For Idlib’s women artists, art the ‘gentlest and most powerful’ tool

Women artists are creating and innovating in northwestern Syria, using art as a universal language to convey messages to the world and tackle issues their communities face.

31 October 2023

IDLIB — “I seek out any blank or dull surface that I can bring alive with colors,” Yafa Diab said. Through peace and war, the 25-year-old painter’s passion for art has been a lifelong love story.

Growing up in Binnish, a city in Syria’s northwestern Idlib province, Diab painted beauty: roses, birds, nature. When the Syrian revolution broke out in March 2011, her artistic journey took a different turn.

She did not put down her brush, but turned it into “a way to support the people of my country, and their demands,” Diab told Syria Direct. Her paintings capture Syrians’ concerns and the circumstances they are living through. She is best known for her “Eye of the Revolution” oil painting, for which she won the International Peace Prize at Art Without Borders for Peace and Defense of Human Rights, an international exhibition held in Italy in 2022.

“Eye of the Revolution,” an award-winning oil painting by Yara Diab, an Idlib-based Syrian artist (Yara Diab)

“My inspiration stems from my homeland’s causes, the war, detainees’ stories, positive and negative emotions, beauty and even inanimate objects that stir new feelings within me,” Diab said. Alongside her paintings, she draws, sculpts and creates handicrafts.

Women artists in northwestern Syria, like Diab, continue to create while facing the same challenging security and economic conditions that impact more than six million people in the opposition-held area, including around two million people in displacement camps.

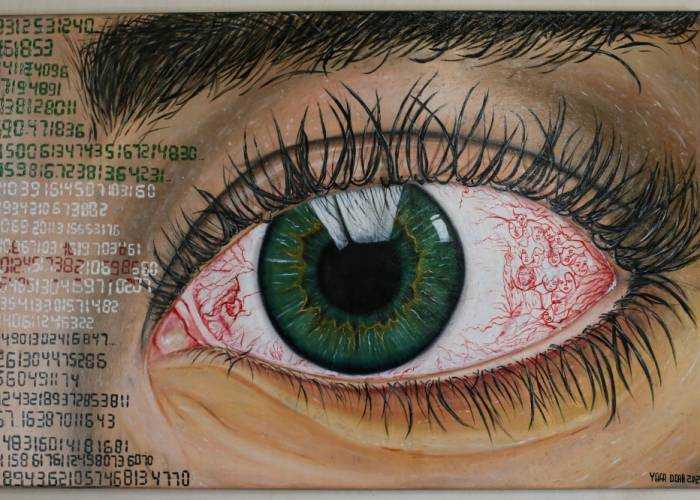

Amany al-Ali, a 38-year-old Idlib city resident, began her artistic journey in 2016, creating social and political caricatures. She is the first female cartoonist in Idlib, and her work has been published in several local, regional and international websites. “I initially worked with Souriatna newspaper, then the New Arab [website] and later Horrya Press,” al-Ali told Syria Direct. “I also worked with foreign websites, and am currently working with a French newspaper while also collaborating with Arab newspapers.”

Earlier this month, “Behind the Lines,” a documentary about al-Ali directed by Alisar Hasan and Alaa Amer, won the Horizons Award at the French Grand Bivouac film festival. The film was part of the six-part “Draw for Change” series awarded Best Documentary Series at the 2023 Cannes film festival.

A caricature by Amany al-Ali, created shortly after the devastating February 6 earthquake in northern Syria and southern Turkey, depicts the mutual aid and support residents of affected opposition-held areas provided to each other, 10/2/2023 (Amany al-Ali)

Art as a powerful weapon

Throughout the Syrian revolution, art has emerged as a global language for Syrian artists to convey messages to the world and express solidarity.

“I used graffiti to communicate directly with the world and draw attention to our cause, without barriers or restrictions,” painter Salam al-Hamedh, 32, from the western Idlib city of Jisr al-Shughour, said. “Art has a strong capacity to convey powerful messages to the world.”

Al-Hamedh had a talent for drawing since she was a child, but she realized the power of art during the Syrian revolution. The brush “became a weapon and a tool I used to express my emotions,” she told Syria Direct.

“With my brush, I depict the suffering of the oppressed, the struggles of the displaced and scenes of injustice and oppression,” al-Hamedh added. “This includes bombings, detainee voices, global inaction and the absence of humanity.”

Like al-Hamedh, al-Ali uses her caricatures to send a message, as it “best resonates with my personality and preferences,” she said. Through this satirical art form, she can “get the idea across in a funny, sarcastic and intelligent way, ensuring that my message is universally understood across different languages without the need for an explanatory text.”

Since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, new forms of artistic expression have emerged in Syria. One example is Akram Suwaidan’s “Painting on Death” project. Suwaidan, displaced from the East Ghouta suburbs of Damascus to northwestern Syria in 2018, transforms shells and war remnants into art pieces. Similarly, muralist Aziz al-Asmar uses bombed-out buildings in Idlib as his studio.

A work by Syrian artist Akram Suweidan in solidarity with cancer patients in northwestern Syria as part of his “Painting on Death” project, 24/7/2023 (Painting on Death)

Social and financial hurdles

While successful women artists have emerged in northwestern Syria, they face a number of obstacles, including criticism from the local community and marginalization by local organizations, a number of artists told Syria Direct.

Sometimes, these challenges start much closer to home, with family being the initial obstacle for women interested in art. But if they are able to overcome it, women can confront society’s discouraging voices from a position of strength. Al-Ali’s family initially opposed her involvement in art, “but later allowed me the freedom to choose my path, and they now express support and pride in my art and achievements,” she said.

While al-Ali has faced occasional criticism from her community, she notes a positive change over time. She now feels that “people around me, especially men, have become more accepting and welcoming, particularly since I’ve established myself as a cartoonist whose work has reached Europe.”

But some criticism persists, especially when al-Ali addresses issues related to violence against women, and is “accused of distorting men’s image,” she said. In reality, “such issues are prevalent in the area, especially within refugee camps,” she added. “My goal is to expose what’s happening. If we don’t want to see it, then let’s put an end to it.”

One of the limitations on women’s artistic freedom is the lack of support from local community organizations for their work, and the need to buy their own art supplies as a result. “I haven’t found any [financial] support at home, whereas abroad they are racing to support me and organize exhibitions of my work,” al-Ali said. “Soon, my work will be displayed in Belgium and France.”

In Idlib, al-Ali participated in a single event four years ago. In Europe, not a month goes by without one of her pieces being displayed or an exhibition being organized for her.

The caricaturist emphasized the importance of supporting artists, noting that “drawing doesn’t generate enough income for men and women artists at home.” For a woman artist to sustain her talent and passion, she “needs to secure another job to fund her art,” she said. While al-Ali loves drawing caricatures, “it doesn’t bring in enough income on its own, so I supplement my earnings by working with wax [sculptures] and collaborating with foreign newspapers so I can keep making art.”

There have been some initiatives in northwestern Syria to support women’s art, including a vocational apprenticeship offered by the Syrian Rural Women’s Association. This project—which began in July and runs through the end of November—provides mosaic art training to 15 women in Idlib’s Ariha city, both residents and displaced people, Safa Lattouf, the association’s director, told Syria Direct.

In addition to a one-month training, beneficiaries are provided with the materials and equipment to create a home artwork, under the supervision of a member of the association’s staff, Lattouf explained.

The association chose this art form because it helps support and stabilize society and offers job opportunities for women trainees, Lattouf said, adding that the association seeks to turn art into a source of income. “Trainees can set up a small workshop in their homes to create mosaic panels for sale, each priced between $30 and $150.”

Women take part in the Syrian Rural Women’s Association’s mosaic vocational apprenticeship project in Idlib’s Ariha city, 11/9/2023 (Obaida Daaboul)

“I can now work and make high-quality mosaic artworks,” Umm Muhammad, 30, one of the vocational apprenticeship’s beneficiaries, told Syria Direct, expressing satisfaction with the training. However, “it’s difficult to find a job or manage production,” she added. Bisan Faour, 34, another beneficiary of the same project, shared the same sentiment.

Painter Diab emphasized that “organizations have a major role to play in supporting artists’ careers, but they haven’t provided this support.” She called for organizations to “visit artists, understand their living conditions, and provide an environment that is psychologically and physically suitable, as well as financial support—including materials to help them create.”

Feminist revolution

One of the challenges women artists in Idlib face is “the general perception of art in its various forms as mere entertainment,” which “limits the use of art to serve and support society,” Lattouf said.

“Idlib’s women artists face many challenges,” feminist writer and researcher Alia Ahmad told Syria Direct, “Idlib’s women artists face many challenges, starting with the siege imposed on the city and the death surrounding it on all sides. Their problem does not end with battling stereotypes that confine them to conventional roles, underestimate their capabilities and fail to offer them the necessary support.”

But despite all the obstacles, the contributions of women artists in Idlib have come to the forefront, “and their impact extends beyond their artistic and creative value, representing a form of feminist revolution, even if they don’t define it as such,” Ahmad said. She believes “they can convey messages of peace to the world that reflect the beauty, richness and diversity of Idlib and the splendor of Syria, despite all the violence we’re drowning in. But women artists need real and well-organized support to achieve this.”

“Through their art, women offer new creative ways to address deeply human issues from an inherent feminist perspective, reflecting self-love among women,” Ahmad added. Expressing themselves and confronting violence through art “is both the gentlest and most powerful approach. These rich contributions show tremendous courage, and deserve more support from everyone.”

Diab, the painter in Binnish, hopes to see “a collective office or studio space to bring women artists together, increasing their activity and fostering positive coordination between them.” She also dreams of “exhibitions created for their works, marketing their artistic production.”

For now, she continues to fund her own work. “Art hasn’t provided economic stability for me yet,” she said.

**

This report was produced as part of the second phase of Syria Direct’s MIRAS Training Program, in coordination with the Syrian Rural Women’s Association. It was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Nouhaila Aguergour.