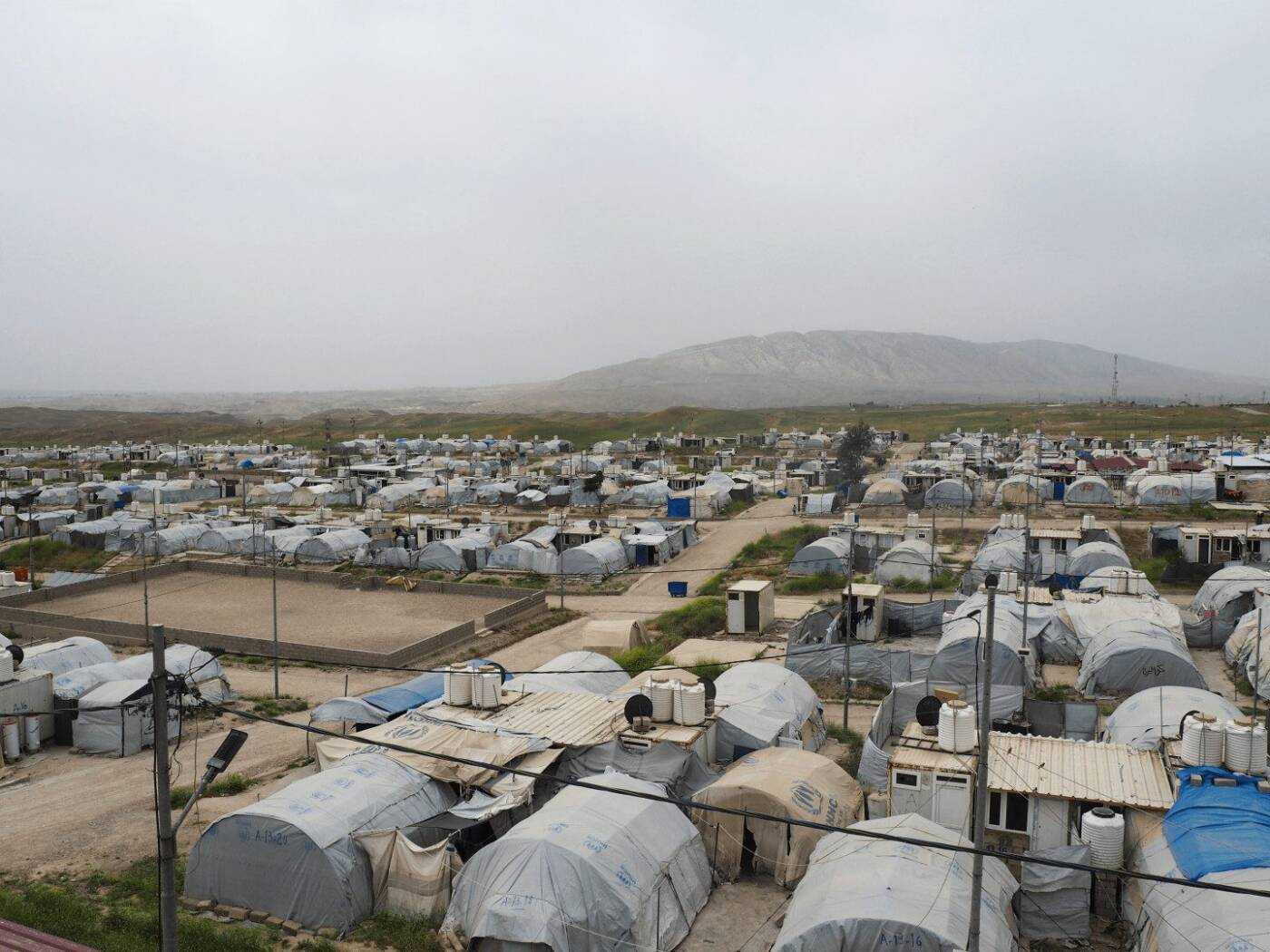

Bardarash camp in Iraqi Kurdistan: Those who remain behind

After ‘Operation Peace Spring,’ over 11,000 Syrians fled to Bardarash refugee camp in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Only 3,500 remain; why?

20 June 2021

DUHOK — Empty Nutella jars filled with spices stand perfectly ordered on the kitchen shelf. Onions are growing in the garden. Hemrin turns on the fan while she sews the flowery clothes that her husband, Mahmoud, sells in their shop. Their three daughters play in the living room.

It feels like home, but it is not.

Hemrin’s family is one of the 830 Syrian refugee families living in Bardarash camp in northern Duhok province in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). Under a dusty sky, the fenced camp is surrounded by kilometers of vast empty greenery.

Bardarash camp was first opened to host internally displaced Iraqis from the ISIS war in Iraq (2014-2017). In late 2017, the camp closed, only to reopen in October 2019 as a part of a broader response to deal with the 17,000 Syrians from northeast Syria (NES) who were displaced by the Turkish-led ‘Operation Peace Spring,’ when armed groups backed by Turkey took control of border areas in NES.

In total, Iraq hosts 247,305 Syrian refugees, most of them Syrian Kurds who live in KRI. At its peak, in December 2019, Bardarash camp was home to 11,000 Syrian refugees.

Today, only 3,541 refugees remain in the camp. It feels like an empty shell: there are 1,810 vacant shelters and only 878 occupied shelters. To date, 13,986 individuals have left the camp and moved to cities in KRI after obtaining residency permits, while 1,488 have returned to Syria, Hassan Mohamad Zabar, Deputy Camp Manager, told Syria Direct.

The 830 families that remain are the ones that didn’t get residency permits yet, or don’t have the means to afford the cost of living in a city.

Refugees get temporary permits from the authorities to go out of the camp to work or visit people outside. To move out of the camp permanently, they need a residency permit. “If they want to leave the camp to Syria or KRG provinces, we have a process where the Asayish [Kurdish security forces] give the approval, and they leave the camp officially,” Zabar explained.

‘We can’t go back to Syria’

Hemrin, Mahmoud and their three daughters sit in their tent in Bardarash camp, 21/04/2021 (A. Medina, Syria Direct)

For Hamrin’s family, ‘home’ is a tiny village next to Ras al-Ayn in northeast Syria, where they used to cultivate their land. They fled to KRI soon after the Turkish-backed groups entered Ras al-Ayn in October 2019.

“We came here because it is safe,” Mahmoud said. “Electricity, water, the tent, all is provided; living in this camp is better than being left with nothing,” Hemrin added.

Like the rest of the inhabitants of the camp, each member of the family gets 24,000 Iraqi dinars (IQD) per month distributed by the World Food Program and the INGO World Vision. In their case, with five members, it amounts to approximately $85 per month. To complement this assistance, they have a small clothes shop in the camp.

“With the small children, I can’t leave to work outside the camp; we don’t have anyone here to take care of them. I sew here, and [Mahmoud] sells; it is ok like that,” Hemrin said.

Their residency permit is still in process. They could ask for permits to leave the camp to work, but they cannot afford the high transportation costs: the closest cities are Erbil and Duhok, 80 and 100 kilometers away, respectively.

“Outside the camp, life is difficult; you need money, and due to corona, work is scarce,” Hemrin said. “I just want to go back to my house, nothing more,” Mahmoud added.

That return seems improbable.

Their house was ransacked and is currently occupied by a group of armed men. “We don’t have a house anymore, no way to make a living,” Hemrin said. “If the mercenaries are still there, it is difficult for us to return,” her husband added.

“Kurds are not welcome back; the ones that go, they are killed or disappeared. The Arabs that left [NES] with us have gone back, but not us,” Hemrin explained. Human Rights Watch has documented the practice of non-state armed actors backed by Turkey of preventing the return of the displaced Kurdish families to the ‘safe zone’ they gained control of in October 2019.

The cook of Bardarash

Hamid Muhammad, a Syrian refugee from the city of Hasakah stands at his little restaurant in the Bardarash camp, 21/04/2021 (A. Medina, Syria Direct)

The little snack shop of Hamid Muhammad Said is one of the few shops that give life to the quiet camp. This 50-year-old Syrian refugee used to have a restaurant in the city of Qamishli . He, his wife and three of their children fled when the Turkish operation started.

“We were close to the borders. The bombs were falling on the houses; we were not able to sleep at night, and the kids were young, so we fled because of them,” Hamid explained.

After arriving at Bardarash, he worked for some time at a restaurant along the road to Duhok, but the transportation costs and the fact that he had to go back to the camp every 15 days to renew his work permit became insurmountable obstacles.

In February, Hamid got his residency permit, but his economic situation doesn’t allow him to leave the camp. He knows he can’t afford rent and utilities, services that are free in the camp.

Every day he goes to his shop, where he sells everything from ice cream to mashawi (grilled meat). “I am working here, but I am losing money, as the products go bad very fast because of the hot temperatures and occasional electricity cuts.”

During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the related restrictions obliged Hamid to close his shop for several months. “In six months, we didn’t leave the camp and they didn’t let us work, so we got indebted $2,000.”

He doesn’t plan to return to Syria. “If there was security, it would be better for us to be in Qamishlo, but there is no safety and I will not put my children in danger,” he said.

In Bardarash, kids ride their bikes in the wide streets and play in basketball courts. The Norwegian Refugee Council and Save the Children organization offer educational activities, and the Barzani Charity Foundation runs a Primary Health Care (PHC).

The PHC is open 24 hours a day, and all services are free, according to Marwan Idris Ali, the Psychosocial Support Team (PST) Leader. There are seven doctors, including a psychologist, a dentist and gynecologist. The PST team also offers awareness on Gender-Based Violence.

“I have big dreams”

Ibrahim Mho lives with his younger brother and grandmother in Bardarash camp, 21/04/2021 ( Syria Direct)

Ibrahim Mho walks by Hamid’s shop with his residency application in his hands. This 18-year-old on his way to do the paperwork is a ‘new arrival’. His family is from the city of Ras al-Ayn. They fled due to the Turkish operation to Bardarash but then returned to Syria.

Early this year, however, the family decided to send Ibrahim and his brother back to Bardarash again for security reasons. “The village in Syria is not good; every day, the Turkish army fires on the village, the YPG [Kurdish People’s Protection Units],” Ibrahim explained.

“I had friends here in the camp, but now all of them have left to work in restaurants. Now I live here with my grandmother and my brother, but I have no friends,” he said.

Ibrahim couldn’t enroll in high school, so he is waiting for the next academic year to register and study for the baccalaureate (high school certificate). He has accepted the idea of starting a new life in KRI but at the same time longs to emigrate to the United States or Germany.

“I have big dreams, ok? Here or in Syria, I can’t do anything with my dreams. If you go to Germany, the teaching is very good – if I get a chance, I will go,” he said in English with a confident smile.

Some resist the idea of being left behind.