The agony of absence: Wives of disappeared detainees face uncertainty, social pressures

AMMAN: For more than four years, Umm Malak has held […]

9 October 2017

AMMAN: For more than four years, Umm Malak has held on to the hope that her husband Hussein is still alive, sitting in a darkened cell somewhere in Syria.

Hussein, then 32, was arrested by Syrian government forces on summer day in 2013 at a checkpoint in southern Damascus. A supermarket employee, he had been providing material support—food and supplies—to opponents of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, his wife says.

The summer day he was arrested, Hussein left his house in the town of Aqraba, southeast of the Syrian capital. He, his wife and their three daughters began living there several weeks prior after fleeing bombardment of the rebel-held al-Hajar al-Aswad district just south of Damascus.

Hussein was heading to the family home in al-Hajar al-Aswad. He kept birds on the roof there, and periodically returned to give them food and water. That day, he planned to set them free. As bombings increased and the security situation in and around the capital deteriorated, he was not sure he would always be able to reach and care for them.

What Umm Malak knows about what happened next—as related to her later by a 15-year-old neighbor who witnessed the arrest—is that a masked man pointed out her husband to state security forces at a checkpoint leading into al-Hajar al-Aswad. The men put Hussein in a car and took him away to an unknown location.

Umm Malak, 36, has received no news of her husband since she learned he was taken.

“My feelings tell me that he is still alive,” she tells Syria Direct from the apartment in Amman that a charity pays for her and her daughters to live in. The family shares the apartment with another Syrian refugee—a widow.

“I’ve searched and searched for him, but come up with nothing,” says Umm Malak. Some people in her situation pay lawyers and government officials for confirmation of whether detained loved ones are alive or dead, but she hasn’t done so.

“It costs a huge amount of money, and there is no guarantee that the answer I received would be true,” she says.

Umm Malak’s friends and acquaintances talk, whispering that after more than four years with no news, it is unlikely that her husband is still alive. But without proof one way or the other, she holds on to hope.

For friends and families, disappeared detainees exist in a space between life and death. Prolonged absence forces a difficult choice—assume loved ones to be dead and move on with life, or wait, perhaps for years, in the hope that they are still alive.

For many women—the wives of the disappeared and detained—that choice is particularly fraught. To divorce an absent spouse—even one presumed dead—and remarry can bring accusations of betrayal and abandonment from extended family, in-laws and society. To remain alone and wait may demonstrate loyalty, but also brings increased scrutiny and judgment from society as a single woman or female head of household.

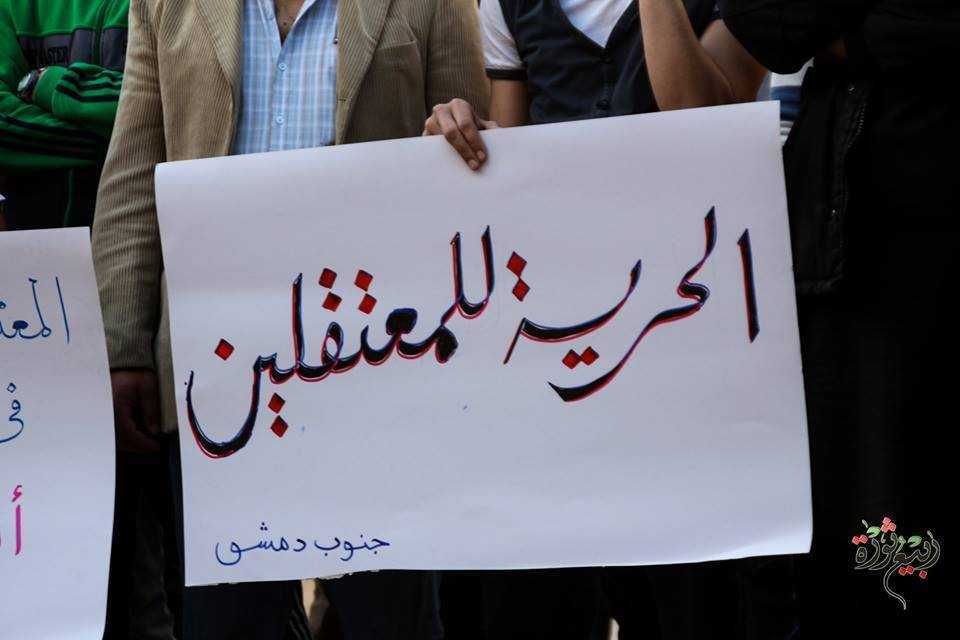

An estimated 92,000 detainees are currently held by Syrian government forces as of this year, according to the UK-based violations monitor Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR). Among them are more than 76,000 victims of enforced disappearance since March 2011, according to an August 2017 SNHR report.

Enforced disappearance, according to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, is the “arrest, detention or abduction of persons by, or with the authorization, support or acquiescence of, a State or a political organization, followed by a refusal to acknowledge that deprivation of freedom or give information on the whereabouts of those persons.”

Since Syria is not a member state of the Rome Statute, the country is not within the International Criminal Court’s jurisdiction.

What enforced disappearance means in Syria is that more than 76,000 people with lives and hopes and loved ones who were detained—at protests, at checkpoints, in their homes and on the street—have vanished.

The first news following a disappearance may take the form of a phone call from a prison official telling relatives that their loved one is dead, and asking them to come collect their identification documents.

Others eventually find them online, among the thousands of grim photos of the starved, beaten bodies of government detainees smuggled out of Syria in 2014 by a military defector codenamed “Caesar.” Some look through the 28,000 grim images and still come up empty-handed, a bitter relief.

Many times, detainees who knew the person are released and give loved ones the news that their sister, brother, mother, son has died.

But thousands of others still do not know what has happened.

The “ongoing and daily agony” of these family members, according to an August 2016 SNHR report on detainee disappearances, is particularly deep for “wives, mothers and children who bear the greatest burden from an economic and social standpoint.”

Financially, this is because those who disappear may be the sole breadwinner for a family. Socially, the decision made by the wives of the missing to either wait—like Umm Malak—or divorce and remarry, is not just personal, but public, with social consequences.

“I have gone through a lot of suffering and condemnation from society,” says Umm Malak.

The experiences of two women who chose differently—Umm Malak, a single mother of three, and 24-year-old Naela Fayez, who obtained a divorce after hearing news of her husband’s death in prison and remarried—illustrate a few of those consequences.

Together, their stories show some of the challenges faced by the wives of disappeared detainees, whichever path they take: to wait and hope, or divorce and remarry.

‘My right to keep living’

Naela Fayez knows her ex-husband Ali is dead, she says. Neither she nor any member of his family has seen his body—or any trace of him—since he was arrested in 2012 at a government checkpoint in the south Damascus suburb of Babila.

Ali worked in construction and was on his way to work when he was detained and disappeared one morning, says Naela. He had attended local demonstrations against the government of Bashar al-Assad.

After her husband, the family’s sole breadwinner, went missing, Naela and her two young sons moved in with his relatives in Syria’s southern Daraa province. In 2014, with violence increasing and living conditions deteriorating in Syria, she fled with her sons to Jordan.

In 2015, Ali’s family in Daraa received a phone call from the al-Khateeb Branch of the Syrian government’s State Security in Damascus. A voice told them to go to the branch and collect Ali’s documents. The family understood from this directive that he was dead, likely killed under torture. No one from the family risked going to collect the papers, fearing a trap.

Naela believes that Ali is dead, but with no body, no proof and no closure, his family refuses to accept that. Stories and rumors of detainees believed to be dead who return years later give them hope.

Even so, one year after that fateful phone call, and four years after her husband went missing, the now 30-year-old mother of two boys went to a sheikh in Jordan who gave her a ruling allowing her to remarry another Syrian—her cousin. She then did.

“In the end, I am a human being,” says Naela. “It is my right to keep living. I will not stay trapped and waiting.”

According to Islamic religious law, which governs the marriages of Sunni Muslims including Naela and Umm Malak, a wife may be granted a divorce if her husband is missing and presumed dead for between two and four years, depending on the school of thought.

The question of how and when a wife may divorce an absent, presumed-dead husband and perhaps remarry is becoming increasingly important as the war continues and the fates of tens of thousands of missing Syrians remain unknown.

In September 2017, the opposition Syrian Islamic Council, based in Turkey, issued a religious ruling defining procedures for separations and divorces for the wives of husbands who have been missing for a prolonged period.

The fatwa clarified that a woman may ask the court to issue a ruling as to the missing spouse’s death or absence and that she may remarry afterwards. However, should the missing husband return, any marriage in his absence would be annulled.

“If the husband is missing and nothing is known of his whereabouts, as in the case of a detainee, and he is thought most likely to be dead, then the wife must wait four years, then another four-month waiting period,” Abu Bakr, a religious judge in opposition-held Syria told Syria Direct earlier this year. “She may then remarry, without needing the permission of the court.”

The pro-government newspaper Al-Watan reported this past January that some 4,000 requests for separation or divorce had been registered in the state Sharia Court by wives of missing husbands in 2016.

But although Naela’s second marriage was religiously and legally permissible, her ex-husband’s family accused her of disloyalty.

“They attacked me, accused me of betraying him,” she says. “They completely reject my new marriage.”

Prolonged conflict with her former in-laws about her remarriage and what would happen to the children—under Islamic law they were to stay with her, but the family wanted them—sparked problems with Naela’s new husband. Ultimately, he refused to raise her children.

In the end, Naela sent her children to live with their father’s family in Daraa and shortly afterward moved to Egypt with her new husband.

“My heart burns without my children,” she says.

‘No matter how long his absence’

Umm Malak says she will wait as long as it takes for her husband to return. If Hussein is still alive, he is now 36 years old.

“I will wait for my husband no matter how long his absence,” says Umm Malak. “I won’t accept raising my daughters with any man but him. I will not divorce him and become another executioner, while he is suffering terribly under torture.”

But although Umm Malak has not chosen to remarry, she still says she faces intense social pressures and scrutiny.

As a single mother, Umm Malak says she is under a microscope, with community members scrutinizing every choice she makes. As the wife of a disappeared detainee, she is held to a high standard, any change in her life bringing “looks of suspicion and mistrust.”

“I am seen as a broken person, easily taken advantage of,” says Umm Malak, “especially by men.”

Fadel Abdul Ghany, the chairman of SNHR, emphasized the social impact of enforced disappearances on those left behind in the monitor’s August 2017 report.

“The mental, physical and emotional toll [that disappearance cases] have on the victims and their families make this crime a form of collective punishment against the community,” wrote Fadel Abdul Ghany.

As the years drag on, life continues. In Egypt, Naela lives with her new husband. In Jordan, Umm Malak raises her daughters as best she can under the gaze of prying, judging eyes.

Hanging over it all, Hussein’s absence is a deafening silence, an unfinished story about a country on fire and a man who left home to free his birds and disappeared into a void.

“My life is a prison of waiting,” she says.