.

Cash-strapped Damascus is turning the country into a narco-state, a territorially defeated but persistent Islamic State (IS) continues to launch insurgent attacks and international steps towards normalization with the Bashar al-Assad regime continue, if slowly. Frontlines in the country’s northwest and northeast are frozen, but volatile. And while Turkey has yet to follow through on months of threats to launch a cross-border offensive against the United States (US)-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a ground attack would have major implications for the shape of things to come in 2023.

The northeast

In Syria’s northeast, a vast area primarily controlled by the Kurdish-led SDF, but where the US, Russia, Damascus, Iran, Turkey and Turkish-backed armed groups all have boots on the ground, Ankara has repeatedly threatened a ground invasion since May. Over the same period, Ankara stepped up targeted assassinations of SDF and Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) leaders in Syria via drone and rocket artillery strikes.

In November, a bombing in Istanbul brought the prospect of military action closer. Turkish authorities accused the SDF and PKK of committing the attack—which killed six people and injured 81—and launched days of airstrikes and shelling across northeastern Syria and Iraqi Kurdistan.

“Turkey’s air campaign has proven an effective tool for precision strikes on PKK cadres and constraining the ability of the SDF’s command structure to operate in the open. Whether that will prove to be enough for Erdoğan remains to be seen,” said Charles Lister, the director of the Middle East Institute’s Syria Program.

The possibility of a Turkish offensive in 2023 seems solid, several experts said. “It’s highly likely that there will be an operation,” said Gregory Waters, an analyst at International Crisis Group. “Tal Rifaat [an SDF-held town in northern Aleppo] is the most likely, more than Manbij or Kobane.”

“Until the spring, Erdoğan simply has to demonstrate a resolve to further constrain the SDF and, ideally, to secure an expansion of the ‘buffer zone’ across the north. For now, that means Tal Rifaat, Kobani and Manbij are under the target-set, but this doesn’t necessarily guarantee a ground incursion,” Lister said.

Elizabeth Tsurkov, a fellow at the New Lines Institute, agreed the risk of a Turkish invasion is “quite significant,” but explained that “Turkey’s adversaries in Syria are all opposed to this offensive, whether it’s Iran, Russia or the US.”

Facing Turkish threats, the SDF, long the main partner of the US in anti-IS operations in Syria, hinted at talks with Damascus throughout 2022. “The SDF has always been willing to talk to Assad’s regime,” but the group “is unlikely to prioritize the Damascus track,” Lister said. However, the “credibility of proponents within the SDF who support working with Damascus is likely growing by the week right now,” he added.

SDF moves towards Damascus have gone beyond talk alone. In July, aiming to protect its areas of influence from an anticipated Turkish offensive, the SDF announced an alliance with the regime that resulted in the establishment of joint military operations rooms and brought additional regime forces into SDF areas. Regime forces have been deployed in these areas since 2019, when the SDF asked Damascus for reinforcements during Turkey’s previous cross-border Operation Peace Spring.

But the US presence in northeastern Syria remains a key factor in the SDF’s calculations. “As long as the US is there, the SDF won’t give into Damascus’ demands, but Damascus is willing to wait out the SDF,” Waters explained. In 2023, under the Biden administration, no significant change is expected, but “the regime is playing the long game,” he said.

Islamic State

In 2022, IS continued to demonstrate that, despite the group’s loss of territorial control in Syria, it still poses a threat.

In northeastern Syria, IS cells carried out 262 attacks, killing 313 military personnel and civilians, according to the Rojava Information Center (RIC). Almost half of those deaths were registered in the group’s nine-day attack on al-Sinaa prison, which held 3,000 IS prisoners and 700 children with ties to the group, in Hasakah city in January.

For 2023, Waters foresaw a similar threat level, with “fluctuating but constant pressure” through sleeper cell attacks, and “at least one really significant attack—or attempted attack—in the northeast.”

This year, IS lost two of its leaders: A US raid killed Abu Ibrahim al-Qurashi in Idlib in February, and his successor, Abu al-Hassan al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, died during anti-IS operations by former Free Syrian Army (FSA) fighters in Daraa in October. The deaths may be a blow to the organization, but Water argued that at the current level of IS insurgency, the extremist group is not in crucial need of “senior level direction” as it focuses on “training, recruiting, lower-level financial operations and laying the groundwork for breaking local trust in the SDF and PYD [Democratic Union Party] institutions.”

Meanwhile, the aftermath of IS territorial control continues to be felt in the SDF-run al-Hol camp—where 53,845 women and children with ties to the organization remain in limbo, including nearly 8,000 third-country nationals—as well as al-Roj camp, which holds more than 5,000 women and children. In 2022, 511 women and children linked to IS were repatriated, according to RIC figures. Since 2019, Kazakhstan, Russia and Uzbekistan have repatriated the largest number of their citizens held in the camps.

The northwest

In 2022, no major frontlines changed in northwest Syria but there were several episodes of major infighting between Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) factions. In October, the Islamist fundamentalist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) intervened in intra-SNA fighting and pushed outside its base in Idlib and into SNA-held Afrin and beyond, before Turkey intervened to de-escalate.

If Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) prevail in the upcoming June 2023 elections, the country’s engagement in the northwest will likely continue. But a loss in those elections could impact Turkish foreign policy in Syria.

“There’s cause to be concerned about a [Republican People’s Party] CHP victory,” Waters said. The Turkish opposition has promised less intervention in foreign conflicts, a stance that might change once they “are briefed” on the “military security realities” of northwestern Syria, he added. Any Turkish withdrawal could lead to “a massive new refugee wave into Turkey and an expansion of PKK’s presence.”

For the Syrian regime, the northwest remains the last pocket outside its reach. “While conflict lines with the regime in northwestern Syria may have been frozen for several years, the region remains on a knife’s edge and a dramatic destabilization would threaten a major run on the Turkish border by millions of displaced people,” said Lister.

One of the key pillars of Erdoğan’s Syria policy is to prevent an influx of refugees, a likely scenario if any regime offensive were to take place. “While the AKP has been talking about re-engaging Assad’s regime, the enormous potential influence of northwestern Syria will ultimately trump any considerations about Damascus,” Lister said.

Humanitarian crisis & UN aid in the spotlight

In July, the United Nations Security Council renewed a resolution authorizing cross-border humanitarian aid to Syria through the Bab al-Hawa crossing in Idlib, despite concerns about stonewalling by Russia. The cross-border aid mechanism, a lifeline for millions of Syrians who rely on humanitarian aid, faces another renewal vote in January 2023.

In 2022, 14.6 million Syrians were in need of humanitarian aid and 54 percent were food insecure. The Syrian pound continued its plunge, and shortages of electricity and fuel were commonplace across the country. A cholera epidemic linked to contaminated water sources spread widely, infecting more than 35,000 people and, at the moment of publishing, killing at least 92.

Against the backdrop of Syria’s worsening humanitarian crisis, the UN aid sector faced allegations of corruption and lack of transparency. The WHO Syria representative came under fire in October for allegedly misspending funds and signing contracts with high-ranking Syrian regime figures.

The same month, an investigation into the top 100 UN suppliers in Syria by the Syrian Legal Development Program (SLDP) and the Observatory of Political and Economic Networks (OPEN) revealed that 23 percent of procurement funds went to companies with owners under Western sanctions. The same report found that 47 percent of funds were awarded to human rights abusers, including Desert Falcon LLC, a company co-owned by the leader of the National Defense Forces (NDF) militia in Damascus, whose forces carried out the 2013 Tadamon massacre.

Returns

In 2022, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) documented 43,254 returns to Syria, which add to the total of 346,387 returns recorded since 2016. Pressure for Syrian refugees to return spiked in Lebanon and Turkey, amid a rise in hostility and discriminatory attacks in both countries.

Turkish authorities deported hundreds of refugees, in some cases forcing them to sign voluntary return forms according to Human Rights Watch. Refugees have become a wedge issue in the upcoming 2023 elections, and earlier this year Erdoğan reiterated plans to return one million refugees to northern Syria.

Tsurkov expected deportations to continue in 2023. “Erdoğan is presenting these deportations as proof of the success of his policy. Supposedly, Turkey created this safe zone in the north [of Syria], that is allowing people to voluntarily return,” she said, calling into question the voluntary nature of these returns.

In 2022, Lebanese authorities resumed their cooperation with Damascus to coordinate organized voluntary returns, which were paused at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since October, more than 1,000 refugees have returned to Syria from Lebanon through organized returns.

Many returnees sought to escape economic devastation that has also driven Syrians to try to reach Europe by crossing the Mediterranean Sea from Lebanon. In 2022, two fatal shipwrecks on the route killed 141 people.

Accountability

The year 2022 began with a verdict in the landmark Koblenz trial, in which Anwar Raslan, the former head of the investigation unit at a notorious Syrian regime detention center, was convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life imprisonment by a German court.

The case was one of more than 28 Syria-related cases being pursued in domestic European courts under the legal principle of universal jurisdiction. Prosecution through the International Criminal Court or the creation of an ad hoc tribunal through the UN is blocked by Russia and China.

In terms of corporate accountability, the Paris Court of Appeals upheld the indictment of French company Lafarge for financing terrorism and complicity in crimes against humanity committed by armed groups in Syria. The company also pleaded guilty in a US court to financially supporting IS and paid a fine of $777.8 million.

In August, in response to years of efforts by family members of Syria’s missing and forcibly disappeared people, the UN Secretary-General recommended establishing an international mechanism to uncover the fate of Syria’s missing. Now, it is left to the UN General Assembly to vote on the establishment of this new entity.

And despite expectations that the International Court of Justice could decide in 2022 whether or not to open an investigation into the Syrian government for gross human rights violations, as requested by the Netherlands and Canada, the court has yet to make a determination.

Normalization

In 2022, several states took further steps towards normalizing ties with Damascus. The United Arab Emirates hosted Assad in his first visit to an Arab country since 2011, Bahrain restored its full diplomatic mission in Syria, the Palestinian militant group Hamas resumed relations with Assad and Algeria’s foreign minister visited Damascus. Yet, despite some talk of Assad returning to the Arab League summit in November, that did not happen.

Erdogan announced in December he had proposed a trilateral mechanism with Putin and Assad to “revisit long-strained relations” with Damascus. Previously he had hinted at normalization with Damascus this year, but Karam Shaar, a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute, called Ankara’s rhetoric “purely political posturing.”

Italy’s far-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni expressed support for Assad after she was elected in September, but has taken no concrete steps towards normalization. Shaar recognized “minor moves” by some European states but said they were “not significant,” and did not foresee any sea change in the “direction for the [European Union] EU as whole.”

Shaar did not anticipate meaningful steps towards normalization, as “those that have tried to do so, Jordan for instance, have come to believe that it was a mistake.” Even Russia and Iran “are pulling back gradually in terms of economic support to the regime” due to Assad’s unwillingness “to give any meaningful political concessions” that could lead to a lift of sanctions and reconstruction, he argued.

In November, after a 12-day visit to Syria, Alena Douhan, a UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and unilateral coercive measures urged that international sanctions on Damascus be lifted, saying they were exacerbating the “destruction and trauma suffered by the Syrian people since 2011.” In response, the Syrian Network of Human Rights said the rapporteur should instead “demand that the Syrian regime ends its violations and crimes against humanity.”

In 2023, Tsurkov expected that, “with the deterioration of the situation in Syria in terms of livelihoods” it is “possible that these calls [to lift sanctions] will emerge from time to time, but not in a way that will affect the discourse or policy,” given that the “prospect of getting anything in return for this sanctions removal is nonexistent.”

Narco-state

Under sanctions and with an economy in a seemingly endless downward spiral, cash-strapped Syria has become a narco-state. Syria’s biggest export is captagon—a type of amphetamine sometimes referred to as “poor man’s cocaine.” In 2020, the illicit industry’s estimated value was $3.46 billion, which grew to $5.7 billion in 2021. In 2022, that value nearly doubled, reaching an estimated $10 billion. This past April alone, $500 million worth of Syrian captagon was intercepted in neighboring countries.

The 4th Armored Division of the Syrian Army, commanded by the president’s brother, Maher al-Assad, is one key player in a broad range of criminal networks—reportedly including armed opposition groups and Iran-backed militias—involved in smuggling captagon towards the Gulf, North Africa and southern Europe via maritime and land routes through Lebanon, Iraq and Jordan. Deadly clashes at the Syria-Jordan border between Jordanian border forces and drug traffickers intensified in 2022.

Across the border in Druze-majority Suwayda—which is controlled by the regime but has a type of unofficial autonomy—local factions clashed repeatedly with those they described as Damascus-backed gangs. The factions accused these groups, some of which carry security credentials issued by Syrian military intelligence, of involvement in assassinations, abductions for ransom and the captagon trade. The deadliest clashes in Suwayda, in July, left 17 people dead. More recently, Suwayda residents protested in early December over economic hardship and increasing fuel and electricity shortages.