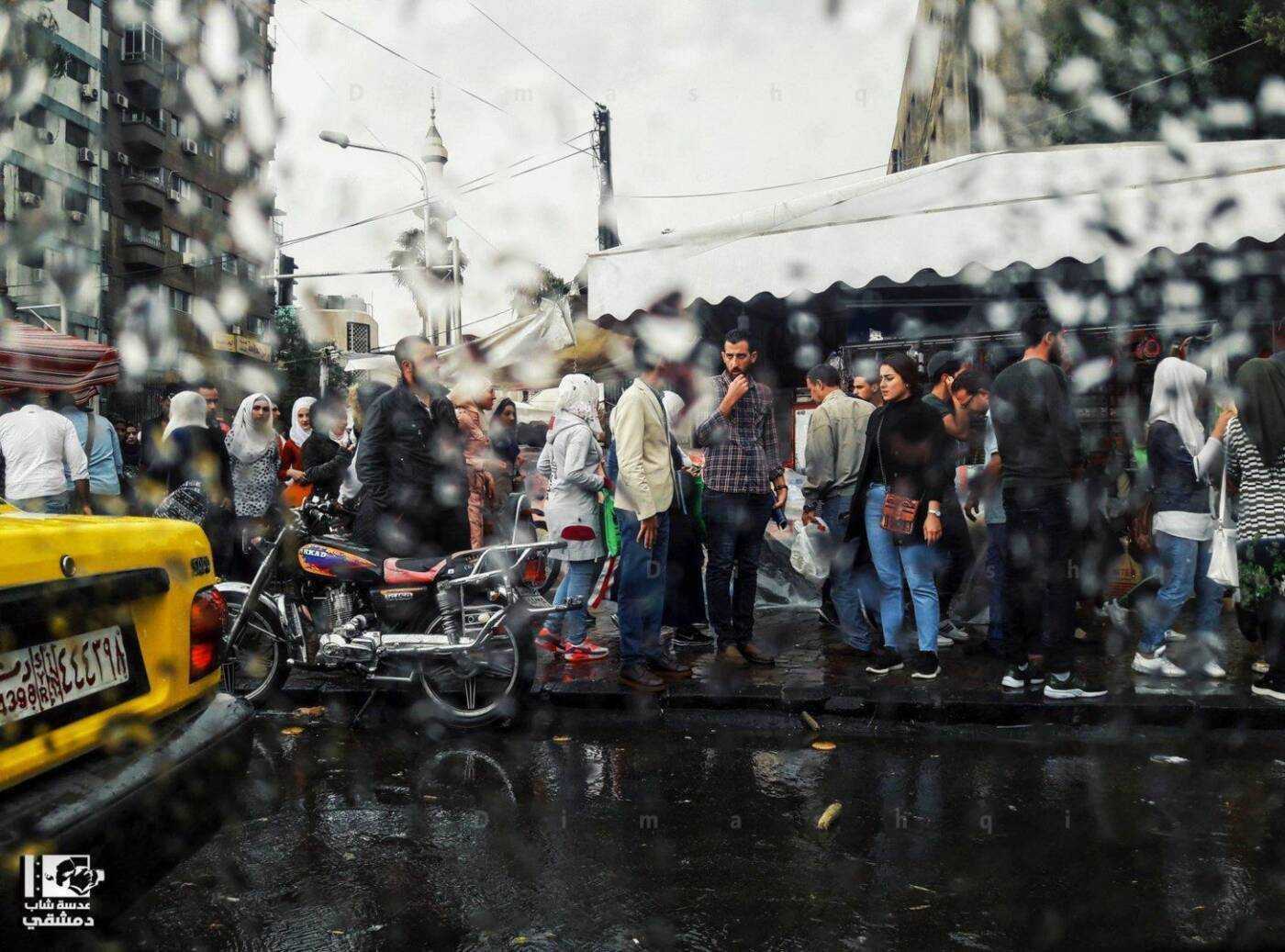

‘Waiting for a place in the gas line’: Residents of government-held Syria voice discontent over fuel, electricity shortages

Gas cylinders are distributed in the Sarouja neighborhood of Damascus […]

30 January 2019

AMMAN: In one video, a man marries a gas cylinder dressed in a white wedding gown and couldn’t be happier about it.

In another, a well-stocked gas truck cruises through town like a parade float, escorted by a fleet of motorbikes and taxis honking in celebration.

And in a meme shared to Facebook, a mythical god gracefully balances a gas canister on her head. “Gassius,” a caption reads, “the Syrian god of gas.”

Government-held Syria is reeling from an energy crisis this winter, and citizens are responding in turn—not with street protests but with videos, cartoons and memes that are making the rounds online, relaying a population’s frustrations as they go.

Syrians are struggling amid a severe shortage of gas cylinders—used across the country and much of the region to fuel stoves and, in many homes, to keep warm through wintry conditions and freezing weather.

The crisis, which has been blamed on everything from international sanctions and corrupt gas distributors to unusually high demand, has hit major cities stretching from Suwayda in the south to Alawite-majority settlements along the Mediterranean coast, and east to Deir e-Zor near the Iraqi border.

In Damascus and its outlying suburbs, a relative calm is increasingly touted by the government and its supporters as a sign that the war is now fading away. And yet residents have been left to face exceptionally long waits at infrequent gas distributions, prohibitive pricing and the subsequent need to cope with less-than-ideal alternatives just to get by. Syrians in formerly opposition-held areas of the capital, retaken one after the other by the government and its allies after 2016, have been hit hardest.

At the same time, insufficient electricity networks are providing only patchy service throughout the day, even in affluent areas of the city—challenging hopes that crippling power cuts and outages had finally come to end after seven years of war.

Long queues, steep prices

Before the latest shortages took hold, Damascus resident Yaman Abdullah’s* family of six would often go through one standard gas cylinder every 15 days.

Now, however, the family has been forced to start rationing. By cutting down on daily gas use for cooking, and by relying on sporadic electric heater use and blankets for heat, they make each cylinder last for at least a month.

At the same time, Abdullah, who has a public sector job in a government office, acknowledges that he’s better off than many. “It’s much easier for me than for others,” he tells Syria Direct.

“Don’t exchange me,” says the gas cylinder. The man replies, “Don’t worry, there’s no gas.” Cartoon courtesy of Wessam Jamoul.

Through his position, Abdullah says he’s able to register for gas from a specialized government agency, and then he waits about 20 days for the cylinder to arrive, costing him a discounted 2,600 Syrian lira (about $5).

If he’s able to pull some additional strings, the gas might come faster—five days tops.

But for ordinary Syrians in the capital without a public sector job, obtaining a cylinder—let alone paying for one—can be a feat in and of itself.

Prices often skyrocket past the official rate which, according to Abdullah, stands at 2,800 pounds (about $5.50).

And intermittent gas distributions take place in each of the city’s districts on only a handful of assigned days each month, with limited supplies leading to long queues and fierce competition. At some distribution points, lines have reportedly been divided in two: the first for soldiers, who get priority, and the second for civilians. Sometimes people simply go home empty-handed.

“You need to leave your home by 2 am, head straight to the distribution point and get in line,” Abdullah says. “I swear, there are people who are taking blankets and sleeping in the street just to get a spot.”

A video titled “Gas Invasion in Occupied Damascus,” courtesy of Fadi Shubat.

For those who can’t obtain gas through the official channels, the black market is often the last hope. Well-connected middlemen and supermarket owners-turned-gas-dealers now deliver canisters to homes or arrange for direct sales between desperate customers and those with surplus.

On the black market, the cost of a cylinder can reach 5,000 Syrian lira (close to $10), according to Abdullah. Other reports suggest the price goes even higher, sometimes doubling or even tripling the standard rate in parts of the capital and its outskirts.

“You’ve got to get gas using wasta [connections],” says 28-year-old student Radwan Ali, who lives in the southeastern Damascus suburb of Jaramana. “That’s if you can find it at all.”

“It’s 2019, and people in the capital are burning wood! Can you imagine?”

‘Back to the methods we used under siege’

While Damascus is often said to be a city no longer at war, residents in parts of the city recently recaptured from opposition or hardline Islamist groups are still living with the aftermath. Key infrastructure is in tatters, with electrical networks badly in need of mending.

And recent fuel shortages have battered residents of these areas that were, in many cases, working-class informal settlements before the outbreak of the 2011 uprising.

According to several residents, the practice of burning wood for household use is especially prevalent in those areas of Damascus since gas is even harder to come by there than in the city center.

In East Ghouta, besieged and bombarded for years by pro-government forces until rebels evacuated last spring, residents say they’re well accustomed to seeking out alternative heat sources.

During the winters under siege, East Ghoutans would burn whatever they could find on the streets—plastic, scraps of wood, garbage—just to stay warm amid chronic fuel shortages.

A cartoon shared on December 7, 2018, courtesy of Moayed Hussein.

Some had hoped things were going to change.

“Once state institutions returned to Ghouta, most people had high hopes that services would get better,” says 50-year-old Saher Abdulkareem, a mother of five in the East Ghouta town of Zamalka.

And while living situation has definitely improved because “there’s no siege or anything like that,” she adds, her first winter under renewed government control has tempered many of those expectations.

At the start of the season, Abdulkareem says many, herself included, eagerly purchased and set up diesel heaters to use in their homes.

But diesel has proven scarce in East Ghouta this winter, with most fuel stations in the agricultural pocket out of service.

So instead, Abdulkareem loads the chamber of her new diesel heater with wood and purchases electricity from privately owned generators, since the electrical network remains under repair.

“We’re going back to the heating methods that we used under siege,” she says.

Electricity supplies across the Syrian capital remain unreliable, according to residents, even back in the city center where the network had been fully restored in 2017, after years of paralyzing cuts.

For many Damascus residents, electricity often comes and goes several times in an average day: three hours on, three hours off. And, when additional outages take place, there might be only two hours of service in a 24-hour period.

“The electricity acts as a compass for our daily activities,” public sector employee Abdullah says. “You’ve got to arrange everything accordingly—heating, washing, ironing. And when there’s an outage, and no electricity at all, it screws up your entire day.”

The impact of cuts are being felt even in some of the most upscale districts of the capital—including al-Mezzeh in western Damascus, traditionally home to many of the city’s elite and government insiders as well as embassies, villas and UN offices.

“Electricity never used to go out,” 58-year-old al-Mezzeh resident Abdul Qader tells Syria Direct, “but recently, it’s been running for four hours and then cuts out for two.”

“They say it’s temporary. God willing, these issues will be resolved.”

‘Are you gonna cook for us?’

Seemingly under pressure from growing criticism and discontent across Damascus and beyond, government officials have put forward statements and plans in an effort to reassure the public that the crisis is being addressed.

Government officials have in turn blamed the current energy crisis on US sanctions for hitting the country’s oil trade—as well as on delayed deliveries of oil supplies, corruption, unusually high demand and cold weather.

Some of the proposals to fight shortages have included increasing daily production of gas cylinders, cracking down on illegal sales and rehabilitating damaged gas stations and oil fields. At the same time, officials have called on consumers to report distributors requesting unlawful prices.

In December, pro-government daily al-Watan reported that ships carrying supplemental gas supplies had arrived to the northwestern coast, ready for distribution around the country. “The bottlenecks occuring in Damascus…will be resolved by more than 80 percent in the next week,” an unnamed source from the Ministry of Oil was quoted as saying.

But more than a month later, pro-government media outlets are still reporting similar statements—although not everyone is buying it.

“There will be a significant breakthrough with gas distribution starting from the beginning of next week,” Mansour Taha, the government official supervising distributions in Damascus and its suburbs, was quoted as saying on the Facebook page for pro-government outlet Damascus Now on January 23.

Hundreds of the page’s 2.6 million followers were quick to respond in the comments below the post. Many laughed. Others were more direct in their criticism.

“Liar,” said one.

“We’ve been hearing this talk for a month now, Mansour!” said another.

“Starting from the summer, God willing,” read a sarcastic third response.

In a separate Damascus Now post last week, Syrian Prime Minister Imad Khamis was quoted as saying the government had “found alternatives to the gas crisis.”

Again, there were plenty of comments—often biting—as followers suggested their own “alternatives” to help solve the crisis.

“Extracting the gas from a Pepsi bottle.”

“A lifeboat.”

“Are you gonna cook for us at home or what?”

Several posts even included phone numbers.

“This is my friend’s number,” read one. “Gas distribution in Damascus. Only 3,100 lira, and delivery to your home.”

With little certainty on when actual alternatives are heading their way, or simply when the weather will warm up, those living in the capital and the surrounding countryside are preparing for the long haul.

“We’ve got to get used to the crisis, and only use gas when necessary,” says resident Abdullah.

“We’re between a rock and a hard place. Either we cut down, or we’re gonna sleep in the streets waiting for a place in the gas line.”

*All names have been changed to protect the security of interviewees.