Strict Turkish conditions to renew tourist residency leave Syrians at a loss

In April, Turkey tightened conditions for renewing tourist residencies, requiring Syrians to show bank deposits of 1.5 times the minimum wage per family member or obtain work residency instead. The requirements are beyond the reach of many.

20 June 2024

MERSIN — After spending two years in Turkey on a student residency permit, Wissam (a pseudonym) changed his status to tourist residency in 2021. It was “the only available option” after he had to abandon his studies at a university in Istanbul.

Over the following years, Wissam, a man in his 30s originally from Hama city, usually had no trouble renewing his one-year tourist residency. But the last time he tried to renew it, around a month ago, he received a six-month residency instead. He also had to sign “a pledge to change it to a work residency before it ended,” or deposit around $10,000 in his bank account to be able to renew the permit for a full year, he told Syria Direct.

In late April, Turkey’s Directorate of Migration Management set new conditions for renewing tourist residencies, without issuing a formal decision. These conditions included renewing permits for only six months. Those who wish to stay in Turkey with this status for longer than a year are required to sign a “document of responsibility” committing to change it to work residency or, alternatively, to show they have an income of at least 150 percent of Turkey’s minimum wage of 17,000 Turkish pounds (TRY) ($580) a month for each family member, to be deposited in their bank account.

Wissam, who works at a Syrian humanitarian organization in Turkey, worries about the future of Syrians, like him, with this type of residency. “The conditions to renew are still unclear,” he said, leading to “a constant state of alert, fear and uncertainty about how to deal with the new decision, especially as relates to depositing money in the bank.”

Also in April, Turkish authorities activated the National Electronic Reporting System (UETS), an mobile application managed by the Turkish postal service (PTT) where residents receive official notifications regarding the status of their renewal applications.

There are 591,960 people in Turkey under tourist residencies as of June 6, according to statistics from the country’s Presidency of Migration Management. Syrians are the fourth-largest group with tourist residency—with 56,611 people—after Iraq, Turkmenistan and Russia.

Obstacles

Wissam is looking for a way to obtain a work permit and convert his tourist residency to work residency. “Achieving this is difficult because of the conditions required to grant a work permit,” he said. Turkey requires “business owners to employ five Turks for every foreign worker,” a condition that is difficult to meet, especially in professions where Syrian labor is prevalent, and which is not met at Wissam’s workplace.

“Most non-Turkish companies do not have the number of Turkish employees required by the authorities,” Istanbul-based legal consultant Majd al-Tabbaa said. This is what drove many to previously obtain tourist residencies instead, “and they are now finding it difficult to obtain work residencies in their place.”

Most clients who come into al-Tabbaa’s office in Istanbul, who received a tourist residency extension after the new conditions went into effect—that is, a six-month extension—“are trying to find work at companies that allow them to obtain a work permit, in order to get work residency later,” he added.

The process of registering employees also requires them to contribute to Turkey’s Social Security Institution (SGK), which deducts 35 percent of an employee’s monthly salary. This amount is either paid by the employer or split between the employer and employee. Most often, “the employer refuses to sign a contract with the employee and register it with the notary,” Wissam said.

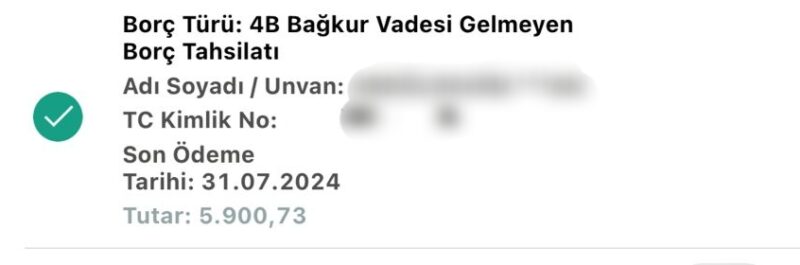

An SGK tax notice to an employee making the minimum wage of TRY 17,000 per month (Syria Direct)

In a questionnaire Syria Direct distributed to 25 Syrian refugees with tourist residency in Istanbul, Gaziantep, Mersin and Izmir provinces, 70.8 percent said they have faced several difficulties in renewing their permits. These included rejected applications, a lack of clarity regarding the required conditions and residency being renewed only for a short period. Respondents said they were not able to obtain a work permit allowing them to obtain work residency.

Others said they could not secure the amount of money required by Turkish authorities to demonstrate financial stability for themselves and their family members, as in the case of Ezzeddin (a pseudonym), a man in his 50s from Syria’s Reef Dimashq province.

Ezzeddin lives with his wife, mother and two sons in Mersin, a city in southern Turkey. He holds a Kimlik—a temporary protection card granted to refugees—but the rest of his family members hold tourist residency, he told Syria Direct.

His family has an appointment to renew their residency in September, but they are not able to secure the required bank balance—a condition for a one-year renewal—nor can they change to work residency.

“I don’t know what to do. There’s no possibility of traveling to another country, because there are no countries taking Syrians, and they can’t get Kimliks,” Izzeddin said. Turkey stopped granting Kimliks to Syrians in February 2022.

Other challenges Syrians face in renewing their residencies include difficulty renewing Syrian passports and not being able to obtain personal status documents from regime institutions. This is especially difficult for those who are defected from or wanted by the Syrian regime, 66.7 percent of those who responded to Syria Direct’s survey said.

Syrians have faced other administrative obstacles for years, including the challenge of establishing and registering residential addresses with Turkey’s Directorate of Migration. When Syrians have to vacate their homes, they often have trouble establishing a new address. They are prohibited from registering in some areas if the number of foreign residents is greater than 25 percent, and sometimes depending on the mood of officials, as one employee at Dalil Tourism Investments, a company that helps Syrians complete residency procedures, told Syria Direct.

The employee recalled one Syrian family from the Homs countryside—a mother and three daughters—who had to leave Turkey after they moved to a new home in Istanbul. The mother could not register with the Population Department at their new address, while her daughters could because they were university students, he said.

“The family had been staying in a house in the Fatih area for three years, but the municipality asked them to vacate the building because it is old and not earthquake-resistant,” he said. After searching, the family found a house in the area of Akşemsettin, but the mother could not register there due to the cap on foreign residents. “The family decided to return to where they previously lived in Kuwait,” he added.

Why tighten requirements?

In early May 2022, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced an eight-stage plan for the “voluntary” return of a million Syrian refugees to reduce the number of Syrians in its territory.

The following year, 2023, saw 103,045 Syrians return “voluntarily to their country,” as Turkish Interior Minister Ali Yerlikaya announced this month. That brought the total number of Syrians who returned, between 2016 to 2024, to 658,463.

Clamping down on tourist residency holders is an extension of Ankara’s policies towards Syrians aiming to “push them to leave the country,” lawyer Ghazwan Koronfol told Syria Direct. The requirement to deposit a monthly income of 150 percent the minimum wage “is a longstanding clause for tourist residency, but it is currently being enforced with the aim of organizing tourist residencies and reducing the number of [such] residents in Turkey,” he added.

Obtaining a full year tourist residency requires a person to deposit TRY 25,500 for every member of the family per month, or a total of TRY 306,000 a year ($9,925), an amount that is beyond the ability of most Syrians with this status. The alternative is to “obtain a work permit allowing the person to obtain a work residency, and a family residency for the family, which expires when the work permit expires if it is not renewed,” Koronfol said.

The problem is that “the number of work permits is small—less than 60,000 since 2012—compared to the 1 million Syrians working in Turkey,” Koronfol, who works as a legal consultant in Mersin, said. This underscores “the difficulty of obtaining or renewing a work permit, due to obstacles or administrative red tape, with no logical explanation,” he added.

In addition to the limited options available to Syrians, they also run up against the “sudden application of decisions before they are announced, or decisions may be applied to them without being announced,” the Dalil Company employee said. The latest of these is “the pledge document obliging a person to convert their residency to work residency or deposit a sum of money in the bank,” he added.

Commenting on that, Inas al-Najjar, the communications director at the Syrian-Turkish Joint Committee, noted “tourist residency conditions remain the same,” pointing out that “activating them aims at finding out the number of residents and tourists in Turkey, and distinguishing between them, especially with the increasing number of people of all nationalities obtaining tourist residencies to settle down,” she told Syria Direct.

Human rights activist Taha al-Ghazi agreed, saying the Presidency of Migration Management aims, through the newly applied tourist residency conditions, to “organize the presence of foreigners in Turkey.” However, this effort “was essentially putting up obstacles,” he said.

“We’ve noticed employees are temperamental about renewing or rejecting residency applications,” al-Ghazi added. “There is no fixed legal system or authority protecting Syrian refugees or other foreigners.”

The interior ministry’s measures “are in the framework of countering illegal immigration, but when applied their course has been diverted in directions that include legal violations,” al-Ghazi said. “Some administrative employees or police officers started to see every foreigner as an illegal immigrant, creating an environment of violations against legal residents in Turkey—Syrian refugees and [other] foreigners alike.”

At a meeting organized by Istanbul province for international civil society organizations this month, attended by Governor Davut Gül as well as the head of the Directorate of Migration and the head of the Istanbul Population Department, representatives of the Syrian civil society presented two proposals related to the new conditions for tourist residency extensions. They called for “those with old residencies to be taken into consideration, for updates not to be retroactive” and to “accommodate the transition of tourist residency holders to other types of residency, such as work residency and humanitarian residency.”

In their statement, they stressed the need to take unsafe countries, including Syria, into account in the matter of residencies, and for tourist residency permits to be accommodated for people from those countries.

“Personally, I still want to stay in Turkey, despite all the current circumstances,” Wissam said. Whether that will be possible remains uncertain.

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.