Syrians at a loss after Erbil stops issuing visas

Erbil’s April 4 decision to stop issuing visas to Syrians has been a disaster for those for whom the Kurdistan Region of Iraq was a safe haven from conscription or a place to reunite with family members after years of separation.

22 April 2024

AL-HASAKAH — When Ivan Hesen received his visa to enter the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) on March 7, he was overjoyed. At last, the 31-year-old from Syria’s northeastern Qamishli city could “reunite with my wife and two children, who live in Erbil,” he said. There, perhaps they could build a better life.

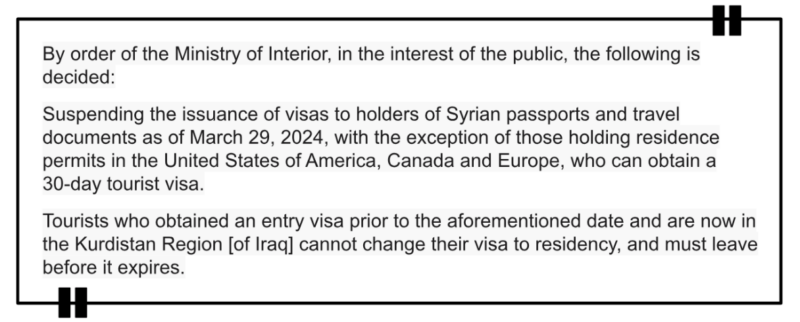

While Hesen was preparing to travel, his hopes were dashed. On April 4, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) Ministry of Interior released a decision suspending the issuing of entry visas to those with Syrian passports as of March 29, 2024. Syrians with residency in the United States, Canada or Europe were the exception, and could still obtain a 30-day tourist visa.

The text of the decision said nothing about those, like Hesen, who received their visas before it was issued but had not yet traveled to the KRI. However, many sources told Syria Direct they have not been able to enter Iraqi Kurdistan despite holding a visa and plane ticket. Without any official clarification from authorities, Syrians affected by the decision are at a loss.

The April 4 decision by Erbil’s Ministry of Interior to stop issuing entry visas to most Syrian passport holders (KRG Ministry of Interior)

One year ago, Hesen’s wife and two daughters—a seven-year-old and a two-year-old—left for Erbil via the Semalka border crossing, a river crossing that connects Syrian territories under the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) with the KRI. His wife underwent a cornea transplant in Erbil, then stayed “because of the deteriorating living situation in northeastern Syria and the continued Turkish bombing,” Hesen told Syria Direct via WhatsApp. The plan was for him to join them later.

Hesen submitted five applications to enter the KRI through the Semalka crossing, but “all of them were denied,” he said.

On March 11, Hesen tried another route, crossing illegally into Lebanon because he is wanted by the Syrian regime for mandatory military service. Once in Beirut, he obtained a passport from the Syrian embassy and a visa to fly to Erbil, then booked a plane ticket. He was supposed to arrive on April 4, the day the KRG issued its decision. At the airport, “they stopped me from getting on the plane because I am Syrian,” he said.

Syria Direct reached out several times to the Director General of Diwan at the KRG Ministry of Interior, Hemn Merany, who signed the April 4 decision, to inquire about the order and why those who received visas before it was issued are not allowed to enter. Merany did not respond by the time of publication.

On April 6, Merany told +964, an Iraqi news site, that the decision to stop issuing visas to Syrians applies to “everyone,” both single men and families. He previously stated that it was issued to “create job opportunities for the region’s youth.”

The KRG’s decision came months after the central Baghdad government stopped issuing work visas to Syrians and launched a campaign to deport those in violation of the conditions of their residency. Arab media sources have reported that the KRG’s decision came at Baghdad’s request.

Syria Direct reached out to the official spokesperson for Iraq’s Ministry of Migration and the Displaced, Ali Abbas Jahangir, for comment on the decisions related to visas for Syrians, but received no response.

The first group of Syrians deported from Iraq to northeastern Syria arrived on April 17 via the Semalka border crossing. AANES authorities stressed that the deportees would not remain in the area, but continue “to the areas from which they emigrated” in regime-held parts of Syria.

Deportations from Iraq are spreading fear among Syrian refugees in the country, particularly those who are wanted by the Assad regime. In August 2023, Syrian security services arrested four people deported from Iraq immediately upon their arrival at the Damascus International Airport.

There are more than 254,000 registered Syrian refugees in Iraqi Kurdistan as of January 2024, according to the United Nations’ Refugee Agency (UNHCR). Many asylum seekers in Erbil are awaiting resettlement in a third country.

Families kept apart

As he prepared to travel to Erbil last month, Hesen sold his furniture and borrowed money to fund his journey. So far, he has spent around $2,000 of it on smuggling costs, visa fees and a plane ticket.

“The decision has kept us apart,” Hesen said sadly. “Is this not unjust? It’s devastating.”

The father had long refused to leave Syria. “Leaving the homeland is very difficult, but when you reach the point that you can’t make a living for your children, you have no choice but to emigrate,” he said. “We can no longer live in our country, and Kurdistan, our second country, shut the door in our face!”

While neighboring countries closed border after border to Syrians in recent years, Erbil became a meeting place for Syrian families. There, many Syrians living in Europe who could not visit their country for safety reasons reunited with family members because it was easy to obtain a visa.

This month, Delshad Omar (a pseudonym) was on the verge of seeing his parents again in Erbil after nine years apart. The 36-year-old, who lives in Germany but is originally from Aleppo city, had already booked the tickets for himself, his wife and two sons, paying 2,000 euros ($2,133).

At the same time, his parents and brother obtained visas for Erbil, at a cost of $125 per person. They planned to meet there on April 25, but the new decision blocked the way. “The [travel] office canceled my family’s booking in Aleppo after the decision was issued, and told them they couldn’t travel,” Omar told Syria Direct.

“I was so eager to see my father and mother. I have two children who my parents have never met,” Omar added. He was shocked by the decision, and hopes it could be amended to allow him to see his family.

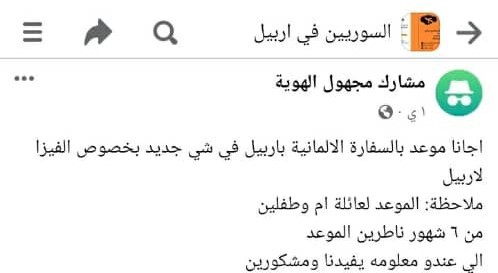

Syrians have taken to social media looking for guidance in the wake of the KRG’s April 4 decision to stop issuing visas. In one Facebook group for Syrians in Erbil, an anonymous poster asks: “We have an appointment at the German embassy in Erbil, is there anything new regarding the visa? The appointment is for a family—a mother and two children. We’ve been waiting for the appointment for six months. If anyone has information that can help us, we would be grateful.” (Facebook)

Safe haven lost

For Karim Ali (a pseudonym), Erbil’s decision to stop issuing visas to Syrians was a catastrophe. The 23-year-old, who is from Hama city, received his visa in March. He planned to settle there, “fleeing conscription and searching for a job opportunity,” he told Syria Direct via Facebook Messenger.

“There are only two months left on my deferment, and if I don’t travel by then, I will be drafted into the army and my whole future will be lost,” Ali said. He has been deliberately failing his exams “to take advantage of the academic deferment.”

Apart from the fear of conscription, life in Syria has become untenable for Ali. “I’m someone who’s done every kind of work to make a living, and all my ambitions can’t be realized because the wages I earn aren’t even enough to eat and drink,” he said.

Ali borrowed 7.5 million Syrian pounds ($506 according to the current black market exchange rate of SYP 14,800 to the dollar) to pay for his travel costs. But he, like others Syria Direct spoke to who already had visas, was not able to travel, despite the fact that Erbil’s decision does not explicitly include this group.

Erbil was one of the last doors open to Syrians fleeing compulsory military service. Without that option, they risk being drafted, putting their lives in danger if sent to the fronts. “If I don’t travel, my future is lost,” Ali said with a sigh.

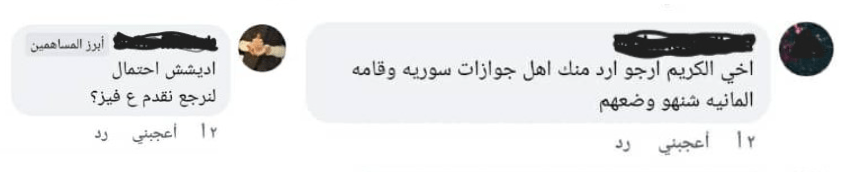

Syrians post questions about Erbil’s decision on Facebook amid a lack of clarity about who it applies to. One writes:“Dear brother, please respond. Those with Syrian passports and German residency, what’s their status?” Another asks: “How likely is it we’ll be able to apply for visas again?” (Facebook)

Faced with the shock of Erbil’s decision and a lack of clarity about who it applies to, social media and WhatsApp groups have been flooded with posts, comments and messages sent by Syrians seeking explanations of the decision, and wondering if it could be amended or canceled.

“Why give us the visa and take the fees if they won’t allow us to enter,” wondered Samer al-Ahmad (a pseudonym). The 21-year-old also received a visa before the April 4 decision, but was not allowed to enter the KRI.

Al-Ahmad, a student at Aleppo University’s Faculty of Business Administration, is on the verge of graduating. Traveling to Erbil was a way to “ensure my future” and avoid being drafted, he told Syria Direct.

Dara Bassil, a lawyer living in Erbil, expects “the KRG will amend its decision” since visa fees replenish the regional government’s coffers. Between 35 and 40 tourism companies specialized in issuing entry visas and renewing residency operate in Erbil, with each “allowed to issue 400 visas a month,” he added. Bassil works at one of those companies.

Visa fees range from $125 to $150 per person, “of which $75 goes to the Erbil government,” Bassil said. Obtaining or renewing residency costs around $400, “$350 of which goes to the regional government.”

While Bassil expects the decision could be amended or canceled, al-Ahmad is “not optimistic,” especially as Iraq starts deporting Syrians for residency violations. He has one school year left on his military service deferment, and when it ends “I don’t know where to go,” he said.

Hesen still holds on to hope. He is waiting for any new KRG statement to bring good news and see him reunited with his family. “I hope the Erbil government will reconsider the decision, which has thrown away my future.”

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.