Displaced people in Hasakah voice frustration with ‘double standard’ between informal and IS camps

Frustrated by a lack of services, residents of Hasakah’s informal displacement camps point to what they call a “double standard” from international organizations providing services at camps holding accused Islamic State members and relatives.

21 June 2023

HASAKAH — “We’re not with IS [the Islamic State], so we don’t get attention or help,” said Atta al-Wakaa, a 37-year-old father of seven living in northeastern Syria’s Serekaniye displacement camp.

He spoke about what he called a “double standard from international organizations,” accusing relief bodies of prioritizing camps holding relatives of IS fighters over informal camps in the area controlled by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES).

Al-Wakaa and his family fled Ras al-Ain, a city in northeastern Syria on the border with Turkey, during Ankara’s cross-border Operation Peace Spring in October 2019. At first, he rented a house in the provincial capital Hasakah city, but could not keep up with the monthly $50 rent (SYP 260,000 according to the exchange rate at the time). The family moved to the Serekaniye camp three years later, in October 2022.

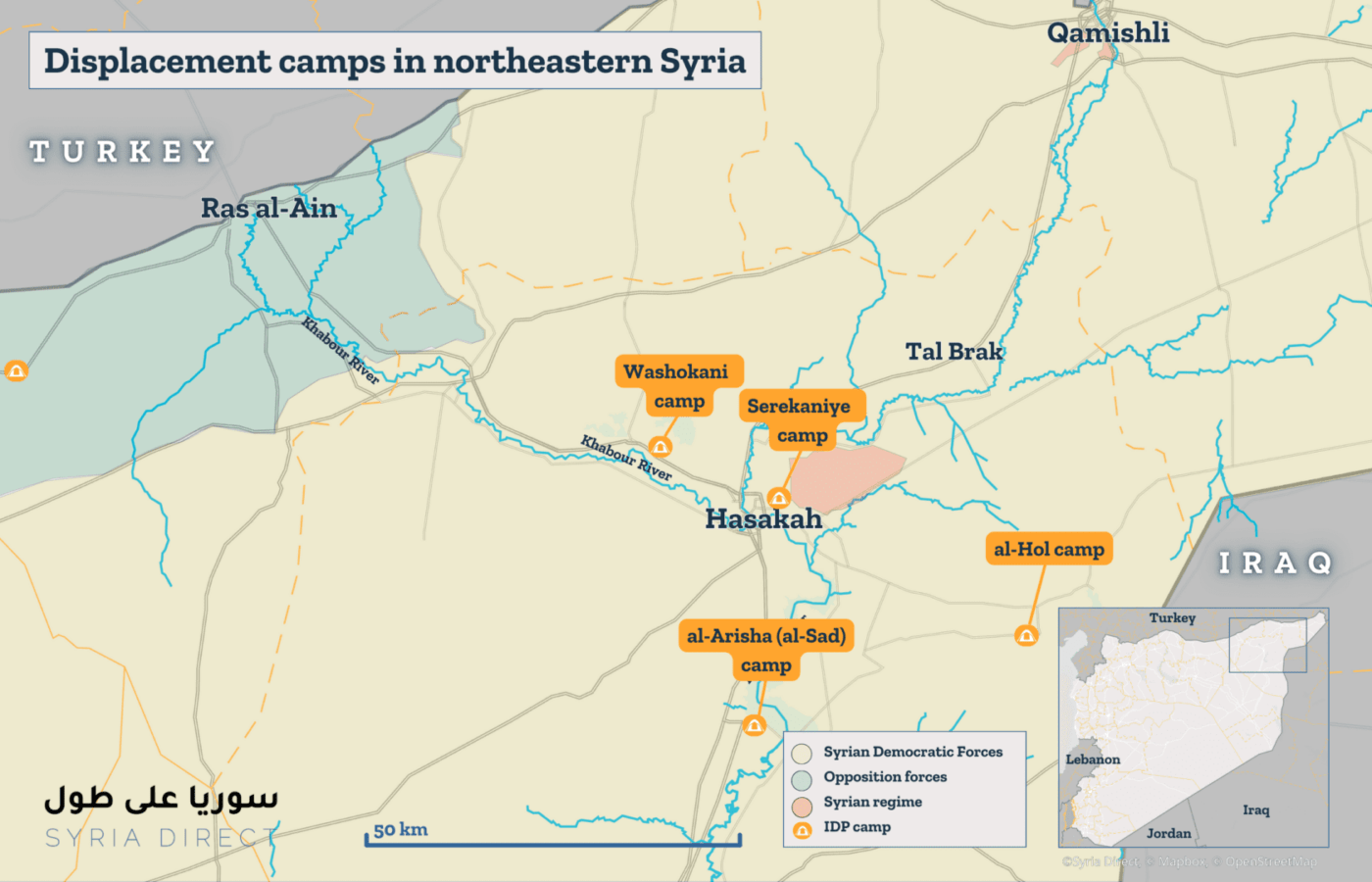

Like him, around 200,000 people were forced to flee border cities such as Ras al-Ain, Tal Abyad, Qamishli and Ain Issa during the 2019 military operation by Turkey and Ankara-backed Syrian opposition forces. Most of the displaced sought refuge in territories controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), including Hasakah province.

On October 22, 2019, 11 days after Operation Peace Spring began, Moscow and Ankara reached an agreement allowing Turkish-backed Syrian factions to take control of Ras al-Ain and Tal Abyad. But despite the operation’s end, 44,000 to 60,000 people remain displaced.

Many have settled in makeshift camps in Hasakah province and its surrounding areas, such as the Washokani and Serekaniye camps. Washokani, established by AANES during Operation Peace Spring, lies 15 kilometers west of Hasakah city and currently houses 16,562 people. Serekaniye, established in August 2020, accommodates 15,430 people, according to figures provided by an AANES source concerned with camp affairs.

Earlier, in 2016, AANES set up the al-Arisha camp, also known as the al-Sad camp, 30 kilometers south of Hasakah city. Al-Arisha, which—like Washokani and Serekaniye—is short on essential services, was intended for people from Deir e-Zor and Raqqa fleeing IS.

Displaced people told Syria Direct they feel marginalized in terms of the level of services and aid provided to the camps they live in compared to those designated for IS families. “We don’t receive the same level of care,” al-Wakaa said. “Their camps provide them with all the necessities of life, unlike ours.”

The camps al-Wakaa pointed to—namely the SDF-run al-Hol and al-Roj camps—are akin to detention centers, sites where thousands of family members or affiliates of IS have been held for years. SDF security measures aimed at preventing activity by IS cells have turned them into heavily guarded facilities, where violence among camp residents and human rights violations have been reported.

Still, residents of displacement camps look to the work of international humanitarian and medical organizations at IS camps and feel “neglected” in comparison, al-Wakaa said.

While the heavily guarded camps holding IS families and affiliates have become like prisons, the SDF’s civilian counterpart, the AANES, with support from the international community, works with international organizations to rehabilitate IS families and their children through specialized centers. Within this framework, international organizations, including the Red Cross, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the Norwegian Refugee Council and UNICEF provide humanitarian and healthcare assistance within al-Hol camp.

Deteriorating living conditions

In Washokani camp, Raghda Bulu sat stirring a pot over a fire fueled by worn clothes and refuse, as she cannot afford to buy cooking gas. “We came to the camp because we could no longer afford basic necessities or buy anything,” the 27-year-old said.

Raghda Bulu prepares lunch in front of her tent in Wokashani camp in Syria’s northeastern Hasakah province, 14/4/2023 (Honar Ibrahim/Syria Direct)

Bulu, who fled Ras al-Ain in October 2019, receives a monthly food basket that barely meets her family’s needs. But despite poor conditions, living in Washokani camp “is better than living outside it, as we don’t have to pay rent, and receive free medical care,” she told Syria Direct.

In Serekaniye, al-Wakaa teaches at a school in the camp, earning SYP 500,000 a month ($56). If he were still living outside the camp, that sum would almost entirely be consumed by rent, especially since landlords “only accept payment in dollars,” he said.

The depreciation of the Syrian pound against the US dollar and the rising cost of basic commodities make life more difficult for residents of Hasakah’s makeshift camps. They struggle to secure monthly necessities such as food, heating materials and childcare supplies like milk, which are provided free of charge to camps housing IS families, sources interviewed by Syria Direct alleged.

Due to “fear for our lives” from Ankara-backed opposition factions, Bulu cannot go back to her home in Ras al-Ain, and “moving to the cities isn’t possible because of the high cost of living and rental expenses.” For now, she has no option but to “stay here,” in Washokani. She called on international and local humanitarian organizations to enhance living conditions and provide more food and healthcare supplies.

“Do you think the organizations treat us like human beings? They treat dogs better than us. There are no services here at all. May Allah help us,” said Muhammad Khalil, a man from Deir e-Zor in al-Arisha camp who asked to remain anonymous.

Reasons behind marginalization

Sheikmous Ahmed, co-chair of the AANES Office of Displaced Person and Refugee Affairs, acknowledged a lack of humanitarian aid provided by international organizations. “The camps where families from Serekaniye and Tal Abyad live are not recognized,” he told Syria Direct.

In the absence of sufficient support from international organizations, AANES institutions and the Kurdish Red Crescent provide some humanitarian aid, healthcare and services to the camps, but their assistance falls short of meeting the residents’ needs. There are over 16 AANES-operated camps, “most of which are not recognized by the United Nations (UN),” Ahmed said.

The AANES is working “with the resources at hand to provide humanitarian aid, healthcare and camp protection, while also trying to attract more governmental and non-governmental humanitarian organizations to the region,” Ahmed added. However, “they can’t fully address the needs of the displaced in Hasakah city,” including those in Washokani, al-Arisha and Serekaniye camps near the provincial capital.

Ahmed confirmed what displaced camp residents said about a disparity in the response to ad hoc camps in Hasakah and the al-Hol camp housing IS families and affiliates. He stressed that the AANES is “actively coordinating with international organizations and the UN to address the gaps in the Hasakah camps.”

Daoud Daoud, director of the Peace and Civil Society Center (PCSC), a Hasakah-based humanitarian organization, attributed the local organizations’ inability to compensate for the lack of international support to insufficient funding. This shortfall was further exacerbated after the earthquake on February 6, as “many donors directed their resources to northwest Syria,” he added.

The life of makeshift camps’ residents in northeastern Syria “is similar to that of beggars,” said al-Wakaa. While improving living conditions in the Hasakah would bring him relief, al-Wakaa’s ultimate aspiration is to “return to our empty homes and put an end to the humiliation imposed on us by displacement and the organizations’ double standard.”

*Pseudonym used for security reasons.

This report was produced as part of Syria Direct’s MIRAS Training Program for early-career journalists in northeastern Syria. It was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Nouhaila Aguergour.