Turkish strikes on energy infrastructure disrupt essential services, fuel pollution in northeastern Syria

Recent Turkish airstrikes and shelling damaged oil fields and power plants in SDF-held northeastern Syria, threatening a prolonged energy crisis and exacerbating widespread environmental pollution in the area.

30 November 2022

QAMISHLI, ERBIL — Sitting in front of his small house in the village of Mashoq, in Syria’s northeastern Hasakah province, Abu Fahd worried about the state of his village after Turkish shells hit a nearby power transformer and oil field.

“Both electricity and water have been cut off since, because the village well isn’t connected to a generator, but to the electricity grid,” he told Syria Direct on Sunday, nearly a week after the strikes.“We have one barrel of drinking water left, but no water left for the house, and no water for the animals,” Abu Fahd lamented. “The whole village depends on this well.”

The 56-year old farmer, whose land lies along the Syrian-Turkish border, had been living in fear of a Turkish attack for months. “We have around 15 hectares near the border that we couldn’t farm this year because of tensions with Turkey,” he sighed.

Mashoq lies within territory held by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been threatening since May with a ground offensive to create a “security belt” along the border. On November 20, Turkey launched a military operation targeting parts of northern Syria and Iraq, conducting dozens of airstrikes and shelling a wide array of targets over the course of a few days.

The operation, dubbed “Operation Claw-Sword,” was a direct response to a bombing in central Istanbul on November 13 that killed six people and injured 81. Turkey said the attack was carried out by the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) and the SDF, both of which deny responsibility. Turkey considers the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), the main component of the United States-backed SDF in northern Syria, to be an extension of the PKK, listed as a terrorist organization by Turkey and the US.

Turkey’s most recent airstrikes and shelling targeted PKK leadership in exile in Syria and Iraq, as well as the YPG and some Syrian government forces. Ankara has previously assassinated dozens of members of the YPG through targeted drone strikes in Syria.

But in addition to military targets, Turkish bombardment since November 20 struck civilian infrastructure, according to local media and human rights monitors. Sites hit included a COVID-19 treatment center, grain silos, power transmission stations, oil fields and a gas station.

By targeting energy networks, the Turkish army appears to be trying to cut off the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), which administers SDF-held territories, from its lifeline—oil production. But the strikes have also left thousands of civilians without electricity, water and heat. And when sites such as oil fields are hit, the danger is not only the short-term impact on civilians’ lives, but long-term effects on health through environmental pollution.

Abu Fahd talks about the aftermath of the Turkish strikes on his village of Mashoq, Hasakah province, 27/11/2022 (Solin Muhammed Amin/Syria Direct)

An energy crisis

“Through these strikes, Turkey is trying to destroy the energy infrastructure of the region,” Rasha Abbas, the co-chair of the AANES’ Office of Energy for the Jazira region, which roughly corresponds to Hasakah province, told Syria Direct. “They have targeted the [Suwaidiyya] gas plant, which feeds all of northeastern Syria, producing around 13-14,000 gas cylinders per day for domestic use.”

The shelling of power stations and oil fields has cut off water services in some localities as pumps and purification stations came to a halt without electricity.

In addition, “strikes against power transformers, oil stations and other energy infrastructure caused a power outage in 17 villages around al-Qahtaniya (Tirbespî),” Muhammad al-Mahmoud, a worker on the Mashoq oil field, told Syria Direct. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), a human rights monitor, blackouts left thousands without electricity in the cities of Qamishli and al-Malikiyah (Derik), increasing reliance on fuel-powered generators.

In parallel, oil fields also came to a standstill across most of the oil-rich Hasakah province. In Mashoq alone, “four wells out of seven stopped working following the shelling,” al-Mahmoud added, pointing towards blackened tanks and pipes.

Muhammad al-Mahmoud examines damage at the Mashoq oil field in Hasakah province, northeastern Syria, 27/11/2022 (Solin Muhammed Amin/Syria Direct)

“The losses are large and in the millions,” Abdul Latif Ahmed, an administrator at the Oudeh Petroleum Company, an AANES-affiliated company managing oil fields in Hasakah, told Syria Direct on Thursday. He requested a pseudonym because he is not authorized to speak with the media. “More than 20 oil production sites and subsites have been struck.”

Speaking from another oil field near al-Qahtaniya that was recently hit by a mortar shell, Ahmed said production—which is normally 400-to-600 barrels a day on this field—completely stopped following damage to two oil tanks. “We have the means to repair the field,” he said, “but we don’t plan to do it for now because it could be targeted again.”

Attrition and pollution

As winter sets in, damage to fuel infrastructure and power stations will likely drive up the price and availability of heating across SDF-held parts of Syria. It is also a blow to the AANES’ main source of revenue.

Crude oil exports to Iraqi Kurdistan and regime-held parts of Syria enable the AANES to run essential services and pay the salaries of SDF fighters. “Turkey’s attacks are likely a signal that they can put serious efforts into denying the Self Administration [AANES] from generating income from fuel sales,” said Wim Zwijnenburg, a Programme Leader at the NGO Pax for Peace who has conducted several studies on the environmental impact of war in Syria.

In addition to oil fields extracting crude for export, the Jazira region is dotted with informal refineries that generate low-quality diesel fuel for the local market. These refineries—which popped up as an alternative to damaged formal oil infrastructure during the war—have long been a major source of pollution across Syria, resulting in “local oil spills and years of oil dumping into local rivers and creeks, while the absence of proper oil waste management and professional refineries is causing serious air and soil pollution,” Zwijnenburg said.

Oil residues from informal refining contaminate the surrounding soil, as seen around these recently closed refineries in the north of Hasakah province, 11/10/2022 (Lyse Mauvais/Syria Direct)

Oil-related pollution has long been linked to high rates of cancer, respiratory illnesses and birth defects across northeastern Syria, officials from the AANES Ministry of Health told Syria Direct in October. In recent years, the de facto authorities have made limited but growing efforts to regulate the industry, outlawing child labor at refineries and banning the most rudimentary types of furnaces from operating.

But Operation Claw-Sword could upend these efforts, increasing the need for maintenance and repair of damaged infrastructure, as well as for cleaning up localized spills. And with some of the area’s larger oil facilities out of operation, some of the shuttered informal refineries could open up again.

“The current strikes seem to have limited impact, mainly leading to localized air pollution and potential soil and water pollution, but due to lack of sufficient equipment and capacity for remediation, clean-up and repairs could take a long time, worsening existing pollution and risking wider collapse of oil infrastructure,” Zwijnenburg said. “There are over 1,000 kilometers of outdated oil and gas pipelines in northeastern Syria that need replacing, at least 20 clusters of makeshift refineries still operational in Hasakah and over 12 crudely constructed oil waste dumps.”

A widespread crisis

International humanitarian law prohibits parties at war from targeting civilian infrastructure— including energy infrastructure—except if used for a military purpose, in which case evidence should be provided to justify the strikes. Additional Protocol I to the Geneva convention also specifically outlaws “methods or means of warfare which are intended, or may be expected, to cause widespread, long-term, and severe damage to the natural environment,” as can be expected when targeting oil fields.

But around the world, belligerents have so far shown little regard for these provisions, for which it has been difficult to seek accountability in international courts.

“Under current international law, there are serious lacunas when it comes to state responsibility for environmental damage, as the threshold for accountability is really high, namely the damage must be severe, long-term and widespread at the same time,” Zwijnenburg said. “Small spills in the case of northeastern Syria wouldn’t [meet this criteria], even the long-term damage to the local environment from dumping oil waste wouldn’t.”

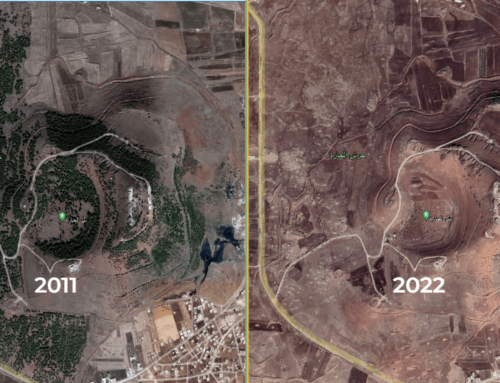

The latest strikes against energy infrastructure fall within a wider pattern witnessed time and again in Syria since 2011, as parties on all sides of the war weaponized energy infrastructure.

In 2015, the Aleppo Thermal Plant, one of the country’s main power stations, was heavily shelled by the Syrian regime to cut off then-opposition-held parts of Aleppo city from electricity. In 2016, Idlib’s Zayzoon power plant was destroyed by regime shelling and then looted by Islamist groups. Together, the two plants accounted for 15 percent of Syria’s electricity production. The following year, a key power plant was destroyed in Deir-ez-Zor, this time by the US-led anti-Islamic State (IS) coalition. The international coalition has also targeted oil fields in the Syrian and Iraqi desert to deprive IS of revenue, leaving behind its own legacy of pollution.

As a result, Syria’s energy sector is in shambles. Many Syrians have grown accustomed to living on a few hours of electricity per day, queuing for hours in front of gas stations to fill their cars and battling cold winters with limited heating options. According to a 2021 assessment, Syrians today consume 15 percent of the state electricity they used to rely on prior to the war. Reliance on fuel-powered generators across the country has increased as a result, driving up air pollution due to the fumes they release.

Today, thousands of people in northeastern Syria who have been directly or indirectly affected by Operation Claw-Sword are trying to secure electricity, water and heating in the aftermath of the strikes. Disruption to energy services could still last for weeks or months, depending on the course of Turkey’s military operation.

But even after immediate needs are met, a slower moving disaster persists. The long-term environmental fallout of the war continues to grow, with repercussions that will last for years to come.

Oil residues around an informal refinery in the north of Hasakah province, 11/10/2022 (Lyse Mauvais/Syria Direct)