Your brother is alive: The phone call that ended one Syrian family’s 11-year wait

In May, the Assad regime released 527 Syrian detainees under an amnesty decree that human rights defenders are calling arbitrary and insufficient.

30 May 2022

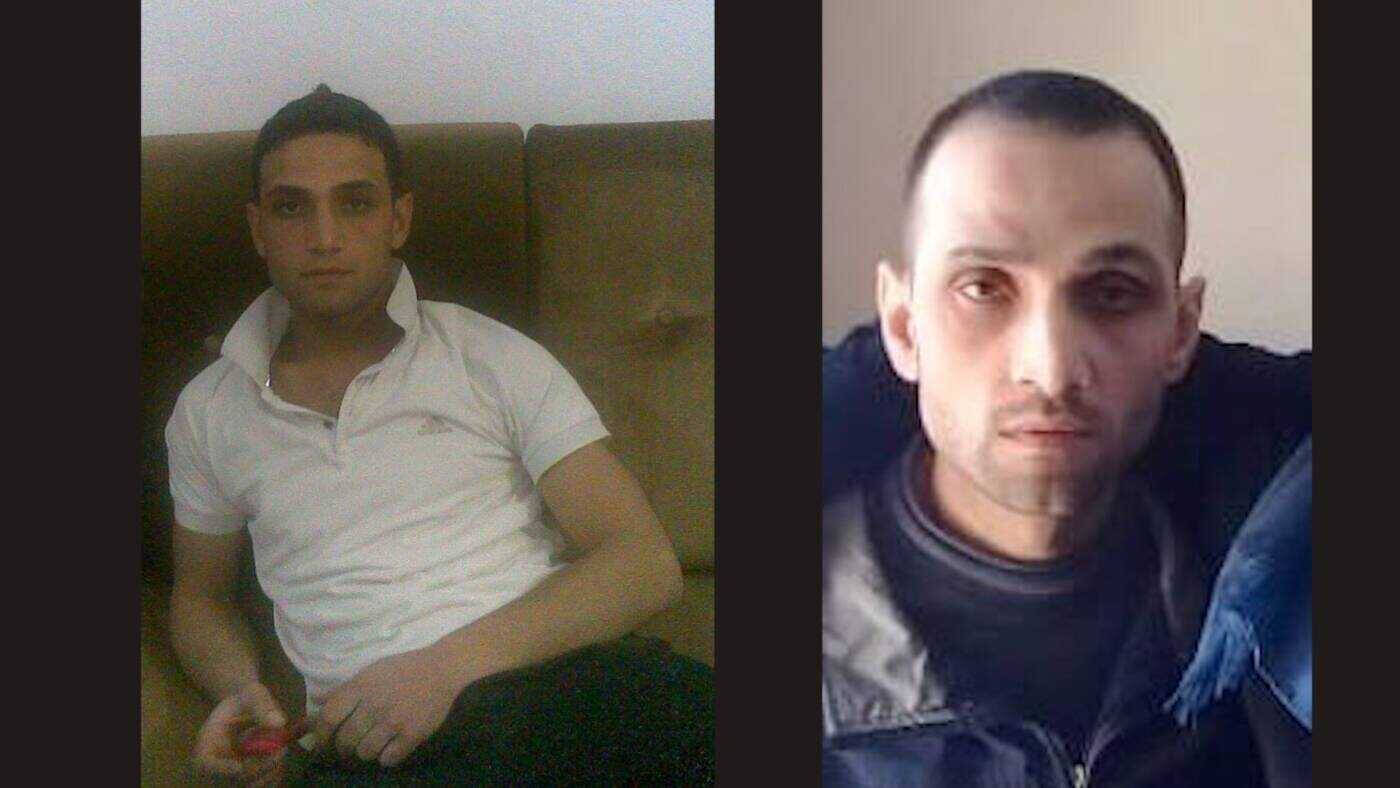

BEIRUT – A few weeks ago, a photo of a young man, his features pale and gaunt, was posted in a Syrian diaspora Facebook group. “This man just came out of prison and doesn’t know where to go. Whoever knows him—contact me,” the caption read. A few days later, Mahmoud Ayoub’s family received the phone call that thousands of families of Syria’s disappeared and detained have been anxiously waiting years for.

He was alive.

“When I heard the news, I can’t describe how I felt. I didn’t believe it,” Khalid, Mahmoud’s brother, told Syria Direct via a phone call from the Netherlands, where he lives in exile. “My brother has been detained for 11 years. We assumed he would never get out, that maybe he had died.”

Mahmoud is one of 527 detainees released so far under a general amnesty for terrorism charges issued by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad on April 30. Although the number of detainees released over the past month is higher than under previous amnesties, it remains a drop in the ocean of an estimated 132,000 detained and missing people in Syria, including 87,000 people forcibly disappeared by the Syrian regime, according to Syrian Network of Human Rights (SNHR) figures.

When the Syrian revolution began in 2011, Khalid’s family was among the first to join the coordination committees in Homs province. Mahmoud, 20 years old at the time, was completing his mandatory military service and at one point was sent to repress a protest in Deir e-Zor. The next time he received a similar order, he deserted. Soon after, he disappeared while crossing a regime checkpoint in Homs. After four years with no news, his family learned from a released detainee that Mahmoud was alive. He was in Saydnaya prison near Damascus, infamous for its systematic torture.

“He was accused of treason, terrorism, fleeing military service, collaborating and helping the protestors, ” said 33-year-old Khalid. “We lost all hope.”

Released in Damascus a few weeks ago, Mahmoud made his way to the opposition-held north, where he is recovering from poor health and has reconnected with his family through the phone, given they have all fled Syria.

“He’s not the same, the look in his eyes…he is physically and psychologically destroyed,” said Khalid. When he last saw his brother, Mahmoud was healthy and tall. Now, he is sick with tuberculosis, a shadow of himself.

“In 11 years, he didn’t step out of his cell, he didn’t see the sunlight,” Khalid said.

Mahmoud has shared horrific stories of his time in detention with his family. “He saw many die in front of him, people died from beatings, illnesses, hunger,” Khalid said. He had to inform Mahmoud that none of their family remained in Syria, and that two of their brothers were dead: one killed by the Syrian regime and the other by the Islamic State (IS).

More than 500 detainees released

Legislative Decree No. 7 of 2022 of April 30 covered detainees convicted of terrorist crimes—except those leading to the death of a person—under Counterterrorism Law No. 19 of 2012 and the General Penal Code.

Most of the 527 detainees released were civilians falsely charged with terrorism, Fadel Abdul Ghani, the director of SNHR said. While the vast majority of detainees in Syria were arrested in 2012 and 2013, “very few of those released were detained before 2015,” he said.

Among those released were 18 refugees who had returned to Syria in recent years. “Many of those who have returned to Syria have ended up being detained or disappeared, and the fact that a component of them have now been released only confirms this,” said Sara Kayyali, Syria researcher at Human Rights Watch (HRW).

“The writing on the wall couldn’t be clearer,” she added, criticizing governments that are “pushing for premature returns.” For the last year, the Danish government has been revoking residency permits of Syrian refugees on the grounds that Damascus and Damascus countryside are safe for return.

In Assad’s Syria, terrorism charges have long been used to silence political dissent. “Anyone who opposed Assad has been accused of terrorism,” Abdul Ghani said. Counter terrorism laws are a tool to “punish peaceful dissent, human rights activists, journalists—terrorism charges have been wielded by the Syrian government as a catch-all,” Kayyali said.

Because thousands of people have faced terrorism charges, hopes and expectations quickly spread following the April 30 amnesty. “Assad fooled many who thought this decree may include thousands,” Abdul Ghani said. But many people convicted of terrorism do not qualify for this amnesty, he explained, because the regime often charges detainees with multiple crimes, such as offenses against national security or the state. The amnesty also excluded crimes leading to death.

A turning point?

The latest amnesty marks a modest departure from the 18 previous ones issued by Assad since 2011. “In previous amnesties we had seen these laws being passed and then very little in terms of the number of people released,” said Kayyali, adding that under the April 30 amnesty “we’ve seen a larger number of released that align with people we had documented to have been detained or disappeared.” According to SNHR’s records, seven of those released were forcibly disappeared.

“It’s the first time that the pardon contains those convicted of terrorism, and releases some of the detainees from Saydnaya prison,” said Yasmin Mashaan, a founding member of the Caesar Families Association, which brings together Syrians who have identified their loved ones among the 50,000 photos—known as the “Caesar files”—smuggled out of Syria in 2013 that show thousands of killed detainees.

The UN Special Envoy for Syria, Geir Pedersen, after meeting with the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates, said the amnesty “has potential” and they were “looking forward to seeing how it develops.” Rights defenders are less enthusiastic.

“This arbitrary amnesty that is completely unilateral and is up to the good will of the Syrian government is deeply insufficient,” Kayyali said. “The UN should be playing a more proactive role in making sure of protecting detainees and making sure that people who have been arbitrarily detained are released.”

Mashaan called the decree an attempt by the Assad government to “whitewash its image in front of the international community and brand itself as cooperative.”

Although each detainee freed ends one family’s agony, the number released so far is “really a drop in the bucket,” Kayyali said.

Abdul Ghani stressed that the Assad government is still detaining people arbitrarily. In the month leading up to the amnesty, “Assad arrested 97 people, and this month as well, so on one hand he is releasing people but with the other hand he is adding new citizens to detention.” Abdul Ghani calculated that if Assad halted detentions, at a rate of 500 released per year it would take 260 years to release all detainees.

Besides the arithmetic behind the decree, for Mashaan, semantics are key. She is uncomfortable with the word “pardon.” “Pardon implies that you committed a crime and then he pardons you, but these detainees didn’t do anything wrong in the first place,” she said.

“The charges and the process by which these people have been detained were flawed,” Kayyali said. “You don’t need an amnesty for someone that has been arbitrarily detained, you should be releasing them without question.”

Syria’s Foreign Minister, Faisal Mekdad, characterized the amnesty this month as a “measure” to “achieve national reconciliations.”

Mashaan argued that an anti-torture law enacted in March, as well as the amnesty, should be read as efforts by the regime “to be seen in a better light.” She linked these steps to the pressure from an initiative by the Netherlands and Canada before the International Criminal Court to hold the Syrian government accountable under the Convention Against Torture.

A recent investigation by the Guardian exposing a 2013 massacre in the Tadamon neighborhood of Damascus may also have “sped up” the amnesty decree as an attempt to shift the conversation, Mashaan added. For Abdul Ghani, Assad’s recent visit to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) may have also played a role given that Assad is seeking the country’s economic support.

Dumped in the streets

As news of the amnesty spread early this month, hundreds of people gathered in squares in Syrian cities hoping their loved ones would be among those released. Authorities did not notify families or publish an official list, and in some cases simply brought detainees to central locations and left them in the street.

For Abdul Ghani, this approach to implementing the decree feels deliberate. “Assad keeps insulting Syrians, sending the message that he is dominating.” If so, it may have backfired. “He claims he doesn’t have thousands of people detained, but photos show thousands of families gathered waiting for their family members,” Abdul Ghani said.

This opacity has pushed some families to an extortion market in which prison officers take bribes in exchange for promises of getting their names included in the amnesty. “There needs to be public and transparent lists, a unified entity that is able to answer to family members inquiring [about their loved ones], the Syrian government needs to release the names of people who are detained,” Kayyali said.

Mashaan criticized the “inhuman” way the detainees have been released. “When you saw the families waiting on the streets, it was psychological torture,” she said. Even for some Caesar family members, the amnesty reopened old wounds and sparked uncertainty. “Some started doubting themselves,” said Mashan. Her brother Okaba disappeared in 2012 and three years later she found him among the Caesar photos. “I saw the photo of my brother and I know 100 percent that it is him. Still, I somehow found myself involuntarily checking the names of those released…what am I looking for?”

Khalid had been looking for his brother for 11 years, and many Syrians are still looking. When he celebrated his brother’s release on social media this month, Khalid was flooded with messages. “I received 7,000 message requests on Facebook asking me if my brother might know about their disappeared” loved ones, he said, his voice breaking.

“They were sending me photos of their brother, son, father, to see if my brother had seen them in prison.”

*Correction 6/6/2022: The original version of this report misstated the estimated number of people detained and forcibly disappeared in Syria as 132,000 people detained in addition to 87,000 people forcibly disappeared. This is incorrect. There are 132,000 people detained and disappeared in total, a number that includes 87,000 victims of enforced disappearance. Syria Direct regrets the error.