Idlib camps increasingly permanent despite ‘dream of return’

Thirteen years after the Syrian revolution, displacement camps in Idlib’s Atma look increasingly like towns, tents replaced by cement buildings. Has the dream of return been lost?

18 March 2024

PARIS/IDLIB — “Every moment, we dream of returning home. We hope our stay in the camp will be temporary, not permanent,” Mazen al-Wared began. When he first arrived in this displacement camp 11 years ago, he lived in a tent, battered by the winter wind and scorched by the summer sun. As years dragged by, the tent became a cement house, one that resembles the home he fled.

Al-Wared, 40, lives with his family of nine in the Umm al-Shuhada camp, one of scores of informal camps in the Atma border area between Syria’s northern Idlib countryside and Turkey. They fled their village in the southern Idlib countryside in late 2012 to “escape indiscriminate shelling and incursions by Syrian regime forces at the time,” he told Syria Direct.

Umm al-Shuhada, established by families like al-Wared’s who fled bombings in 2012, lies in a strip of no-man’s land between the Syrian and Turkish borders. The informal camp is one of around 105 similar camps making up what is known as the Atma cluster, home to hundreds of thousands of people displaced from different parts of Syria.

Thirteen years after the March 2011 revolution, the spark that set off a chain of events that ended in the prolonged displacement of the people living in Atma, the area looks more like a collection of small, informal towns—lacking organization and infrastructure—than a group of camps. Canvas and plastic tents, signs of a temporary stay, have given way to cement bricks.

Mazen al-Wared, 40, stands on the roof of his house in the Umm al-Shuhada camp in the Atma region on the Syrian-Turkish border, 10/3/2024 (Abd Almajed Alkarh/Syria Direct)

From tents to brick houses

Like other displaced Syrians, al-Wared lived in a shabby tent in Atma for several years, his family holding on to the “hope of returning to our village,” he said. As the years dragged by, however, he bought blocks and cement, then built a house brick by brick.

Tents flooded in the winter, and the lack of a road network in the camp meant vehicles could not enter, especially emergency vehicles. These conditions pushed people towards “trying to settle down again in modest cement houses,” he said.

Seven years ago, Kusiya Ahmad al-Qaws, 65, fled regime bombardment of her village in the Sahl al-Ghab area of the Hama countryside alongside her sons, daughters and grandchildren. The family settled in the same camp where al-Wared lives, at the time still a group of tents.

When al-Qaws and her family arrived, they sheltered under the branches of nearby olive trees at first, until they finished setting up a tent of their own, she told Syria Direct.

Years later, “people started to buy bricks and replace the tents with small rooms with plastic roofs and poured cement floors,” al-Qaws recalled. Her family followed suit, building a modest cement house in the camp at a cost of $200 per room.

Kusiya Ahmad al-Qaws, 65, sits in front of her house in the Umm al-Shuhada camp in the Atma area of northwestern Idlib province, 10/3/2024 (Abd Almajed Alkarh/Syria Direct)

While seven years have passed and al-Qaws’ tent has become a cement house, she has not forgotten the difficult early years of displacement. “Life was hard, we couldn’t move about or go buy what we wanted,” she recalled. One day, “my daughter-in-law went into labor, and there was no car in the camp. She had to walk more than a kilometer to reach a car to take her to the hospital, and she went through a lot of hardship walking.”

Shops at the entrance of the informal al-Jazira displacement camp, part of the Atma camps cluster on the border between Idlib and Turkey, 10/3/2024 (Abd Almajed Alkarh/Syria Direct)

“Today, the camp has vegetable shops, grocery stores, barber shops and pharmacies, and cars enter it,” al-Qaws said. The camp has become like “a village,” and the painful early days have become “memories.”

Al-Wared, too, recalls painful memories from his early days in the camp. Once, his son fell ill and he had to carry him on foot to the neighboring town of Atma, searching for a doctor to treat him. At the time, ambulances could not enter the camp.

Another time, a fire broke out among a group of tents in the Umm al-Shuhada camp. Residents called the civil defense, but “the fire trucks arrived late because of the road, so people had to put out the fire themselves,” he remembered.

Today, “the camp has significantly developed, and services have gotten better: the road network, medical services and drinking water,” al-Wared said, likening them to “city services.”

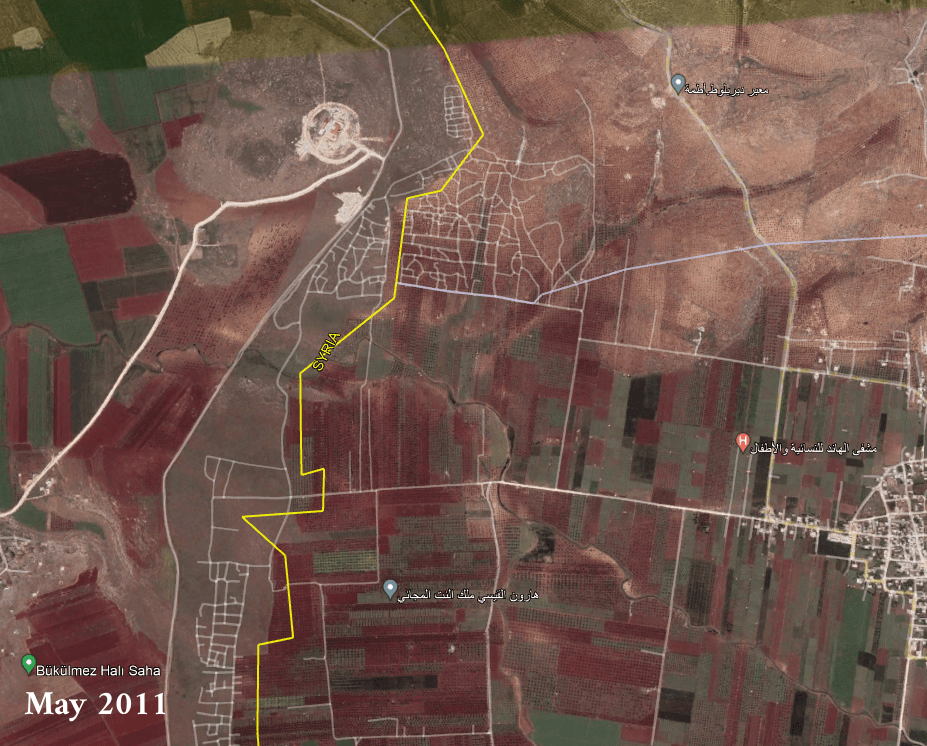

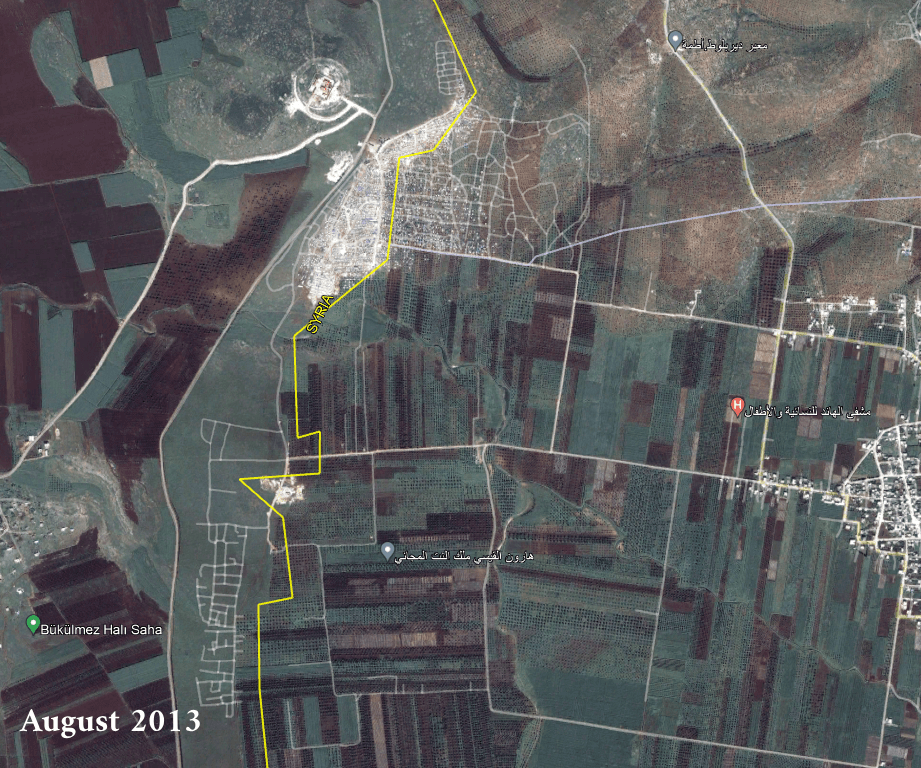

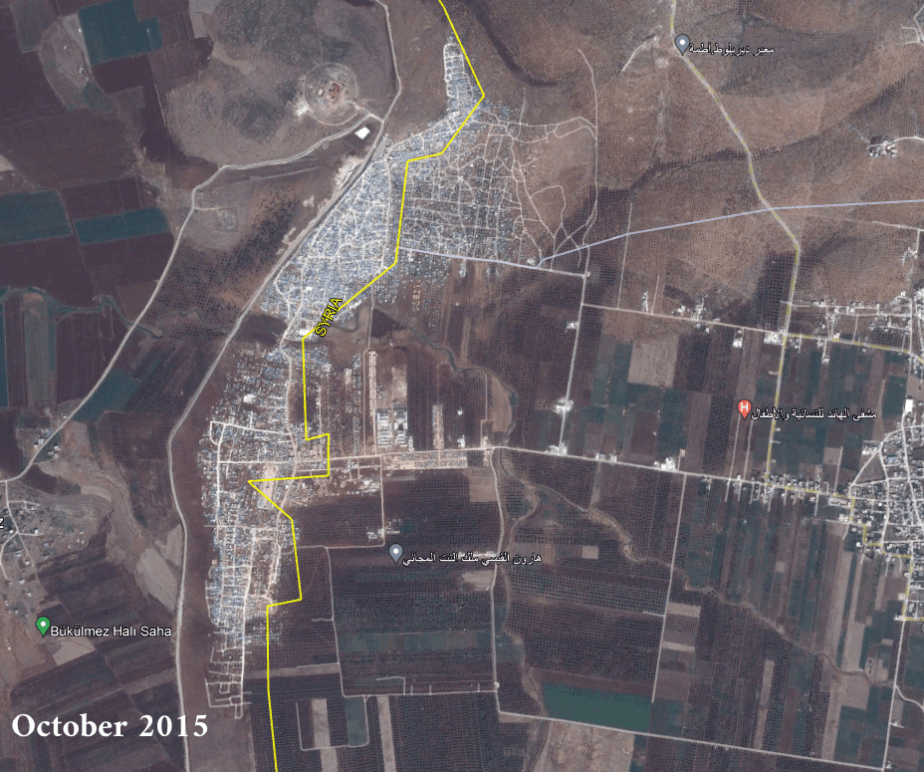

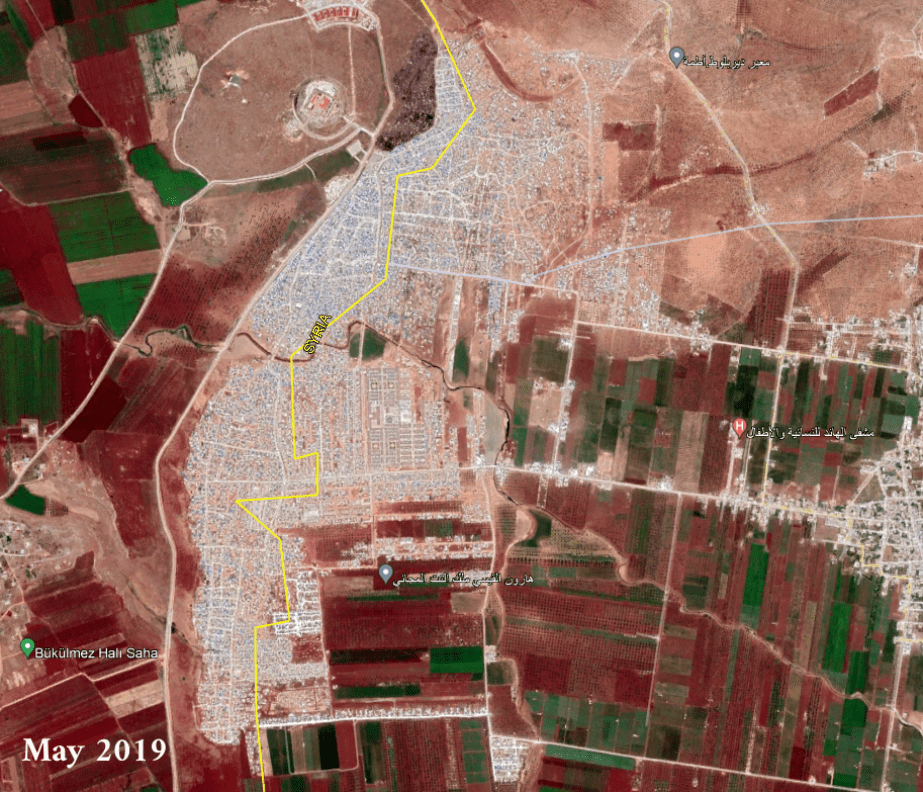

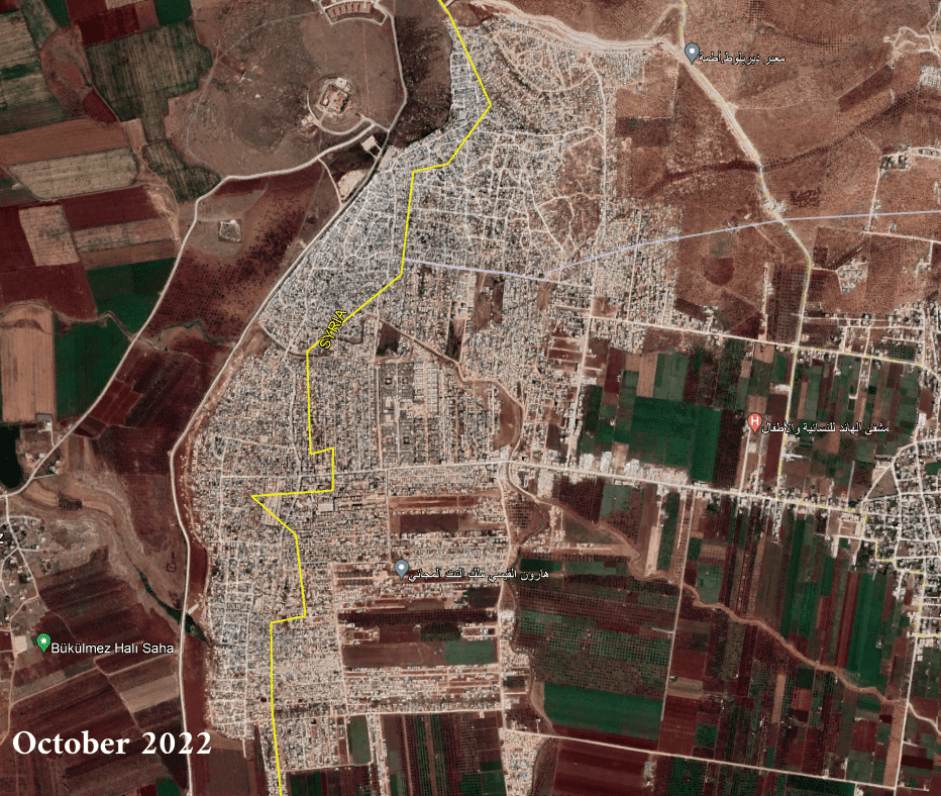

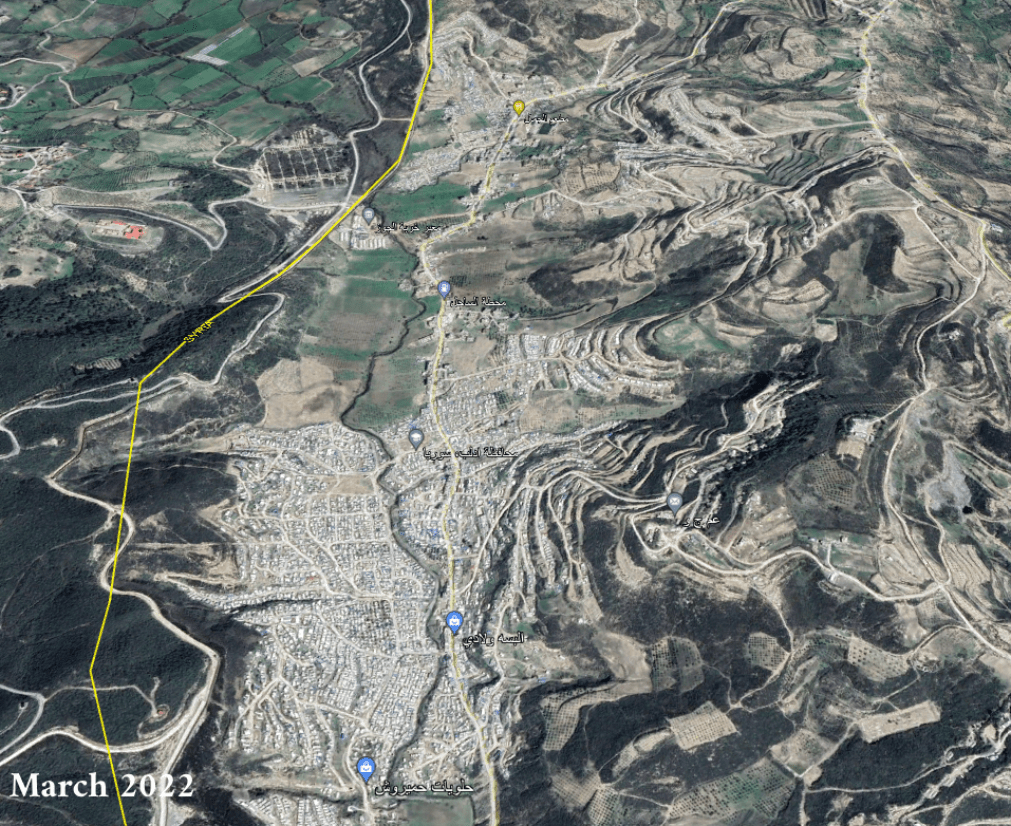

Satellite images show the transformation of the Atma camps on the Syrian-Turkish border—from farmland to tents to concrete buildings—between May 2011 and October 2022 (Google Earth)

Birth of Atma

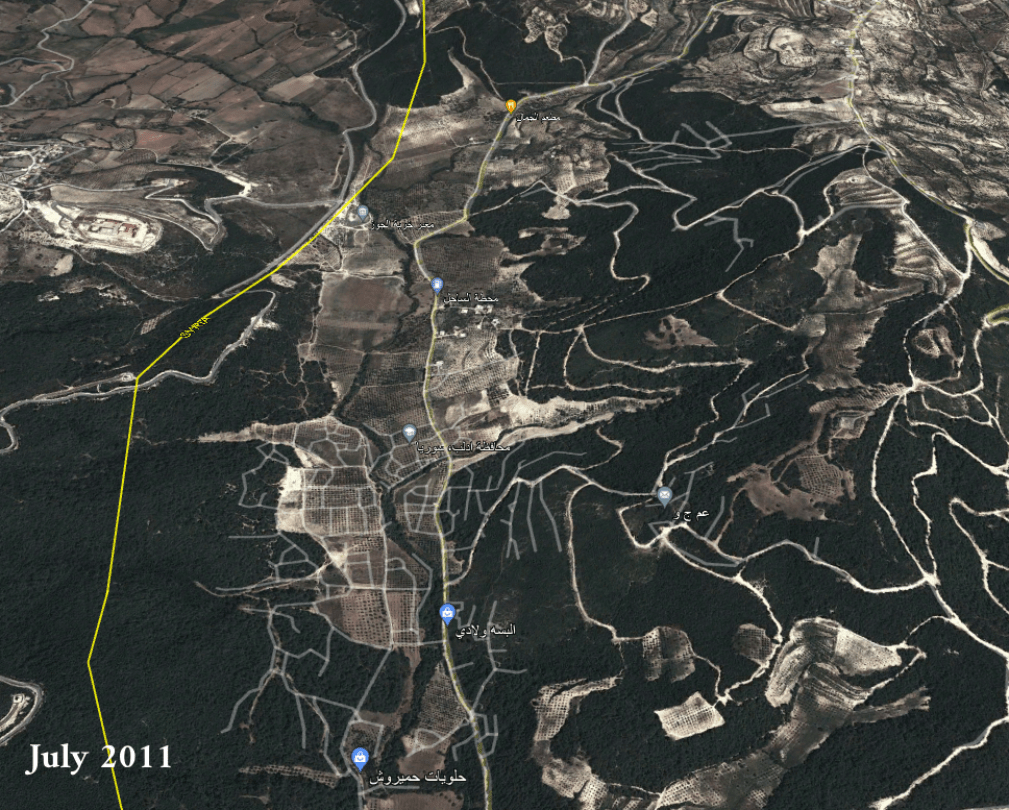

The Atma camp cluster began as a group of tents inside the strip of no-man’s-land between Syria and Turkey in 2012, then gradually expanded into Syrian territory.

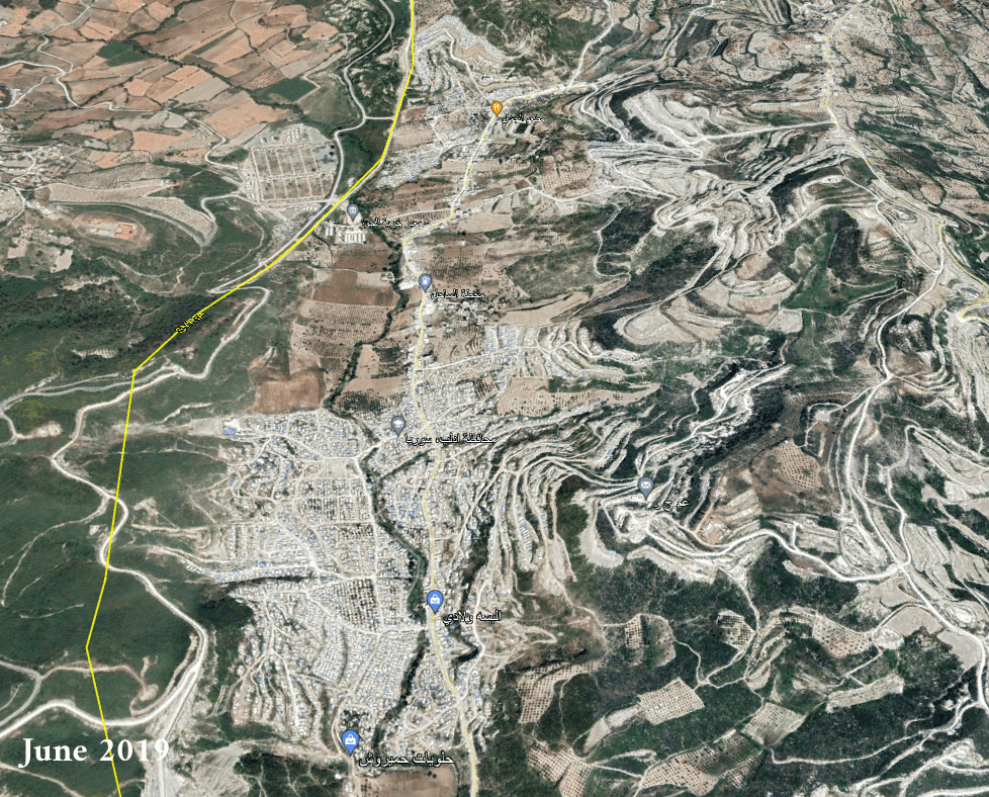

Over the past 12 years, informal settlements have crept from the border strip and the Turkish separation wall into Atma’s farmland and olive groves, stretching all the way to the town of Atma. With each new wave of displacement, the camps grow.

Traders took notice of the displacement, and turned it to their advantage, buying up farmland in the area, Muhannad al-Muhammad, a journalist living in Atma’s Northern Homs Countryside camp, told Syria Direct. “It was a profitable business for traders who bought the land, divided it up, opened roads then offered it for sale and rent.”

When al-Muhammad was displaced from the northern Hama countryside to Atma, the camp where he now lives had only around 40 tents, among 350 cement houses roofed with slabs of cement or nylon siding. One year later, “plastic roofs were replaced with slab roofs, and the remaining tents turned into cement houses,” he said.

Today, “only four tents remain,” al-Muhammad added. “Many shops, markets and multiple-story buildings are scattered throughout the Atma camps.”

An aerial picture of al-Jazira camp, part of the Atma cluster of informal displacement camps just inside the Syrian-Turkish border, 10/3/2024 (Abd Almajed Alkarh/Syria Direct)

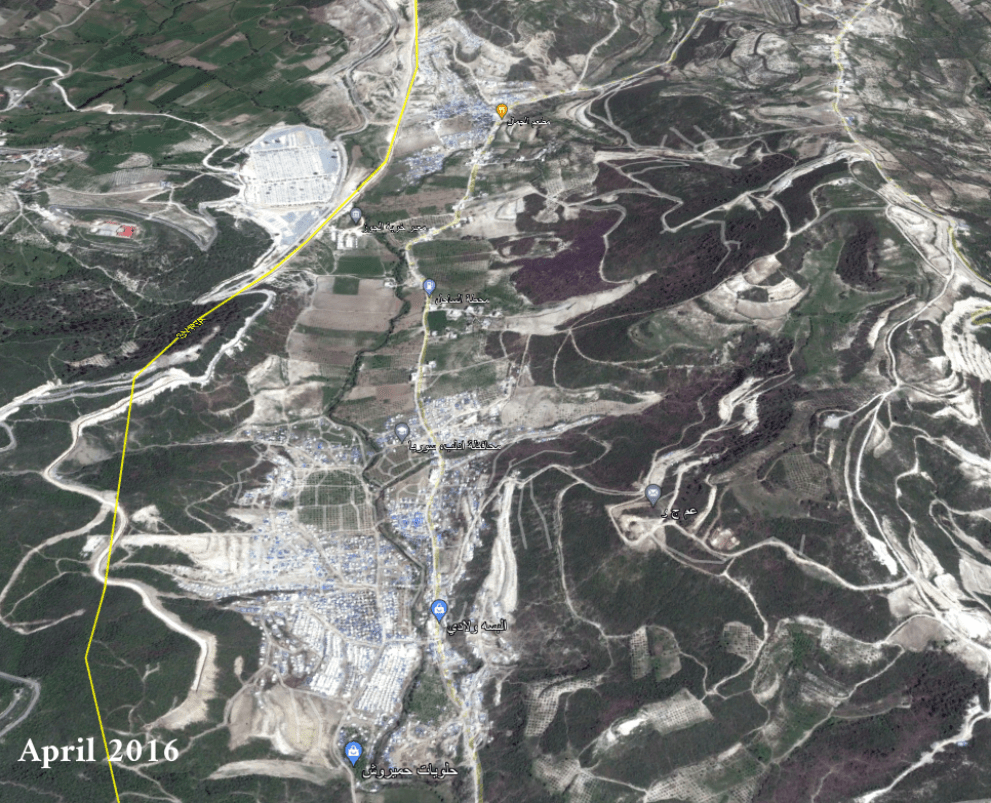

Al-Jazira camp, the oldest in the Atma area, was established in early 2012 by people displaced by regime bombing of the northern Hama countryside and the Jabal al-Zawiya area of Idlib, the camp’s director, Ibrahim al-Yusuf, told Syria Direct.

Al-Jazira, which sits on the no-man’s-land between Syria and Turkey, went through a similar transformation to other camps in the area over the past 12 years. Around three years in, “people started to get rid of the tents and build cement houses in their place,” al-Yusuf said. “They knew it was going to be a while.”

Ibrahim al-Ibrahim, the Director of Atma Development within the Salvation Government—the civil face of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the faction that controls most of Idlib—said the idea of camps in no-man’s-land began in April 2011, since it was a safe area.

“These camps consisted of tents that did not protect their inhabitants from the winter cold or summer heat, in areas with rough roads. They were not organized and had no services,” al-Ibrahim said. “Then, over the past years, some projects provided services.”

Most of the Atma camps were established on private land, or land purchased from people who left Syria. Around a quarter sit on public land. “Some private land is illegally occupied by displaced people, and work is being done to move them to other residential blocks and return the land to its owners,” al-Ibrahim said.

Ibrahim al-Yusuf, the director of Atma’s al-Jazira camp, stands next to the Turkish border wall, 10/3/2024 (Abd Almajed Alkarh/Syria Direct)

Informal ‘cities’

After journalist Muhammad Hamza was displaced from his southern Idlib countryside village in 2019, he purchased a 50-square-meter plot of land in one of the Atma camps, where he built a two-story house. Since then, living conditions have improved.

Last year, the Atma camp cluster saw a “major project by one of the humanitarian organizations to extend a drinking water network as an alternative to tanked-in water, and reached most of the camps,” Hamza told Syria Direct. A sewer network was also built in some camps.

Projects such as these have helped improve conditions in the Atma camps, but “they are still essentially random residential blocks stuck together, with brick walls, plastic insulation and narrow streets,” Hamza said. Atma is “a city in terms of its population, but lacks planning and organization.”

The camps are disorganized because “building in them doesn’t require a permit,” Hamza said. As a result, they have come to resemble “the informal neighborhoods of Damascus and its countryside,” he added.

“Encroachments on the streets in Atma are continuing, and there is no organization,” al-Muhammad, in the Northern Homs Countryside camp, added. He accused the Atma Services Administration of “negligence in administrative organization and infrastructure” and “existing to live off aid, not to organize.”

For al-Wared, however, “the camp is a city, and more,” as he put it. “It has a large number of people, commercial interests, shops and markets.”

Al-Qaws said “the camp is like the village” she lived in before she was displaced. She feels it is “much better than it was years ago.”

While building has expanded in the Atma cluster and commercial centers have spread, “it can’t be said that it has turned into cities, because they are camps that lack the most basic means of life,” development director al-Ibrahim said. There are some exceptions, “camps that can rise to [the level of] being villages, given the urban organization and services in them. These are camps whose construction was overseen by some humanitarian agencies.”

The Salvation Government’s Directorate of Atma Development does not want the camps to become informal cities. To avoid that, it has developed a “service plan to organize all the informal camps, and seeks to reach the point of removing all the tents and moving people into residential blocks, according to the capabilities available, in partnership with humanitarian bodies,” al-Ibrahim said.

To that end, “we have formed an administration committee for each camp, which oversees statistics and raises humanitarian needs to the directorate in order to carry out the needed service projects alongside our humanitarian partners,” al-Ibrahim added. Work is being completed on sanitation, road-paving and water network projects, he said.

Satellite images show the development of the Khirbet al-Joz camps on the Syrian-Turkish border from July 2011 to March 2022 (Google Earth)

Memories of home

The land al-Muhammad has built his house on is still in the name of the trader he bought it from. He received a sale contract, but has not transferred ownership in the Salvation Government’s records.

Al-Muhammad could easily “transfer ownership of the land in the official register after paying a $100 tax, but I don’t intend to settle down here,” he said. It worries him that “everything is moving towards these camps being a permanently settled area” because he is waiting to return to his village in the Hama countryside.

Some of his neighbors in the camp can go home, but are staying in Atma for now. “Their areas have been liberated [from the regime], but they are still in the camp. It has become a zone of stability for them, because the regime periodically shells their villages, because they have lost everything there or because of economic reasons—getting aid in the camps,” al-Muhammad said.

Mazen al-Wared, 40, stands with two of his neighbors in a neighborhood of Atma’s Umm al-Shuhada camp, 10/3/2024 (Abd Almajed Alkarh/Syria Direct)

As al-Wared sees it, the camp may be “a city and more,” but he still expects to “return one day.” It is not currently an option, but when that hoped-for day comes, “I will sell the house at cost, because the land is public—in the no-man’s-land—and I can’t sell it,” he said.

Al-Yusuf, the director of the al-Jazira camp who also lives there, believes most of its residents “would leave and return to their native villages if they were liberated, even if they have built a castle here.”

“We tell our children that these camps are temporary, that we will return home one day, no matter how much we build houses or open stores in the camps,” he added.

Al-Wared does the same, describing “the village and our life there” to his children, especially because some of them were born in the camp.

Al-Qaws, a grandmother, tells her children and grandchildren all she remembers “about the village, the land, our life there,” she said. “We pray to God to return.” The camp may be like a village, but “it is not our land,” she added. “One day, we will return to our villages and farms, and rebuild our homes once more.”

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.