Aleppo neurosurgeon on the frontline: ‘Textbooks never prepared us for the injuries we see’

Since the Assad regime’s first attack on a medical facility […]

11 January 2016

Since the Assad regime’s first attack on a medical facility in Aleppo on July 30, 2012, just one week after rebel forces gained major ground in the city, human rights organization Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has documented 336 attacks on medical facilities and the deaths of 697 medical personnel, according to a recent PHR report entitled “Aleppo Abandoned.”

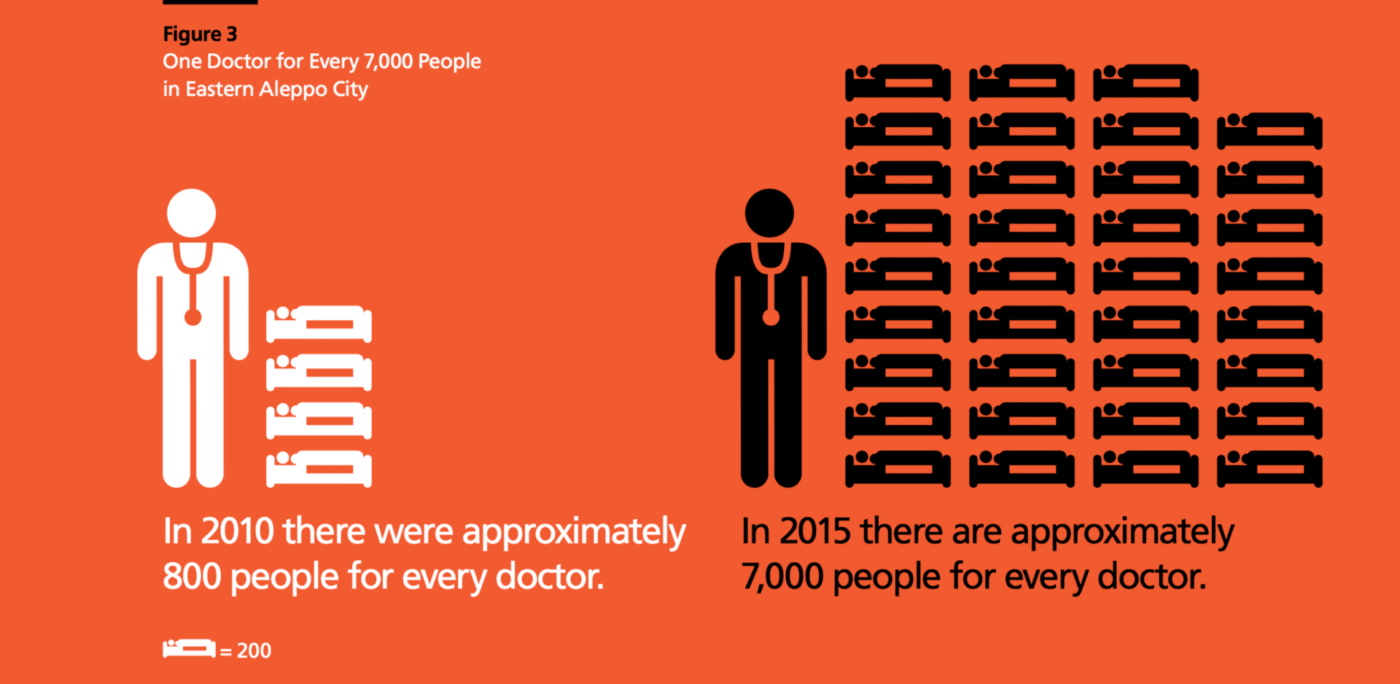

With only 10 of the 33 medical facilities in Aleppo city currently functioning and approximately 95 percent of doctors having fled, been detained, or killed, PHR calls on the international community to end its “indifference,” Donna McKay, the executive director of PHR, tells Syria Direct’s Samuel Kieke.

“There has probably never been a war better documented in real time as we are seeing in the Syrian conflict, so it is not for a lack of evidence or story telling – it’s actually for a lack of political will,” says McKay.

The number of attacks against health professionals in Syria is “unprecedented” in human history, she says. The deliberate targeting of medical infrastructure is “a weapon in Assad’s arsenal” to “strangle the civilian population by denying them basic healthcare at a time when the community needs it most,” says McKay.

Photo courtesy of Physicians for Human Rights.

“The regime targets medical facilities everywhere because it knows that they are the key to survival,” Dr. Rami Kalazi, one of two remaining neurosurgeons in Aleppo city and one of the 24 medical personnel interviewed by PHR for their report, tells Syria Direct’s Ghardinia Ashour. “Without them, life stops.”

Dr. Kalazi was born and raised in Syria’s second city and is one of the 70 to 80 physicians still working to provide healthcare to the approximately 300,000 residents of rebel-held Aleppo.

After graduating from Aleppo University’s School of Medicine in 2009, Dr. Kalazi began his residency at the regime-run a-Razi public hospital in western Aleppo city where he met his wife, an endocrinologist who was doing her residency at the same time.

In March 2013, eight months after rebel forces seized the city’s northern, eastern, and southern districts, Dr. Kalazi and his wife, Dr. Jadaan, started secretly working at in a field clinic in the rebel-held northeast Aleppo neighborhood of a-Sakhur.

“The a-Sakhur neighborhood is one of the most targeted neighborhoods because of the clinic,” says Dr. Kalazi, adding that the clinic itself has been bombed 35 times.

The types of injuries the doctor and his colleagues treat are like none in medical textbooks. A piece of shrapnel can generate a dozen different wounds in the body, all urgent.

Dr. Kalazi describes an example: “When a piece of shrapnel enters the face and exits through the brain, the bullet causes injuries all along its trajectory: in the jawbone, the teeth, the tongue, the esophagus, the nose, the eye, the brain. So you have multiple injuries and there is only a narrow window of time in which you can treat all of those injuries at once.”

Below, part one of Syria Direct’s two-part interview in which Dr. Kalazi shares his not only experiences as a neurosurgeon on the frontlines, but why he stays in Syria.

Q: In the report that PHR published, it mentioned that medical personnel have seen unimaginable injuries that they never heard of or learned about before. What does it mean to be a wartime doctor? How are you tested when confronted with a case that you never saw before in your textbooks?

The most difficult situation that we encounter is massacres, when many injured people and martyrs come to us at once, especially a large number of children. Unfortunately, in any massacre, over half of the martyrs and injured are children. The injuries are mostly critical injuries. You might find a child whose body has been severed in half, decapitated, one who has lost limbs or lost an ear or an eye, or maybe he is crippled because of critical injuries. Truly, these are the most difficult times for us. Not because of exhaustion, but because of emotional stress–we sympathize so deeplywith wounded children. When confronted with an injured child, I often feel helpless.

We have some people who have become experts, especially after four years of working in field hospitals, particularly in general surgery, orthopedic surgery and thoracic surgery. These are the specialties of our hospital (a-Sakhour). I don’t know about other hospitals.

In the beginning, we saw new injuries that we did not know how to treat. Fortunately, at the beginning of the revolution and when we began working in field hospitals, there was more freedom of movement. In 2012 and 2013, there was no such thing as “barrel bombs” and there was no violent shelling from airplanes, so many visiting foreign doctors came.

Qualified experts from the Arab world and other countries taught us techniques that we did not know and personally trained us in treating fairly complicated injuries. But even so, they told us that they were seeing injuries that they had never seen before in books or textbooks or in the hospitals where they worked in their home countries. Unfortunately, reality forces you to learn.

Q: Can you describe one of these unimaginable injuries?

There was a young woman in her thirties with a shrapnel wound. Based on the entry wound, the shrapnel was not very big. The entry wound was on the inner thigh, around the pelvis and the abdomen. As you can imagine, this caused injuries to the bowels, and tore the uterus, bladder, rectum, and the aorta in the stomach. This caused extensive damage in the intestines and damaged the kidneys. You will never see this type of injury in textbooks.

They tell you that there might be one or two injuries, or three at most. If there are more than three injuries, the books tell you that the injury is fatal. With this case, we had about 10 separate injuries from one piece of shrapnel. Thank God, we were able to treat most of the injuries, but unfortunately in the end, due to the intensity, the patient passed away. These types of cases are frequent and we see many of them.

When a piece of shrapnel enters the face and exits through the brain, the bullet causes injuries all along its trajectory: in the jawbone, the teeth, the tongue, the esophagus, the nose, the eye, the brain. So you have multiple injuries and there is only a narrow window of time in which you can treat all of those injuries at once.

For children, the situation is very difficult, because children are much less able to withstand and recover than adults, which means that such injuries are usually fatal for a child.

Usually, with these kinds of unimaginable injuries, such as a body torn in two or when all four limbs are severed, injuries that cannot be treated, the victim dies before he gets to the hospital.

Q: Why are medical centers targeted in Aleppo more so than in other locations?

The answer is twofold:

In general, the regime targets medical facilities everywhere because it knows that they are the key to survival. Without them, life stops.

The second reason [for the targeting of the medical infrastructure] is part of the strategy that the regime follows. It appears that it focuses on Aleppo, more than other locations, for many reasons. Firstly, the city has a large population. Secondly, it is near the Syrian-Turkish border.

There are some Shiite-majority villages around Aleppo, and for that reason Iran has more influence [in Aleppo] and thus a greater desire than the regime to retake control of Aleppo. Medical facilities in Aleppo are therefore targeted more so than in other areas.

Q: How do you balance between caring for the sick and wounded and caring for yourself?

I’ve lived through a lot of airstrikes. During them I was inside the hospital and thank God I haven’t been injured. This makes me feel braver. I am someone who is resolute to stay in Syria. Others may feel afraid and in danger. That fear will justify their decision to leave Aleppo and go to the [Turkish] border, perhaps even leave Syria completely. We definitely know that we are targeted, but the airstrikes we have lived through increase our resolve.

As for the idea that we have to feel safe in order to make others feel the same, I don’t believe that is necessarily true. Safety is not equivalent to happiness. If you don’t feel happy, you won’t be able to make others happy, but I can make others feel safe in that the hospital is secure and fortified as much as possible. We take preventative security measures as much as we can, such as reinforcing [the structure of the hospital] and working underground.

Unfortunately, we face many difficulties, the largest being a lack of monetary aid. I try and provide all of the medical services that the injured need as best I can. Consequently, they feel safe because they know that they are surrounded by people who care for their well-being.

Q: Describe your daily routine. When do you begin work? How long do you work?

Our shifts at the hospital last between 15 and 20 days and we have 10 to 15 days off in between. However, if something serious happens, we are always on call.

Over these 15 days on shift, our work doesn’t stop until late at night because regime and Russian warplanes are continuously dropping bombs.

Normally, there are at least one to two specialists from each field on duty, but some specialists [in certain medical fields] don’t need to be available 24 hours a day over the course of 30 days (such as plastic surgeons or even orthopedic surgeons).

We neurosurgeons are always on duty. Each of us works 15 days, then the other will work the following 15 days. This is the case for general, vascular and thoracic surgeons as well. The number [of surgeons in each field] is limited, but we try and manage with whomever is available.

Generally, I have 10 to 15 days of leave and I can go to Turkey or we can attend training courses to further develop our skills and get away from the stress. Merely sitting in the house or spending time with colleagues outside work gives us some relief.

The longest period of time I spent on duty was 21 consecutive days. There wasn’t any other doctor to take my place, so I had to stay on duty as long as I could because the regime was targeting Aleppo more than usual at that time. I’ve had to work for 21 consecutive days once or twice, but general surgeons have to do this on a regular basis.

In my field, neurosurgery, we can treat some cases, but others we transfer on [to Turkey]. Generally, serious injuries are fatal. For that reason, we don’t perform a lot of neurological operations. However, I like to help with general surgical operations.

When there are massacres that involve a lot of injuries, I assist the orthopedic surgeon that is on duty since there are only two of us who alternate shifts. I remember that one time we worked for 40 consecutive hours without even noticing how much time had passed.

Q: If you are forced to choose between treating someone who is sick that you think is untreatable and someone who you think could possibly be helped, whom do you choose? How do you feel when forced to choose who will get treatment?

We might initially try to treat the severe injury for five minutes, during which we determine if there is a possibility to save the patient or not.

Generally during those five minutes, if the vital functions fail, then he will be brain dead. Even though he continues to live, he will be in a vegetative state and clinically dead. In those instances, we choose to move on to other patients who we can more likely treat successfully. It is a difficult decision. We feel severe sadness when we are forced to make that choice, but this is part of triaging.

Q: So you agree with the principle of mercy killings?

Yes, in the worst cases I am in favor of it, unfortunately.

We do not make this decision unless we are forced to do so and there is no other option. For example, if we have a patient who needs to be on a respirator but we only have three or four such devices.

If they are all being used by other patients and one of those patients has been on a it for a long period of time and we know that recovery is unlikely, then we may decide to take him off life support. This is only if we have run out of all other options to save him, including communicating with other clinics to see if they have an available respirator, and trying to transfer him to Turkish clinics.

If we have two new cases and one of them has a 90 percent or higher chance of dying and the other has a 50 percent or lower chance of dying, then we try to resuscitate the individual with a 90 percent or higher chance of death for five to six minutes. But if he doesn’t make it, then we can’t give him any more time because there is the other patient waiting.