What does the Chinese-brokered Saudi-Iran deal mean for Syria?

Besides bolstering normalization with Assad normalization, how might the Saudi-Iran deal affect Syria? Can Riyadh counter Iranian influence on Syria or push Assad to clamp down on the captagon trade? Will China claim a larger political role in Syria or fund reconstruction?

11 April 2023

ATHENS — Saudi diplomats visited the Iranian capital on Saturday to discuss the reopening of both countries’ embassies, taking the latest material step towards restoring relations under a tripartite agreement announced by Riyadh, Tehran and Beijing in March.

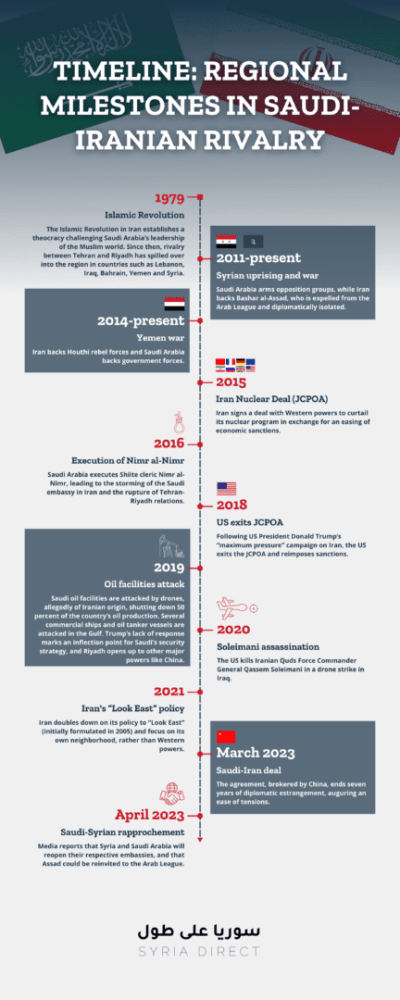

Saudi Arabia and Iran, moving to mend ties after seven years of diplomatic rupture and decades of a rivalry that has shaped geopolitics in the Middle East, have vowed to respect the principles of national sovereignty and noninterference under the agreement signed on March 10. The deal, brokered by China, arrives at a time when the United States (US) is increasingly shifting its focus away from the Middle East.

The broader geopolitical shift signaled by the deal has major implications for Syria, where antagonism between Tehran and Riyadh has played out over the past 12 years of uprising and war.

Rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran marks a “turning point” for the Middle East, according to Mona Yacoubian, Senior Adviser at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). “This is a watershed moment for a region that is [in] the midst of a generational shift into a new era defined by multipolarity, defined by powers in the region asserting their agency and not waiting on the US to solve their problems.”

After more than two decades defined by the US Global War on Terror, “the region is exhausted by hard conflict and is moving into this period where powers in the region seek to de-escalate tensions and are playing their interests first in an increasingly multipolar world,” Yacoubian added.

Amid perceptions of US disengagement from the region, China is expanding its presence. Beijing’s role mediating Saudi-Iranian talks positions China as a “new heavyweight diplomatic player in the region,” according to Alex Vatanka, Director of the Iran Program at the Middle East Institute (MEI). China’s economic ties with both countries gives it leverage but “it remains to be seen whether China can keep this agreement together,” Vatanka cautioned. “This is a major test for Chinese diplomacy.”

“Iran and Saudi Arabia have patched things up in the past and it fell apart—this could happen again this time,” he said.

The agreement itself “is a diplomatic win in the space of narratives,” according to Mollie Saltskog, Senior Analyst at the Soufan Group, a global intelligence and security consultancy. China is invested in “promoting an image of itself as a responsible power advancing dialogue, positioning itself as a peaceful and successful mediator in the Middle East, in contrast to the US.”

For Saudi Arabia in particular, however, the agreement does not mean less of a role for the US, said Henri Barkey, Senior Fellow for Middle East Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). “Saudi Arabia is dependent on the US: look at its military infrastructure, it is not the Chinese that are going to play the bigger role,” he said. “That may change in 20 or 30 years down the road, but I don’t think this deal is such a big deal in terms of Chinese-American competition.”

A normalization peak?

Following the Saudi-Iran agreement, Saudi leadership has reportedly agreed to reopen its embassy in Damascus, which was closed in 2012. Riyadh has also hinted at Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s readmission into the upcoming Arab League summit in May—12 years after Syria was suspended in response to the regime’s violent crackdown on protests in 2011.

Over more than a decade of conflict, the price of Assad remaining in power has included 135,253 people detained or forcibly disappeared, 15,000 killed under torture and at least 200,000 civilians killed, according to the Syrian Network of Human Rights.

Yet the readmission of Damascus into the diplomatic sphere has been underway for years: in 2018, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) reopened its embassy in Syria, followed by Oman in 2020 and Bahrain in 2021. Last year, Assad visited the UAE, and in 2023 he has so far been received by the UAE and Oman. In February, Jordan’s Foreign Minister visited Damascus for the first time since 2011.

Riyadh moving to re-engage with Damascus is part of “a broader conclusion by regional actors that Assad is entrenched in power and efforts of isolation have not yielded the kinds of benefits that they were looking for,” Yacoubian said. “Assad has won the civil war. That is something that the Arab countries recognize; from Egypt [and] Bahrain to [the] Emirates, Oman or Jordan, the writing was on the wall,” Vatanka echoed.

Saudi Arabia had originally penned a plan for “conditional normalization” with other regional powers, Firas Maksad, Senior Fellow at MEI, explained. However, other countries have simply “normalized without having Syria make good on any of these conditions, so Riyadh felt that it was left carrying the water on its own on this issue,” he added.

After initially backing armed Syrian opposition forces fighting Assad, Saudi leadership appears to acknowledge that “normalization seems to be the currency of the day,” Barkey said. Normalization with Assad may also give Riyadh “some leverage down the road on Syrian behavior in certain areas.”

One of Riyadh’s interests in reengaging with both Assad and Iran could be to stop the proliferation of Syrian-made captagon, a type of amphetamine, on Saudi streets. The Syrian regime is reportedly in control of this illicit drug market estimated to be worth billions of dollars, with cross-border smuggling into Jordan facilitated by Iran-linked groups. “There’s deepening concern about the captagon trade and the impact that that is having socially at home,” Yacoubian said. “The Saudis are looking to be able to wield greater influence on Assad to clamp down on that narcotic trade,” Yacoubian said.

Vatanka agreed there is “strong hope in Riyadh that one of the positive elements of engaging the Assad regime” would be Damascus giving up on this market, but he was skeptical Assad would oblige. The captagon trade “is the lifeline of the regime, Syria has become a sort of narco-state,” he said. “I’m very reluctant to believe that Assad would give that up as part of any opening with the Saudis.”

By restoring ties with Damascus, Riyadh could be “seeking to be a counterweight against Iran and Iranian influence” in Syria,” Yacoubian explained.

Rapprochement with Assad may be also explained by a “more transactional mindset” of Saudi and Gulf leadership, Vatanka said. “The Gulf countries that were fighting the Russians and the Iranians through proxies by backing the [Syrian] opposition have changed their game plan; they’ve decided that their future is about economic development and not these regional competitions.”

Iranian influence in Syria

Under their agreement, Saudi Arabia and Iran have each pledged not to interfere in the internal affairs of other states. Iran’s presence in Syria goes back decades, and throughout the conflict, the Iranian leadership has entrenched its military presence through militias and affiliated groups.

However, analysts agreed that this non-interference pledge was aimed primarily at Tehran’s backing of rebel Houthi forces in Yemen, rather than at Iran’s presence in Syria. “Saudi concerns with Yemen are far more immediate. Yemen is on its border and hostilities in Yemen have spilled to Saudi Arabia,” Yacoubian explained. Barkey agreed, saying the deal was aimed at “figuring out a way to minimize the damage” Houthis have inflicted on Saudi Arabia and its allies, referencing attacks on Saudi oil facilities in 2019.

Vatanka explained this deal provided a “give and take” situation for Saudi where “Iran would withdraw or stop being so supportive of the Houthis in Yemen, and in return, the Saudis will not be in the way of Iran remaining a powerful player in Syria.”

Neither Yacoubian or Vatanka foresaw a Saudi will or ability to push Iran out of Syria. Iran’s military presence in Syria has “strategic depth in the continuing shadow war with Israel, so there are factors there well beyond any issues or concerns that directly affect Saudi,” Yacoubian said.

In the long run, Vatanka saw the possibility that Iranians might conclude that they “should focus on their economic development at home. Iranians have very limited money, and if Syria becomes a burden for them economically where they can’t play a role in the reconstruction, Iran has to decide: Is it worth it?”

For now, Gulf states’ demand to Tehran could be not to make them into “frontline state[s] in [Iran’s] fight against Israel or the US; they have to move the fight from the Gulf region towards the Levant,” Vatanka explained.

Iranian forces regularly come under Israeli drone and artillery attacks in Syria, so Iran’s “revenge is more likely to be launched from Syrian or Iraqi soil, and far less likely to happen in the Persian Gulf or the Red Sea, because if that happens, Gulf states would become nervous,” he added.

“The Israelis are playing the game of bleeding Iran, not through one cut but 1,000 cuts, and that may work because the Iranians are constantly having to ask themselves: ‘We keep losing soldiers and we’re investing all this money, is it worth it?’” Vatanka said.

The impact of the Saudi-Iran deal on Israeli attacks on Syrian soil might not be straightforward. “I don’t think the Saudi-Iran rapprochement is directly affecting the Israeli calculus. The Israeli calculus is driven by Russia’s lack of attention or tacit willingness to allow Iran to play a bigger role on the ground in Syria in ways that were not the case before the Ukraine [war],” Yacoubian said, referring to recent Israeli strikes on airports in Damascus and Aleppo.

The Saudi-Iran deal may dash Israeli hopes of bringing Riyadh into the Abraham Accords—a US-mediated deal normalizing relations between Tel Aviv and some Arab countries. “Symbolically and geopolitically, this deal is not good news for Israel,” Vatanka said, although Saudi Arabia’s relationship with Israel “has far less to do with Iran and much more to do with their dialogue with Washington.”

China’s role

Beijing’s role in Saudi-Iran rapprochement shows that “China is acutely aware of geopolitics when dealing with the Middle East” and China’s interests can no longer be viewed through “an economic lens” alone, Saltskog said.

China’s main interest is to secure its energy supplies, she added. “Almost 50 percent of China’s oil imports come from the Middle East, so bringing stability to the Persian Gulf and decreasing tensions between rival powers like Saudi and Iran is in China’s interest.”

The recent deal could be a step forward on Beijing’s agenda to push for energy products to be traded in yuan. Most energy in the world is currently traded in US dollars. “If China is able to push forward deals where the primary currency is their currency, the renminbi, that provides a buffer towards US sanctions,” Saltskog said.

Last week, in a step consolidating Riyadh-Beijing ties, Saudi Arabia joined the Chinese-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), where Iran is an observer state, as a “dialogue partner.” Seventeen countries in the Middle East and North Africa, including Saudi Arabia, have joined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Beijing’s initiative to build infrastructure around the world to better connect China through land and sea routes.

Syria joined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2022. “Syria is important because it was part of the old silk road, so historically the narrative fits very well with China,” Saltskog said, adding that China has interest in gaining access to ports in Syria and Lebanon.

Saltskog warned about the risks of “jeopardizing sovereignty” by taking BRI loans. “We’ve seen with certain BRI projects where countries default on the loans and there’s critical infrastructure taken over on 90 year leases by the Communist Party,” she said.

If and when Damascus joining the BRI and China brokering the Saudi-Iran deal translates into investments in Syrian infrastructure remains to be seen. “If in the medium term there is investment under BRI, it might be more of an image-building mechanism rather than sound investments that they expect to get a return on,” Saltskog said.

Given Syria’s economic down spiral and high levels of corruption, Chinese investments in Syria are “a very long game; I don’t think that they are expecting a lot of return on investment,” she added.

Despite “significant” short-term obstacles, “I think the Chinese envision a role to play in Syria’s reconstruction,” Yacoubian said. “Chinese resources so far overshadow anything that the Russians or the Iranians could bring.”

On the security field, throughout the Syrian conflict, China’s priority in cooperating with Damascus has been the threat of violent extremism. “China is very worried about some of the extremists that are present in Syria that came from Turkey but are ethnically Uighurs,” explained Saltskog. “China has this idea that they pose a threat to China’s interest and Chinese homeland, from my analysis, the bigger threat may be to Chinese interest overseas along the BRI soft targets.”

Citing concerns over extremism, China has since 2014 cracked down on Uighurs, a Turkic Muslim minority group, and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang, northwestern China. Severe restrictions on movement, political expression and religious freedom, as well as the detention of more than one million Uighurs, have been described as crimes against humanity by the United Nations and as a genocide by the US.

China’s appetite to adopt a more political role in Syria remains an unknown factor. Throughout the war, China—like Russia—has used its veto power in the UN Security Council (UNSC) to back Assad, blocking condemnations or sanctions for the use of chemical weapons as well as resolutions for cross-border aid delivery.

China and Russia have been in “lockstep” in Syria, Saltskog said, referring to the two countries’ UNSC votes. However, while China has provided Damascus “some military aid and medical aid, they have not played the security role that Russia or Iran have played.”

For Beijing, in any decision on Syria their biggest consideration will be their relationship with Moscow. “If China would take a bigger role in trying to mediate the conflict in Syria that could actually step on Russia’s toes,” Saltskog said. “That’s something that China is very cognizant of balancing.”