Earthquake, years of war make northwestern Syria’s buildings ‘graves above ground’

Many residential buildings in northwestern Syria were already weakened by years of bombing or built in ways that did not meet engineering and construction standards when the February 6 earthquake struck, leaving them prone to collapse.

16 February 2023

PARIS — The devastation wrought by the major earthquake that struck Turkey and Syria on February 6 has laid bare the fragile infrastructure in opposition- and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)-held northwestern Syria, the part of the country hit hardest by the disaster.

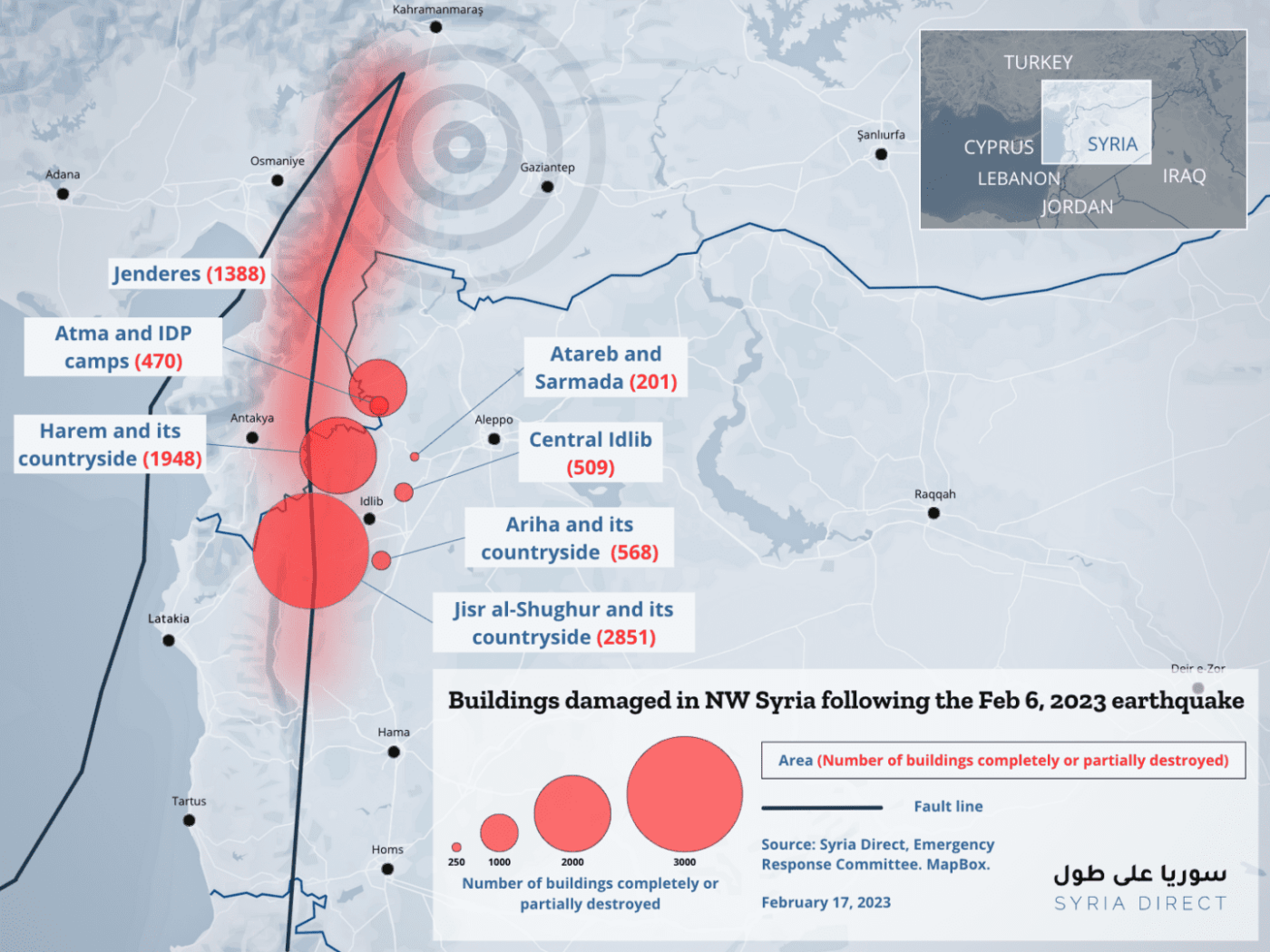

In that region alone, the earthquake killed more than 2,777 people and injured more than 12,400 others as of February 15, according to the Syrian Civil Defense (also known as the White Helmets). It also damaged and destroyed thousands of buildings, some of which were recently built.

In parts of Idlib controlled by the HTS-backed Salvation Government, the de facto authorities estimate that more than 6,547 buildings were completely or partially destroyed. And in Jenderes alone, a city controlled by the Turkish-backed opposition Syrian National Army (SNA), 1,388 buildings were reportedly completely or partially destroyed.

The human and material toll of the disaster in northwestern Syria illustrates the severity and scale of the earthquake, as well as a problem that predates it: Residential buildings in the region were not only weakened by years of bombing, but were built—by residents and humanitarian organizations alike—in ways that did not meet engineering and construction standards, leaving them prone to collapse.

Buildings completely destroyed

Hundreds of photos and videos have been shared of buildings in southern Turkey and northern Syria that were completely destroyed by the 7.7-magnitude earthquake that struck before dawn on February 6. But the strength of the earthquake, and its thousands of aftershocks, was not the only factor in the collapse of the buildings.

One compounding factor, as the head of the Association of Free Syrian Engineers, Ahmed Basem Nanaa explained to Syria Direct, was the very ground on which buildings stood. “Buildings should be designed according to the type of soil they are built on,” he said. “If the soil is not compatible with the building, tremors will be amplified. This leads to far worse problems than those faced by buildings that are suited to the soil they are built on, where the soil has been taken into account in construction.”

An equally important factor, according to Nanaa, is “the construction itself.” This depends on the engineering study for the building and the construction process: the type of building, and what kinds of materials are used. This helps explain “why some buildings collapse completely while others are partially damaged or escape damage.”

And notably, “buildings that have experienced hundreds of tremors due to aerial bombardment, thermobaric and sonic missiles, artillery shelling and the use of other destructive weapons by the Assad regime over the past decade are at higher risk of additional and accelerated damage,” Nanaa added.

Structural engineer Muhanad al-Jahmani, who lives in the northern Aleppo countryside city of al-Bab, also stressed that years of war and damages from bombardment by pro-regime and Russian forces weakened many residential buildings in northwestern Syria.

Additionally, “residents restored damaged homes themselves in past years, without specialists or any engineering inspection of the state of the building and the cracks in it,” he said. Instead, they merely “repaired the bricks or cement coating, concealing only the visible defects.”

Consulting engineer Akram Tomeh, who is also the former vice president of the opposition Syrian Interim Government (SIG), told Syria Direct that “missile attacks and bombardment by the regime and Russia significantly damaged residential buildings.” Meanwhile, “widespread poverty among those affected by bombardment prevented them from restoring, reinforcing and conducting assessments on their homes.” When the earthquake came, it “demonstrated the extent of the disaster affecting residential buildings,” he added.

In addition to the buildings damaged by bombing in northwestern Syria, which is home to more than four million people, half of whom are displaced, many buildings “do not meet construction standards due to structural design, the use of non-resistant concrete, and iron bars with the wrong diameter, or that are incorrectly spaced,” al-Jahmani said.

The February 6 earthquake was destructive “due to how long the tremors lasted and how strong they were,” al-Jahmani said. But while “structurally sound buildings would still be affected by the strength of the earthquake,” issues related to building quality and resilience are key.

Syria Direct contacted the local councils in the cities of Azaz and Jenderes to ask if they had reports on the state of residential buildings prior to the earthquake, but received no response by the time of publication.

A media source from a local council in the northern Aleppo countryside, who asked to remain anonymous, told Syria Direct that all opposition-affiliated local councils “failed to conduct field surveys of buildings in the areas they are responsible for and do not have any previous reports on the state of the buildings.” This was also confirmed by Tomeh.

Jenderes, in the Afrin district of Aleppo province, was hit hardest by the earthquake in Syria. As of February 12, the city’s death toll from the earthquake was 1,012, with 1,110 buildings partially damaged and 278 completely destroyed. Second in terms of the number of destroyed buildings was Atma, where, as of February 13, 223 buildings were partially damaged and 30 were completely destroyed, leading to 38 deaths, according to the HTS-backed Salvation Government’s Emergency Response Committee. Third was the village of Besenya, in the Harem district of Idlib’s countryside, with 11 partially damaged and 24 completely destroyed buildings, resulting in the death of 200 people.

Dozens of residents gather on top of the rubble of completely destroyed residential buildings in the village of Besenya, situated in Harem District in northern Idlib province, 02/09/2023 (Abd Almajed Alkarh/Syria Direct)

The location of these three Syrian areas explains why they were so badly affected. Although the epicenter of the first earthquake that struck on February 6 was near the Turkish city of Kahramanmaraş, it was felt just as strongly as far as the city of Antakya, some 180 kilometers to the south, said Nanaa, from the Association of Free Syrian Engineers. “If we draw a line between these two cities, the areas of damage become clear,” he said.

“There were [seismic] waves of equal intensity—the intensity of the shaking in Antakya and its surroundings was just as strong as in Kahramanmaraş and its surroundings,” Nanaa said.

The line between the two cities and the surrounding area “is a fault line that generates violent earthquakes,” he added. Because “Jenderes, Atma, and Besenya are close to the city of Antakya, which is in the Turkish state of Hatay, they were the most affected.” Jenderes lies 68 km east of Antaka and 180 km south of Kahramanmaraş.

‘Graves above ground’

In the early hours of February 6, Abu Malik, his wife and three children rushed out into the street after feeling the tremors at their home in Idlib city. None of them were harmed. Hours later he received news of “the tragedy”: All of his relatives living in Besenya, in the northern Idlib countryside, were under the rubble of their collapsed homes.

After several days of search and rubble removal efforts, he received the heartbreaking news that 26 of his relatives had died, although one 14-year-old child survived.

Abu Malik’s relatives had been renting several apartments in a private housing project that collapsed in the earthquake, he told Syria Direct. The al-Batal Housing Project was made up of 30 residential buildings, each consisting of four floors, and all were leveled by the earthquake.

Abu Malik partly blamed the owner of the project. “The project buildings were not properly supported with cement and iron, and poor quality bricks were used,” he said. He described the housing units as “graves above ground.”

The day after the earthquake, HTS leader Abu Muhammad al-Jolani visited the village of Besnaya, which is under HTS control, and promised the bereaved families of the housing project’s inhabitants that those responsible would be held accountable. Subsequently, Abu Malik said, “we learned that the owner of the housing project was arrested.”

Nanaa, of the Association of Free Syrian Engineers, said that neither the body he heads nor the local councils have “a monitoring mechanism to ensure that the implementing parties, people or organizations working on shelter projects for displaced people comply with the engineering standards set out in construction codes.”

He attributed this to “the weakness of local councils and the lack of centralization, or of any executive authority that can implement decisions and apply standards.” His association has been sidelined, he said, “under the pretext that it has a political stance, despite the Association of Free Engineers being an independent technical body.”

The lack of oversight of construction projects by individuals or humanitarian organizations meant “some housing complexes fell at the very first tremor,” structural engineer al-Jamhani said. “Residents did not have time to evacuate the building—as inhabitants of other buildings did—before it was destroyed, which indicates an immediate collapse, and that some buildings did not meet engineering regulations and codes.”

Al-Jahmani explained that a significant portion of current construction projects in northwestern Syria are located on agricultural land, without stone foundations. These buildings “have no stability, and any earthquake will cause a fracture or collapse in the neck columns, which means residents on the first and second floors won’t be able to escape if it collapses.”

New homes on the verge of collapse

Two months ago, Abu Muhammad, a Palestinian-Syrian displaced from the Yarmouk camp in Damascus, moved with his family from one of the displacement camps on the Syrian-Turkish border to the village of Haifa al-Karmal, in the northern Idlib countryside. The village is made up of around 800 apartments of varying sizes that were built using donations sent from Palestine in order to move displaced people from tents to concrete houses. Two residents of the village told Syria Direct that the construction was overseen by the HTS-affiliated Salvation Government.

Abu Muhammad said that, with the exception of a partially collapsed ceiling in one apartment, the village did not experience significant damage as a result of the recent earthquake, although cracks developed in the walls and floors of some apartments. This was confirmed by another Palestinian-Syrian resident, Abu Suleiman.

While the buildings suffered less earthquake damage than other areas, both men told Syria Direct they have faced other problems: “severe issues with damp, water leaks and rainwater collecting close to the buildings.”

Still, the earthquake left Abu Muhammad and Abu Suleiman fearing that apartments would collapse over residents’ heads, especially as the two-floor units were built without a foundation or columns, with load-bearing walls. This type of building poses major problems in disasters “as it is not resistant to earthquakes and cannot withstand the accumulation of rainwater in its surroundings,” engineer al-Jahmani said.

“The blood of Syrians is worth more than that. We do not want housing in the place of tents if Syrians are killed inside it,” he added.

Before the disaster, the Association of Free Engineers presented “many plans, especially after the organizations got involved in building and construction,” Nanaa said. “There are many comments and questions about why the issue of earthquakes was not taken into account when the buildings were constructed.”

He said the body had sent official letters to the SIG, local councils and some humanitarian organizations, particularly in relation to public buildings, calling for the dossier for any building to include an “earthquake dossier.” But “most of the buildings constructed by organizations have not taken any earthquake-related requirements into account,” he said, citing “donor and aid policy.”

The rubble clearing process and search for survivors in the village of Besayna, in the Harem district of northern Idlib province, 02/09/2023 (Abd Almajed Alkarh/Syria Direct)

A dark future

“It is not possible to say that the earthquake is over as we may yet witness aftershocks in the short or long term,” al-Jahmani said. The responsible authorities must therefore “conduct an engineering assessment, and there should be a specialized engineering team in each neighborhood,” tasked with “preparing a report in collaboration with local councils and the Association of Engineers that assesses the engineering of every building, especially in areas that have experienced significant damage and cracks,” he added.

“There are cracked, uninhabitable buildings that need to be removed while others need to be reinforced,” the engineer emphasized. He feared the “possibility of buildings collapsing as a result of further aftershocks.”

In the aftermath of the earthquake, the Association of Free Syrian Engineers launched an online form allowing residents to provide information about their building and attach photos of damage and cracks in the building, in order for an engineering assessment to be carried out. As of February 14, a total of 2,700 submissions had been received.

Nanaa said the Association’s Aleppo branch also formed “teams of engineers to assess the state of buildings following the earthquake, starting from Azaz, then Afrin and Jenderes.”

The assessments categorize buildings according to three grades: An “S” rating means the building is sound and usable, while a “D” rating means it is damaged and must be evacuated until it has been reinforced and repaired. And a “DD” rating means the building has collapsed, must be removed and should never be used.

Muhammad Haj Abdo, a lawyer and member of the Afrin City Council’s Emergency Committee, told Syria Direct that “the assessment of damage in the city is ongoing,” but the council “has been able to inspect 1,203 of the city’s most affected houses out of the 32,000 apartments and detached houses in the city.”

The damage assessment in Afrin revealed that three buildings collapsed and 500 homes were uninhabitable unless reinforced or rebuilt, while 700 were left partially damaged, Haj Abdo said.

As assessments continue, “the Association of Engineers’ final report on the state of buildings after the earthquake may conclude that there is significant damage to buildings that will therefore require reinforcement or removal,” Tomeh said. But “it is difficult to force the owner of a building to reinforce or remove it, due to the economic conditions in the region.”

This report was originally published in Arabic.