‘We want accountability’: Family of Syrian refugee tortured to death in Lebanon fight for justice

The family of Bashar Abdel Saud, a Syrian refugee who died while in the custody of Lebanon’s State Security last week, is fighting for accountability in a ‘climate of impunity’.

7 September 2022

SHATILA – Last Tuesday, Hamda al-Said was having dinner with her husband Bashar Abdul Saud and their three children in their one-room home in Lebanon’s Shatila refugee camp when members of the camp’s security forces detained Bashar and handed him over to Lebanese State Security officials.

The next morning, Hamda woke up a widow.

Hamda learned of her husband’s death on Facebook, when she stumbled upon photos of Bashar’s bruised body. On September 3, four days after Bashar was detained and three days after his death, State Security called his family and told them to come collect his body. He was 30 years old.

The same day, a Lebanese judicial source told AFP that Bashar suffered a heart attack in custody three hours after his arrest. However, a video of Bashar’s body provided to Syria Direct by the family’s lawyer shows severe injuries. Deep bruises and cuts cover the entire back of his body, from head to toe.

For years, human rights organizations have documented how Lebanese security branches use torture to extract confessions, especially in drug or terrorism-related cases. In 2010, Lebanon became the first country in the Middle East and North Africa to ratify the Optional Protocol to the UN Convention Against Torture, and in 2017 the parliament passed the Anti-Torture Law (65/2017). Yet torture—fed by what survivors, lawyers and advocates describe as a climate of impunity—remains a reality in Lebanese detention facilities.

The precarity of Syrian refugees in Lebanon makes them one of the groups most vulnerable to mistreatment if detained by the authorities. Bashar’s death in custody last week sheds further light on the continued use of torture by Lebanese security forces.

‘It will be a couple of questions and we’ll bring him back’

In a dark alley of Shatila camp, in the outskirts of Lebanon’s capital Beirut, 29-year-old Hamda sat this week with her one-month-old baby on her lap. Basel, Bashar’s brother, turned on his phone lantern to light the dim room.

Bashar moved to Shatila eight years ago, when he defected from the Syrian army and fled from Syria’s eastern Deir e-Zor province to Lebanon. In Beirut, he worked as a porter and day laborer. Hamda stayed in Deir e-Zor, and would often visit Bashar in Shatila. In early 2021, she joined Bashar in Lebanon with their two sons, today seven and nine years old. In July, the family welcomed their third child.

At 8pm on August 30, the Palestinian security apparatus in Shatila came to the family’s home and detained Bashar. “When they took him, they didn’t tell us anything, they only told us it would be a couple of questions and they’d bring him back,” Hamda explained.

Mohammed Sablouh, a lawyer specialized in torture cases and the director of the Prisoners’ Rights Center at the Tripoli Bar Association, has taken on the family’s case following Bashar’s death. “State Security asked the Palestinian security to bring him without any arrest warrant, they tied his hands and stripped him of his clothes in front of the people in the street,” Sablouh explained.

The family learned from news reports that Bashar was taken to State Security headquarters in south Lebanon, and learned of his death on social media. “They took him on Tuesday, and on Wednesday was dead. He didn’t have any heart condition, and he wasn’t sick,” Basel’s brother Bashar said. “It is clear what happened—he died under torture.”

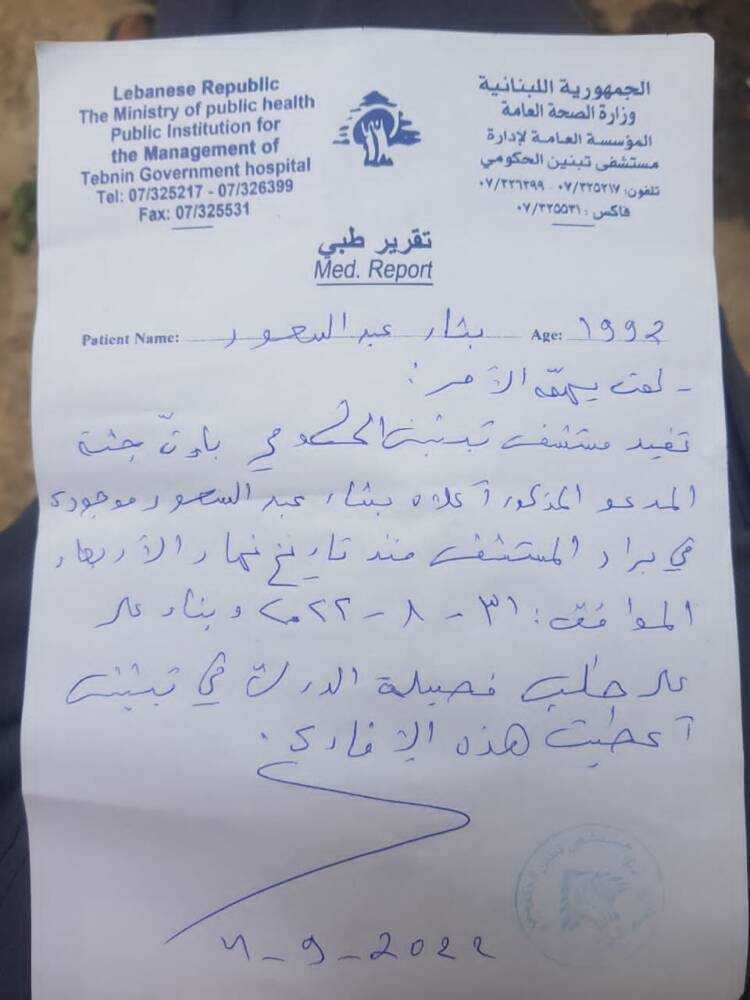

According to a medical report dated September 4 provided to Syria Direct, Bashar’s body was received by Tebnin Hospital in south Lebanon, near State Security headquarters, on August 31 at the request of security officials, and placed in the morgue.

A photo shows the medical report of Bashar Abdul Saud body being accepted at Tebnin Hospital at the request of State Security officials, 04/09/2022 (Syria Direct)

The family, at their lawyer’s advice, has refused to accept Bashar’s body until an independent forensic examination takes place that explains his cause of death and the nature of his wounds. “You detain him, you kill him and then you tell us to come and take his body? I don’t want his body, I want an autopsy, I want to know who detained him and killed him, and who gave his name to the State Security,” Hamda said.

“The signs of torture are very clear, now we’re waiting for this independent medical report,” Sablouh added.

A flurry of accusations

Basel Abdul Saud holds his phone showing a picture of his late brother Bashar, Shatila refugee camp, Beirut, 06/09/2022 (A. Medina/Syria Direct)

After photos of Bashar’s lifeless body began to spread on social media last week, State Security issued a statement accusing Bashar of forging a $50 bill and belonging to the Islamic State (IS). Lawyer Sablouh called the accusations baseless. “They said he had a fake $50 bill, that he sold drugs, that he was part of Daesh [IS]—they are just trying to cover their crime,” he said.

The Abdul Saud family maintains Bashar’s innocence. “They put these accusations on him just to justify themselves. Every hour they say something new: that he had forged money, that he had hashish, that he drank something and got on the nerves of the officer or that he was Daesh,” Hamda said. “They arrested, humiliated and killed him, and now they are trying to justify themselves.”

Concerning the charge of forgery, Hamda said the family is 20 million LBP (around $568 at the parallel market rate) in debt to cover electricity bills, groceries and baby formula. “If he was forging dollars, how could we be in such debt?” she asked.

Regardless of what charges led to Bashar’s detention, torture is a crime against humanity under international law, and is banned under Lebanon’s domestic law and international treaty obligations.

Basel and Hamda, still in shock at Bashar’s sudden death, want justice. “I saw the photo of how they tortured and cut him up. We won’t forget his rights; we want accountability,” Basel said.

“I’m going to fight for my husband’s rights,” Hamda added.

The legal battle ahead

The conditions of Abdul Saud’s detention violated Article 47 of Lebanon’s Criminal Procedure Code and Law 65. “They didn’t allow him to have a lawyer, didn’t inform his family where he was [being detained] and they didn’t allow him to contact his family,” explained Sablouh, who has presented a complaint to Lebanon’s General Prosecutor concerning these violations.

The case to investigate Abdul Saud’s death has been sent to the military court. Crimes committed by security personnel fall under the jurisdiction of Lebanon’s military justice system, but “when these crimes are committed in their capacity as judicial police, meaning that they’re conducting an investigation in a judicial case, crimes committed in these circumstances go to the regular court,” Ghida Frangieh, a researcher at Legal Agenda, a research and advocacy organization, explained.

Bashar’s case should be tried in a regular court according to Article 15 of the Criminal Procedure Code and Law 65. Sablouh plans to present a complaint before the General Prosecutor to refer the case to a civil judge.

Amnesty International has demanded the case to be referred to a civilian court to ensure transparency and impartiality. The main difference between a military and a regular court, is that in a military tribunal “the victims can’t participate to the investigation and they’re treated as witnesses,” Frangieh explained.

On September 3, Lebanon’s military prosecutor arrested five State Security officers for investigation into their role in Abdul Saud’s death, but Sablouh dismissed this move as a public relations stunt, one he has seen before. “We have a previous experience in a similar [torture] case where they were detained for 10 days, and then were just released,” he said.

Sablouh has little faith in military courts. “If I don’t see a fair trial where we find that truth and justice is achieved for this victim, I will take the case to international and European levels,” he said.

Despite many credible reports of torture in Lebanon since the country’s Anti-Torture Law 65 was passed in 2017, no security officials have been sentenced under the legislation. In 2017, Lebanese actor Ziad Itani was tortured in detention and filed a complaint against State Security. His case is still pending. “Not only were the officers that tortured Ziad Itani not held accountable, but they were rewarded by being promoted,” Frangieh explained, adding that “impunity kills, because had these officers been held accountable for the torture of Ziad Itani, they would have learned the lesson not to repeat it.”

Heba Morayef, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa said in a statement that “impunity for torture remains commonplace, with dozens of complaints regarding torture and other ill-treatment filed under the 2017 Anti-Torture Law rarely reaching court and most closed without an effective investigation.”

For Frangieh, the fact that the anti-torture legislation “remains largely unimplemented is encouraging further acts of torture that lead to death.”

No official has been punished in the five cases—known to the public—of death in custody following suspected torture in Lebanon in the past decade. In 2019, Lebanese citizen Hassan Dika died in Internal Security Forces custody. In 2017, four Syrians died in military custody in Arsal. And in 2013, Nader Bayoumi from Saida died in military custody. Bashar’ death would be the sixth case.

Sablouh blames not only Lebanese security forces for committing torture, but also the country’s judiciary. “It is the judiciary that bears responsibility for torture in Lebanon, because it has not fulfilled its role for years, and the [office of the] General Prosecutor bears a bigger responsibility because it is allowing, intentionally or unintentionally, the perpetrators of the crime of torture to go unpunished.”

“If there was true accountability for the crime of torture, these officers wouldn’t have dared to kill Bashar Abdul Saud,” Sablouh added.