Nowhere to run: Syrian refugees face Damascus’ security apparatus in the EU

Hundreds of thousands of Syrians sought refuge from the Syrian government in the EU; however, Damascus' security services are determined to follow them.

23 October 2019

Syrians raising the Syrian revolutionary flag in a Berlin square, 21/03/2017 (The Syrian Revolution Coordination Committee of Berlin)

To listen to the investigation: click here

BERLIN—Though the European Union (EU), and Germany in particular, have become a safe haven for Syrian refugees, some refugees—mainly political and humanitarian activists—continue to be haunted by the long reach of the Syrian government’s security apparatus, especially as talk of regime change becomes a thing of the past.

The Syrian government “seems to be stable now,” the German journalist, Harald Etzbach, told Syria Direct. As a result, there has been a “decrease in the number of demonstrations against the Syrian regime, and involvement of refugees in educational and cultural projects far removed from political activities,” he said. Damascus’ consolidation of power just adds to how “exhausted they’ve become,” he added.

If the stability of the Syrian government alone scares refugees, then “the regime’s policy of spying on old immigrants and recent refugees with the help of other refugees, [similarly] increases their fears,” a former Syrian diplomat living in Germany told Syria Direct anonymously.

The former diplomat, who worked in several Syrian diplomatic missions during his career, added that: “the regime relies on immigrants and refugees to track their peers and to ascertain who is against it and who is with it. They do what the embassy cannot do directly with regards to refugees.”

“Certain actions that embassy employees were requested to facilitate for [citizens abroad] mention that they will visit a security branch in Syria, which points to the fact that they are working for the regime or in some cases, are forced to give information under pressure and threats,” the diplomat said.

The fear of informants lurking among asylum-seekers is widely shared among Syrian refugees, something which caused many sources in this investigation to avoid direct interviews, preferring to provide information and documents electronically instead.

“It’s not outside of the realm of possibility for the regime to send people under different covers, journalists or people working in civil society organizations, research centers and otherwise,” Abdul Jalil al-Hourani, a Syrian refugee living in Berlin, told Syria Direct.

Old spying techniques, new refugees

On March 17, 1981, Syrian security services assassinated Benan Tantawi, the wife of the former Inspector-General of the Syrian Muslim brotherhood in Syria, Issam al-Attar, in the German city of Aachen. A gunman broke into their home to assassinate al-Attar, but he was not in the house. Instead, the gunman killed Tantawi, shooting her five times.

Prior to Tantawi’s murder, the former prime minister and co-founder of the Arab Socialist Baath Party, Salah al-Bitar, was assassinated in 1980 in France.

Despite the identity of the assassin remaining unknown, Hafez al-Assad’s government was widely accused of carrying out the assassination, especially as it came after a dispute between al-Bitar and Assad.

These events and others following Syria’s 2011 revolution, in addition to documents obtained by Syria Direct over the course of its investigation, paint a picture of a regime willing to go to any lengths to crush dissent at home and abroad, and of a Syrian diaspora facing a real and present danger.

The murder of Muhammad Jona, a Syrian pharmacist, in Hamburg, Germany in January, harkened back to the assassination of Tantawi, frightening many Syrian refugees.

German media outlets reported that Jona could have been killed due to his activism against the Syrian government, something that only served to further alarm Syrians living in Germany. German police had not confirmed the media’s speculation at the time of publication.

Damascus carries out its agenda in the EU countries through civil society organizations which have direct ties with Syria’s security apparatus or with Syrian embassies, according to a member of the European Institute for Political Initiatives and Strategic Analysis (EIPISA), Dr. Bassem Hatahet, a Belgian humanitarian activist who is of Syrian descent.

Among the organizations that are affiliated with Damascus is the “National Syrian Student Union,” according to Hatahet. “They used to hold their meetings in the Syrian embassies in Europe, before the severing of diplomatic ties [with Damascus],” he said. “[They] were also responsible for organizing marches in support of the regime after every opposition demonstration in Europe.”

In addition, businesspeople of Syrian origin played a prominent role in supporting the Syrian government and its agenda in the EU. A number of them were members of the “Syrian Expatriates Association,” a group which “made huge efforts to coordinate meetings between Syrian representatives and their [EU] counterparts and in chambers of commerce,” according to Hatahet.

“With the outbreak of the revolution in March 2011, they unified under Assad and helped fund marches in support of him, as well as penetrated protests against him.”

However, according to the director of the Munich-based European-Arab Human Rights Organization, Kazem Hindawi, “the regime has not established any new security organizations in Europe, because it never left Europe.”

“It surveils the movements of refugees and practices its security and investigative work through different methods and forms to pursue Syrians,” Hindawi told Syria Direct. He confirmed that business people supported the security agenda in the past and were even bolder than “the Shabiha [pro-regime thugs] refugees who were concerned with their asylum claim and residency status.”

Damascus also relies upon far-right extremist parties to tarnish the reputation of Syrian refugees and provoke “hate speech” against them, according to the director of the Syrian Commission for Justice and Accountability, Hassan al-Aswad.

“It’s easy for the Syrian regime to support extremist or right-wing organizations and parties—which is something that it does—to sway public opinion against refugees,” al-Aswad told Syria Direct. This is in addition to the government’s ability “to send well-trained members of its [security] apparatuses to perform acts of sabotage that are attributed to refugees.”

In one example of right-wing incitement against refugees, pro-Damascus Syrian refugee Kevork Almassian described Syrian refugees as “weapons of mass destruction against Europe.”

Almassian, who is of Armenian descent and reached Germany in 2015, has participated in several conferences hosted by the anti-refugee Alternative for Germany (AfD) party and has made no secret of his support for Bashar al-Assad, according to a report by Deutsche Welle TV station in March.

Damascus’ eyes in Berlin

In Berlin, the dissident colonel sensed that the Syrian government was keeping a watchful eye on him, following him constantly. Yet in contrast to Syrian agents in cities beyond the German capital, the colonel, speaking on the condition of anonymity, believes that “Syrian agents in Berlin are more organized,” adding that they are “distributed throughout streets and neighborhoods, moving back and forth from Damascus.”

While the possibility of news about his whereabouts and activities reaching Damascus undoubtedly poses a threat to the colonel, other activists face more tangible risks, as is the case with the Syrian opposition activist, Maysoun Berkdar.

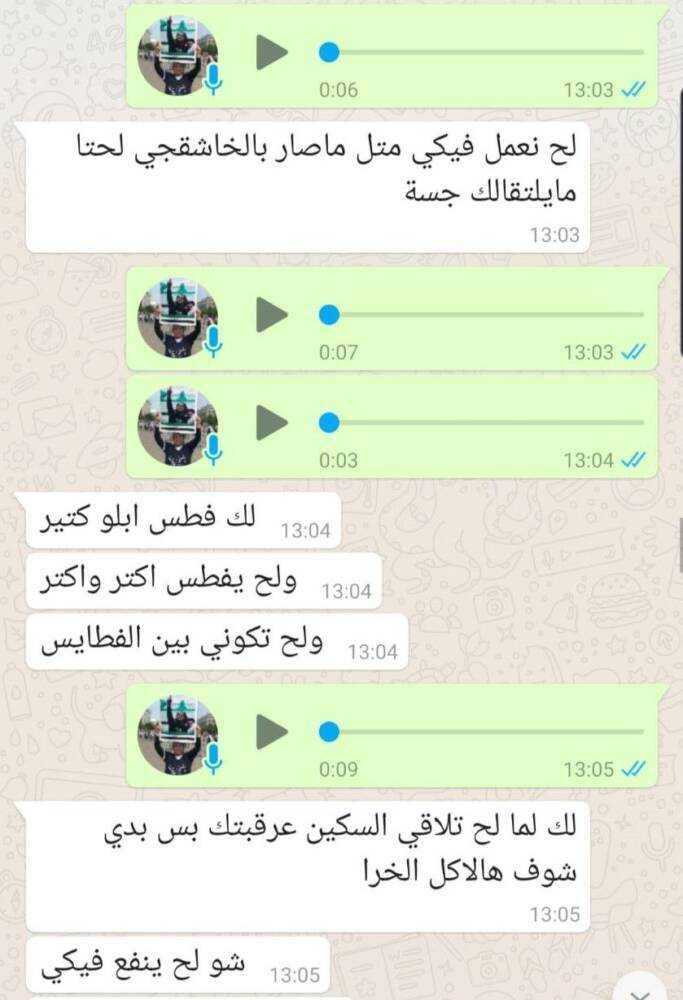

Berkdar told Syria Direct that she has received a number of death threats and provided evidence of voice recordings and screenshots of conversations with explicit threats from people inside Germany and Syria.

Some of the threats, seen by Syria Direct, read, “We will do to you what they did to [Jamal] Khashoggi. When the knife meets your neck, I want to see how well it works on you.”

Berkdar received similar threats from Omar Rahmoun, a member of the so-called “National Reconciliation Committee,” which is affiliated with the government in Damascus.

When she threatened to send him to court in Germany, he responded, “the German intelligence services that you are threatening me with are actually coordinating with us in Syria.”

Screenshots of threats that Maysoun Berkdar received through Whatsapp and Facebook (Maysoun Berkdar)

In one of the audio recordings, someone with a Lebanese accent, noting that he was from the city of Tyre, vowed to eliminate the Syrian revolution, declaring that Lebanon “is for one person, Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah [the Secretary-General of Hezbollah], and Syria is for the crown head, Bashar al-Assad.”

Berkdar told Syria Direct that she “filed a formal complaint with the German police and attached the necessary evidence,” without adding any further details.

Lara Qabani, a Syrian journalist and activist, also received a message on Facebook, just hours after she arrived in Berlin, from someone claiming to work at Orient News, a Syrian opposition channel headquartered in Dubai. The person claimed that he wanted to meet Qabani to conduct a television interview with her.

Qabani, an anti-government activist, told Syria Direct that she felt he was luring her in an attempt to gather more information about her. She then contacted a journalist working at Orient News in Berlin who denied that this person worked at the office. This prompted her to “report the case to the German police, who in turn, identified the person and placed him under surveillance,” she noted.

In another incident, Abdul Jalil al-Hourani, who spoke under a pseudonym for security reasons, had several threats directed against him in Berlin. He recalled an incident when someone “tried to enter his house by force when he was absent, but failed.”

Cross-border threats

Commenting on the dangers Syrian refugees in Germany face from the Syrian government, human rights lawyer, Anwar al-Bunni, told Syria Direct that “even if the threats come from criminals associated with the Syrian regime, they are too cowardly to translate their threats into actions in Europe, because that would risk being further complicit [in criminal actions].”

But even if the EU’s security policies have prevented any operations against Syrian refugees on European territory, refugees face threats in different forms, such as the targeting of family members who remain in Syria.

“The regime called my family in Daraa for questioning,” al-Hourani, who is from Daraa province in southern Syria, said. “During the interrogation, they asked about my youngest son, who was born in Germany and whose information was not documented by the Syrian embassy or any other Syrian governmental institution.”

“If my relatives in Syria don’t even know about the precise details about my youngest son, who other than regime informants can gather information about refugees and pass them onto branches of the regime?”

Ali Hassan’s family was similarly targeted. After the Syrian government took control of eastern Ghouta in April 2018, his family was regularly summoned by the security services in Damascus and were constantly pressured to “find out my current whereabouts and my past and present activities,” he told Syria Direct.

Now 40 years old, al-Hassan lives in a small village in the French countryside. A human rights activist, he was forced to flee from Eastern Ghouta to northern Syria, and then to France. On his journey, he revealed he took with him “the secrets of Eastern Ghouta, including sensitive issues such as the use of chemical weapons” by government forces against Syrian civilians.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in March 2011, al-Hassan has helped document violations committed by military forces in Damascus and its countryside. His latest work “documented the crimes of the regime during the last military campaign and contributed to several human rights reports on internationally prohibited weapons.”

Working on the latest report left him feeling as if “the threats accompanied me to my new place of residence, [however] the threats are more tangible for his parents who preferred to stay in Syria.”

Aside from fearing for his family, he feels guilty that he placed his family in a situation where interrogations could turn into abuses. “[I] am not safe and am fearful of the way that regime security services will deal with me and my family, both in and outside of Syria.”

As the former Syrian diplomat revealed to Syria Direct, “the regime uses a ‘carrot and stick’ approach in its threat to refugees.” While the ‘carrot’ comes in the form of “declarations of amnesties and pardons, encouraging people to return to their country,” the ‘stick’ is the “enactment of laws that harm the interests of refugees in Syria.”

One such law is “the property confiscation law in Syria,” under which the government has seized the cash and assets of Syrians opposed to the government, according to the former diplomat.

Visiting Damascus, at a cost

In Germany, government officials and media outlets have begun to take issue with refugees returning to visit Syria. While the German government has not accused refugees visiting Damascus of working for the Syrian government, the German Interior Minister, Horst Seehofer, submitted a proposal last August to withdraw asylum or deport Syrian refugees who returned to their country.

In the German tabloid, Bild am Sonntag, Seehofer was quoted saying that “if somebody, a Syrian refugee, regularly takes holidays in Syria, he cannot honestly claim to be persecuted in Syria and we would have to strip him of his refugee status.”

In addition, in the eyes of Syrian refugees, Syrians visiting Damascus from Germany could constitute a threat to those fleeing persecution by Syrian security services.

According to the dissident colonel, “every person who visits Damascus and then returns to Europe serves as the regime’s watchful eye in Germany, whether recruited into this mission or forced to comply with it.”

He pointed out that, “all who enter Damascus present information about their refugee neighbors in Germany.” They are “coerced into giving up the information whether they want to or not.”

Prosecuting Damascus’ security agents

Occasionally, Syrian refugees and Syrian opposition media outlets will share photographs or information about individuals affiliated with Syrian security services or loyal to the Syrian government.

In May, Zaman al-Wasl website published information about a former intelligence officer in Syria who arrived in Germany in 1998 and now lives in North Rhine-Westphalia state.

In one of the photos published by Zaman al-Wasl, the rear windshield of one of Yasser al-Tanji’s cars appears to be covered with a portrait of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his brother Maher, commander of the Fourth Division.

A portrait of Bashar and Maher al-Assad covers the rear windshield of a car belonging to the Syrian-German Yasser al-Tanji in North Rhine in western Germany (Zaman Al Wasl)

According to the president of the Syrian Center for Legal Studies and Research, Anwar al-Bunni, though the Syrian government has agents in Europe who “have sent to reports to the regime,” they cannot be prosecuted unless the evidence proves that “their reports have led to the arrest or crimes committed against Syrians.”

“If there is evidence, we can prosecute them in the EU,” al-Bunni said.

There have been cases of people being “exposed to threats from Shabiha,” al-Bunni said, and that the subsequent legal complaints have been dealt with “seriously” by German authorities. In some cases, authorities have followed up on these complaints by “arresting those that had threatened others or acted aggressively towards them.”

However, the actions of the German authorities appear to have been more pronounced in the prosecution of war crimes. In February, German authorities arrested two former Syrian intelligence officers and a third in France for war crimes in Syria.

Al-Bunni is a part of a group of anti-Assad activists who have contributed to the investigation of “Syrian war criminals” currently present in the EU. The group also helped in the issuance of German-French arrest warrants for a number of high ranking Syrian government officials, including the November 2018 memo issued against three Syrian intelligence officers: Chief of Air Force Intelligence Jamil al-Hassan, Director of National Security Ali Mamlouk, and Chief of Air Intelligence Investigation Branch Abdul Salam Mahmoud.

Germany employs “unjustified” policies towards refugees

Germany tops the list of European host countries for Syrian refugees. By the end of 2018, there were about 526,000 refugees in Germany, according to the Federal Statistical Office of Germany.

The large number of refugees has allowed “former government soldiers from Damascus and its intelligence agencies to infiltrate the refugee [population], prompting a number of European countries, including Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, to reopen their refugee files and scrutinize them again,” according to Hatahet.

For his part, Hindawi criticized the German judiciary for “neglecting to prosecute criminals and collaborators with Damascus,” a failure which was “one of the reasons the Shabiha were able to infiltrate the refugee [population]” arriving in Europe.

However, the Syrian-German lawyer Nahla Othman, who specializes in asylum and refugee affairs, attributed the German government inaction towards those accused of spying for the regime to a “lack of sufficient evidence.”

Othman was assigned several cases by Syrian opposition members in Berlin. The case owners claim to have been threatened by people working for Damascus. “One of the cases revealed evidence and information, and I was able to proceed with the legal procedures to convict the defendant,” she told Syria Direct.

Al-Aswad agreed with Othman on the issue of “insufficient evidence” and added that other obstacles impede the work of the German judiciary in prosecuting criminals. Particularly, “the limited capacity of the German War Crimes Unit, which is the executive body responsible for investigating alleged crimes. Furthermore, the evidence [in many cases] does not conform to the standards of the European judicial system,” he said.

Syria Direct has tried to obtain an official comment from the Federal Prosecutor’s Press Office at the German Federal Court of Justice but had not received a response at the time of publication.

While stressing the importance of the role Syrian organizations play in prosecuting war crimes, al-Aswad believes that “Syrian organizations still need more training to reach the required standard. There is no Syrian organization that can build a comprehensive criminal file according to the standards of the International Criminal Court or the standards of any European national criminal court so far.”

In addition to limited judicial prosecution, the German government has adopted a number of restrictive policies towards refugees who hold temporary protection cards. Such measures are viewed as “strict, unjustified and constituting a threat to Syrian refugees” according to several sources.

Said al-Homsi, a 35-year-old Syrian refugee living in Cologne, said that “the German government is responsible for some incidents of spying on Syrian refugees in Germany.”

“Since most Syrians who arrived in Germany don’t hold official Syrian travel documents, the German government granted them temporary residence permits for a year and requested they check in with the Syrian Embassy in Berlin for Syrian travel documents.”

For opponents of the Damascus government, the request is a “forced return to war” according to Omar al-Ahmad, a 50-year-old refugee living in Stuttgart, Germany.

“Since I left my city in the eastern countryside of Homs after the regime took control and until I arrived in Europe via Turkey, the regime has not had any information regarding my whereabouts,” al-Ahmad said.

“Should I go to them myself and update them with my information and place of residence in Germany?”

This investigation was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Will Christou, Rohan Advani and Nada Atieh.

This investigation was supported by OPEN Media Hub, with funds provided by the European Union