Aggression in last de-escalation zone risks fallout between Turkey and Russia

As Syrian government forces advanced in northwest Syria, opposition forces retreated and Ankara stepped up its military response and accused Russia of violating past agreements.

10 February 2020

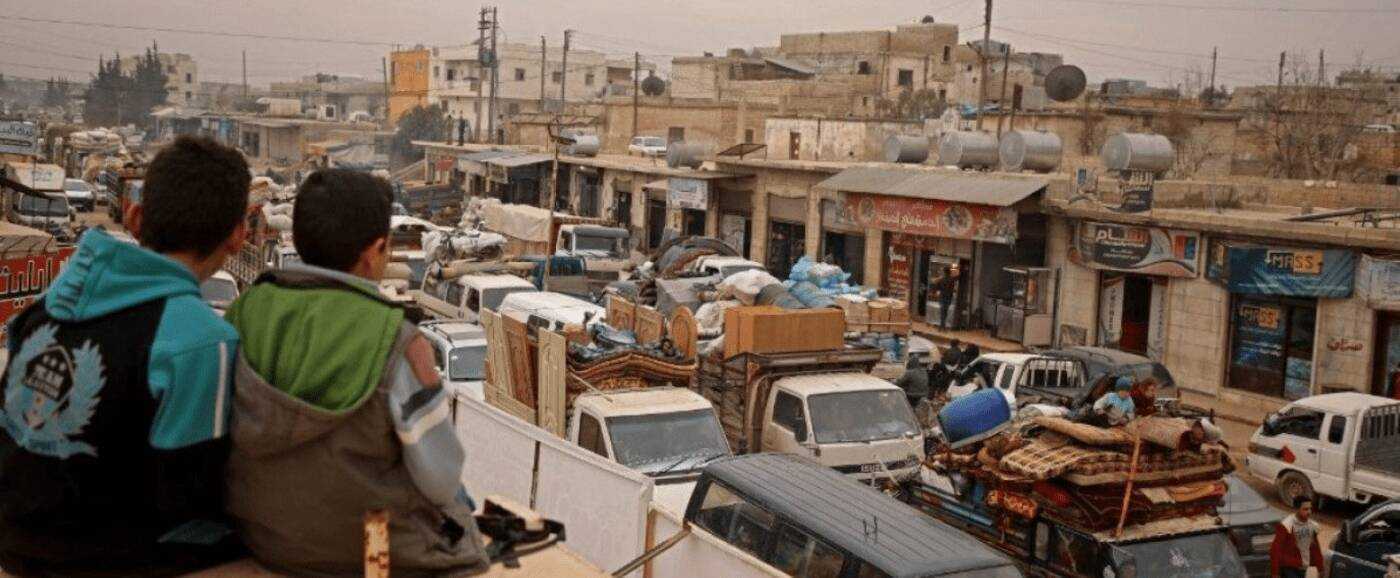

Two Syrian boys sitting on a ledge watch traffic in the town of Hazano in the northern countryside of Idlib, as people flee northwards amid a regime offensive, 4/2/2020 (AFP)

AMMAN — As Syrian government forces and their allied militias rapidly advanced on Maarat al-Numan in Idlib province in January, Ahmad Rashad Aboud and his family fled the city with a wave of newly displaced persons.

Despite an escalating government offensive taking place in defiance of a January 12 ceasefire deal between Russia and Turkey, Aboud resisted leaving Maarat al-Numan until the last possible moment, he told Syria Direct. But as the shelling increased, he vacated and drove 20 kilometers away to the nearby town of Marzaf to watch the unfolding events from a distance. He hoped and expected to return once the Syrian troops halted the fierce military campaign. They never did.

On January 28, nearly a month after Aboud’s departure, the government announced its take-back of Maarat al-Numan after a series of developments that resembled the fall of Khan Sheikhoun in August 2019.

As hundreds of thousands of civilians fled over months of bombardment, the Syrian government conquered the abandoned city. Traces of a once-vibrant civic and politically active public lie in the scraps buried beneath the devastated, graffiti-inscribed walls of a debris-filled ghost town.

Upon hearing the news, Aboud packed up once again and drove another 10 hours to resettle in the city of al-Bab in Aleppo province.

“I hoped international pressure would stop the escalation and allow civilians to return or factions to repel the army,” he said. “They [the factions] defended it, but a lack of coordination and organization prevented them from withstanding the aggression. A village or city would be burned and the stones, people, and trees destroyed, before the ground forces of the government enter.”

Almost 10 days later, and in spite of Turkish President Recep Tayyib Erdogan’s threats to use force if Syrian government forces don’t retreat, Syrian forces captured another key-opposition city in the countryside of Idlib province. Saraqeb, a city located at the intersection of Aleppo-Latakia highway (M4) and Damascus-Aleppo highway (M5), fell under the government’s control on Thursday, February 6. Within the course of a few days, government forces captured more than 52 areas in both the southern and western countryside of Aleppo.

The collapse of opposition resistance

Maarat al-Numan is the second-largest city in Idlib province after the city of Idlib. It is located on the international highway (M5), which is vital for the country’s economy. The city had a population of about 100,000 people before residents fled bombardment.

As Syrian government forces and their allied militias resumed their offensive on January 24, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a hardline Islamist group and the largest remaining military faction in northwest Syria that controls large parts of Idlib province, released a video in which senior jurist Abu al-Fath al-Farghali announced the group was willing and prepared to defend the city.

“Maarat al-Numan will never fail, God willing,” al-Farghali stressed in the video. “The situation is under control.”

Soon after, Syrian forces captured the city.

“No bullet was fired by HTS in Maarat al-Numan,” an opposition military commander in northwestern Syria told Syria Direct on condition of anonymity as he is unauthorized to speak to the media. He accused the group of withdrawing its heavy weapons from the city and its surrounding areas to the border towns with Turkey a week before the last assault by government forces began and was surprised to see HTS give up Maarat al-Numan “with such ease.” The group benefits financially from its local councils and zakat taxes through its so-called Syrian Salvation Government, he said.

Muhammad Abdul Rahman, who previously occupied a media post with HTS and requested his name be changed for his safety, affirmed that HTS withdrew its heavy weapons weeks before the pro-government forces began their recent military operation.

“That is why the areas were handed over one after the other without a fight,” he added. “Some HTS fighters broke away from the group and set out to repel the incursions in their towns, [while] some other groups affiliated with HTS were merely participating to ‘save face.’”

However, HTS media officer, Abu Khaled al-Shami, told Syria Direct that the rapid fall of the territories was “a result of the extensive and violent campaign launched by the Russian occupation forces.”

“The opposition [militant groups and HTS] had inflicted great losses among the enemy [government forces and their allies] during the past 45 days, killing more than 1,500, including more than 140 officers and some Russian soldiers, and wounding hundreds of enemy forces,” he added.

According to Elizabeth Tsurkov, a fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, there is a clear decision by the rebel factions to preserve their forces and avoid exhaustion in battles they know they will lose. As rebels realized they were unable to stop the government’s advances, particularly in flat areas, HTS’s strategy shifted to preserve its forces for the area they will control, Tsurkov told Syria Direct. The group has learned not to hold on to areas that are hard to defend and withdraw instead of losing forces.

“We saw this strategy clearly in previous stages of the offenses as well with them retreating from Khan Sheikhoun and Kafr Naboudah. HTS was deeply impacted by the experience of fighting Sharq al-Sikka [east of the railway] in Idlib, where they lost an immense number of fighters,” Tsurkov said.

“Since halting the advance does not depend on the strength of military resistance but rather on foreign decisions, HTS sees no point in wasting the lives of rebel fighters, particularly as the group suffers from a shortage of qualified manpower,” she added. “At the end of the day, they [HTS] understand the regime will continue to advance despite manpower losses. They understand this offensive will be stopped when foreign forces decide to stop it.”

Attacks in Aleppo

In contrast to the rapid fall of Maarat al-Numan, the fronts of the western countryside of Aleppo were defended with fervor. The Turkish-sponsored Syrian National Army (SNA) and HTS launched two separate military operations against Syrian government forces in the eastern and western countryside of Aleppo province on February 1, curtailing their advance in the area for 10 days.

“The SNA launched a military operation from the city of Tadef in the countryside of the city of al-Bab in northeast Aleppo and managed to briefly control a few villages west of the city of al-Bab,” Nasr al-Akal, a member of the media office of the SNA-affiliated National Front for Liberation (NFL), told Syria Direct.

On the same day, HTS detonated two car bombs targeting sites of Iranian militias and government forces in the western countryside of Aleppo, according to the group’s account on Telegram.

Opposition-affiliated local media outlets reported that HTS and the Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement reached an agreement on January 29. Through the agreement, HTS permitted an armed group from al-Zenki to cross the northern countryside of Aleppo to the western fronts that were under their control before HTS expelled them in January 2019.

However, the attacks in the countryside of Aleppo sparked controversy over their real goal.

“The elite forces [affiliated with HTS] that participated in the military action in the western countryside of Aleppo had been transferred from the fronts of Al-Kabinah [in the Al-Haffah District in Latakia countryside],” the opposition military commander in northwestern Syria said.

“Why did HTS send them to Aleppo instead of Idlib to repel the attack there?” he asked. “Some say [Turkey] is liable. That it wants to send political messages to Russia. And I say that HTS owns the land, the weapons, and has the final word. It allowed the area to be captured. In the end, the guarantor only cares about its interests.”

However, Tsurkov argued that “the terrain in Aleppo is much more favorable for combat. It’s built up and therefore makes much more sense to hold on to territory there.”

“In general, people are frustrated and looking for someone to blame,” she added.

In addition, Muhammad Sarmini, director of Turkey-based Josoor Center for Studies, stressed that the operation carried out by the SNA east of Aleppo is directly linked to the movements of the government forces there. The opposition factions expected the fight with the government forces to spread, he told Syria Direct.

Is this the end of the Astana Talks?

As a result of the Astana Talks sponsored by Russia, Iran, and Turkey, Idlib turned into a so-called de-escalation zone where acts of aggression are prohibited. However, the ceasefire has been routinely violated.

Recently, President Erdogan has accused Russia of violating past agreements to reduce fighting in Idlib, while Moscow blamed Turkey for failing to fulfill several key commitments, including withdrawing armed opposition groups from the demilitarized zone agreed upon in Sochi.

After two Turkish observation posts fell behind the Syrian government frontline and eight Turkish military personnel were killed as government forces advanced in Idlib province, Ankara sent additional troops into the region and threatened to respond if its military observation posts, set up under the 2018 truce, come under attack. Turkish military struck dozens of Syrian government targets, killing between 30 and 35 Syrian troops.

The Turkish president called the latest escalation a “turning point in Syria for Turkey.”

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) reported that more than 1,240 Turkish trucks and military vehicles arrived in Syria, carrying tanks, personnel carriers, armored vehicles, mobile bulletproof guard booths and military radars between February 2 and February 8.

According to Ahmed Hamadeh, a military and strategic analyst, what is transpiring on the ground jeopardizes the future of the Astana Talks. Turkish military reinforcements and the establishment of four new observation posts surrounding Saraqeb is evidence of this, he told Syria Direct. Ankara’s decision regarding its observation posts is critical at this stage, as Erdogan has kept the door to military options wide open.

By that same token, Erdogan announced the Astana Peace Process had “crumbled” in late January, and called on Russia and Iran to revive the talks. Turkey is concerned about the humanitarian effects of Russia’s unyielding violence but is trying to preserve negotiations with Moscow and avoid direct clashes, Sarmini said.

Russia, on the other hand, aims to have the “greatest geographical control while maintaining its negotiating relations with Turkey … it also wants to maintain the Astana framework and the Sochi Agreement,” he added.

Earlier, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that he maintains contact with Turkey on the situation in Syria and recalled the existing agreements between Moscow and Ankara as well.

“I would like to underscore again, considering all the factors I’ve mentioned, Russia cannot solve this problem alone, but it can fight for unconditional and meticulous fulfillment of agreements on Idlib. This is what we’re talking about with our Turkish partners,” Lavrov said.

A version of this report was published in Arabic and translated into English by Nada Atieh.