‘Suicide drones’ threaten Syrian farmers’ lives and livelihoods

Since late 2023, the Syrian regime has been waging a drone war in northwestern Syria. As civilians in areas near frontlines are targeted, the threat of attacks keeps farmers from their land, destroying livelihoods and threatening the area’s food security.

23 May 2024

IDLIB — Anwar al-Halabi, a 63-year-old farmer in the fertile Sahl al-Ghab region of Syria’s northwestern Hama countryside, no longer tends his land. He was injured in March by a suicide drone attack while in his fields near the frontline in al-Hamidiya village, and fears another strike could cost him his life.

Al-Halabi was riding his tractor, spraying pesticides on his wheat in the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)-controlled area of northwestern Syria when “the drone targeted me, leading to a broken knee, loss of part of my calf muscle and shrapnel being spread throughout different parts of my body,” he told Syria Direct. The blast also damaged his hearing.

Five days earlier, Muhammad Safi, a 58-year-old farmer who lives in the Sahl al-Ghab village of al-Daqmaq, suffered “severe injuries to my wrist and the ball of my foot when a suicide drone targeted me while I was riding my motorcycle to my land” on February 25, he said.

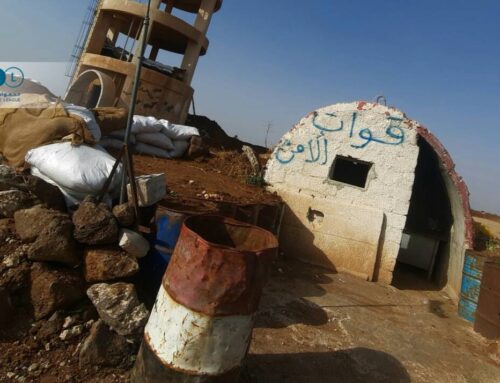

Since late 2023, the Syrian regime has been waging a drone war in northwestern Syria, particularly in areas close to the frontlines. Repeated drone attacks there in recent months have not only struck HTS and Syrian opposition military targets, but also civilians and farmers tending their land, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR).

The threat of drones has restricted farmers’ movement and limited their access to their land—from the Latakia countryside to the Sahl al-Ghab plain that straddles Hama and Idlib, all the way to the western Aleppo countryside. Farmers told Syria Direct their livelihoods have been destroyed.

From the start of 2024 to April 16, more than 60 suicide drone attacks killed 11 people and injured 32 others, among them four children and one woman, according to the Syrian Civil Defense (White Helmets).

“The regime uses locally manufactured [first-person view] FPV suicide drones, which are characterized by their small size and the operator’s ability to track and pursue the target,” Abu Amin, who monitors air traffic in the area’s skies to warn residents of possible strikes, told Syria Direct. Abu Amin works within the al-Fatah al-Mubin operations room, a military formation that includes HTS, but is not part of any faction.

Abu Amin monitors air traffic above Syria’s northwestern Idlib province, 10/5/2024 (Abdul Razzaq al-Shami/Syria Direct)

“This weapon is being developed at the Scientific Research Center in Hama under the supervision of Russian and Iranian experts,” Abu Amin said. He noted these aircraft can fly at an elevation of less than 30 meters for a distance of 10 kilometers, carrying a payload of 1.5 kilograms of explosives.

The Syrian regime’s 25th Division, Republican Guard and 5th Corps-Storming are responsible for using the suicide drones, “launched from the most forward position of the lines of contact to reach the greatest depth,” he added.

The monitor described the drones as “dangerous weapons” because “the error could be zero, compared with conventional weapons.” Safi, the farmer who was injured in February, knows this from personal experience. “I ran from it for two kilometers, but it kept chasing me until it hit me,” he said.

Livelihoods under threat

Farming is the main source of income for residents of the fertile Sahl al-Ghab plain, where 30 percent work in the agricultural sector, according to Tamam al-Hamoud, the Director-General of the HTS-backed Syrian Salvation Government’s Directorate of Agriculture.

Continued drone attacks could lead farmers to stop cultivating their land near the line of contact. This would harm the economic situation and food security in northwestern Syria as a whole, as Sahl al-Ghab and the western Aleppo countryside are “two of the most fertile and productive areas for wheat,” al-Hamoud explained.

Around 15,000 hectares of wheat in Sahl al-Ghab could be lost as a result of the drone attacks, according to figures provided by the SSG’s Directorate of Agriculture. The annual production of this area is around 37,000 tons. Another 5,000 hectares of beans, potatoes and tree crops face a similar fate.

Farmland in Syria’s northwestern Sahl al-Ghab lies below mountains where Syrian regime forces are stationed, 10/5/2024 (Abdul Razzaq al-Shami/Syria Direct)

Al-Hamoud worries that northwestern Syria faces a “real problem related to basic food for the population” if drone attacks persist and prevent farmers from harvesting the strategic wheat crop. “The targeting coincides with the [World] Food Program [WFP] very significantly reducing its food assistance to northwestern Syria,” he said.

At the start of 2024, the United Nations’ WFP suspended all in-kind food assistance across Syria, while continuing to provide limited emergency assistance.

Read more: Syrians lose WFP lifeline as US slashes funding

The harvest, which usually starts in June, is fast approaching. Safi does not plan to risk going to his land to harvest his wheat, even though he paid $500 to plant the entire area of his 10 dunums.

Reluctance to harvest their land leaves farmers like Safi facing enormous economic challenges. “Losing the crop will affect my livelihood, but losing the season is better for me than to be injured a second time,” he said.

“I will rely on my five head of sheep, the only ones I have, to make a living until next season,” the farmer added.

Anwar al-Halabi’s loss is greater. On top of his physical injuries, his tractor was also damaged in the attack. He estimated it will cost around $1,500 to repair it. Not being able to harvest his 20 dunums of wheat also means losing the $1,000 he invested in his crop.

Farmer Anwar al-Halabi, 63, sits in front of his tractor, which was damaged by a suicide drone attack in al-Hamidiya, a village in the Sahl al-Ghab region of northwestern Syria, 7/4/2024 (Abdul Razzaq al-Shami/Syria Direct)

“If the drone attacks continue, I won’t be able to harvest the wheat,” al-Halabi said. He supports his family of five with the fruit of his land.

While northwestern Syria’s farmers anxiously bide their time, waiting for the harvest and fearing their crops could be burnt as regime forces and opposition forces exchange fire, regime-affiliated media lauds the novel weapons.

On April 24, an article in the pro-Damascus newspaper al-Watan praised how “the army’s targeting of terrorists with drones and heavy artillery since the start of the week has created a state of terror in their ranks and limited their appearance in the Sahl al-Ghab sector.”

‘Taking your life into your own hands’

In years past, Sahl al-Ghab’s fields would be crowded with agricultural machinery and farmworkers during the summer months. As summer approaches this year, machinery is scarcely seen, farmers told Syria Direct. Going to the fields, given the presence of the drones, means “taking your life into your own hands,” al-Halabi said. “Need pushes some to risk it, but the cost could be a life.”

Some farmers have tried to go to their land at night, because suicide drones are not launched at that time. Al-Halabi downplayed the usefulness of that option, since “it is difficult to get workers at night, and you can’t see.”

When it comes to the drones, the only solution is “to take cover from them,” al-Hamoud of the SSG said. “Once they spot the target, they will undoubtedly hit it.”

However, hiding from suicide drones in open areas and main roads is “extremely difficult,” Fatima al-Hassan, a 50-year-old resident of Farika, a village overlooking Sahl al-Ghab, said. Her husband was injured by a drone attack while driving a water tanker truck on a public road in the area in February.

The blast damaged the water tanker, “our only livelihood,” al-Hassan told Syria Direct. After the incident, her family got by with financial support from other villagers, as well as taking out loans.

While al-Hassan’s husband survived, Hosna al-Bakro lost her oldest son after he was targeted by “a suicide drone with other workers” while returning from work near Taqad, a town in the western Aleppo countryside, on April 23.

“My son was killed immediately, and the other workers were injured,” the 76-year-old mother said, trying to hide her tears in front of the nine children her son left behind. “He was the pillar of our family, our only breadwinner after God,” she added. “He went and left these mouths to feed, the oldest of whom is no more than 12 years old.”

Jihad al-Amaqi, al-Bakro’s 41-year-old son, worked as a day laborer in agriculture and construction. He earned between 150 and 200 Turkish pounds a day ($4.65-$6.20), his mother said. “Despite the small amount, he supported us,” she added. “We now have no breadwinner, and I don’t know how to feed my grandchildren.”

Al-Bakro’s family is one of 500 families living in Taqad. The town sits just three kilometers from the regime-controlled village of Basartoun in the western Aleppo countryside, leaving it vulnerable to targeting by suicide drones, Ahmad Hamdo Barakat, the mukhtar—administrative chief—of Taqad, told Syria Direct.

“We have no other option. We are forced to remain in our town, because life in the camps is difficult and we have no ability to secure rent for housing in far-off cities,” al-Bakro said.

While suicide drones threaten the lives of civilians near the frontlines and bleed the local farming economy, Idlib’s Directorate of Agriculture has no means to compensate those who are impacted or lose their harvest, al-Hamoud said.

“We have some provisions set aside at home that will last us through the end of summer,” farmer al-Halabi said. “After they run out, I don’t know what I’ll do.”

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.