‘For sale due to travel’: Syrians sell homes, land and cars to cover migration costs

In SDF-held northeastern Syria, residents are selling and mortgaging their land and houses as a last resort to finance costly, and potentially deadly, journeys to Europe.

15 September 2022

AMMAN — Even after weeks of risk and extortion, Delshad Darwish (a pseudonym) is adamant that “the danger of migration is better than starving to death or waiting for an unknown future.” Today, he is in Serbia, a temporary stop where he waits to gather enough money to continue on to his final destination: Germany.

In July, Darwish, 36, decided to leave his hometown, Amuda city in Syria’s northeastern Hasakah province. He left his wife and two children behind, hoping to start family reunification procedures after arriving in Germany and obtaining asylum. Because he could not afford smuggling costs to reach Europe, he chose to sell his 2.5 dunams of land (0.25 hectares) for $10,000.

A smuggler agreed to take Darwish from Amuda—which is in an area controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—to Istanbul by way of Ras al-Ain, a town on the Turkish border controlled by the Ankara-backed Syrian National Army (SNA), for $3,000. But during the journey, Darwish “fell into the hands of the Ahrar al-Sharqiya faction, after the smuggler handed me over to them,” he said. The SNA-affiliated faction demanded “an $8,000 ransom to release me and ensure I arrived in Istanbul.” His family “gave in to their demands, and transferred the money.”

Before setting foot outside Syria, Darwish had spent more than the price of his land, and was still at the beginning of his asylum journey.

In Syria, there is a common saying that “land is like honor,” something that cannot be abandoned no matter how bad things get. But since the beginning of 2022, the practice of selling or mortgaging land, real estate and cars has started to spread among residents of SDF-held northern Syria looking to pay the high costs for a way out, several sources told Syria Direct.

Many Syrians are convinced that their country is no longer a livable place, including the SDF-controlled areas with an estimated three million inhabitants. The decision to sell their property is the last card they have left to play, as Syria’s economy continues to deteriorate. The Syria Economic Monitor, a semi-annual publication of the World Bank, predicts that Syria’s real GDP will contract by 2.6 percent in 2022, after it fell 2.1 percent in 2021. Conflict, displacement and a collapsing economy are lowering living standards for Syrian families across the country.

The last card

There are no official or approximate figures of the number of people migrating out of northeastern Syria. But reaching Europe is the talk of young people today in northeastern Syria, a region where economic and security conditions are deteriorating. The area’s residents also fear a Turkish military operation, a threat Ankara brandishes from time to time.

Approximately 90 percent of Syria’s population lives below the poverty line. And out of 18 million people, 14.6 million need humanitarian assistance, according to a May 2022 report by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). “The extensive destruction and gradual deterioration of vital infrastructure—water, electricity and health care—are stretching the population’s ability to cope,” the report said.

As people look for a way out, both SDF and SNA forces—the two dominant parties in control of northern Syria—are involved in the “business” of smuggling people to Turkey, according to recent media reports.

People from SDF areas leaving Syria cross through “the Ain Diwar border area belonging to al-Malikiyah city [which links SDF areas with Turkey] or [SNA-controlled] Ras al-Ain,” said activist Hussam al-Qass, who lives in the northeastern Hasakah province city of al-Malikiyah (Derik)

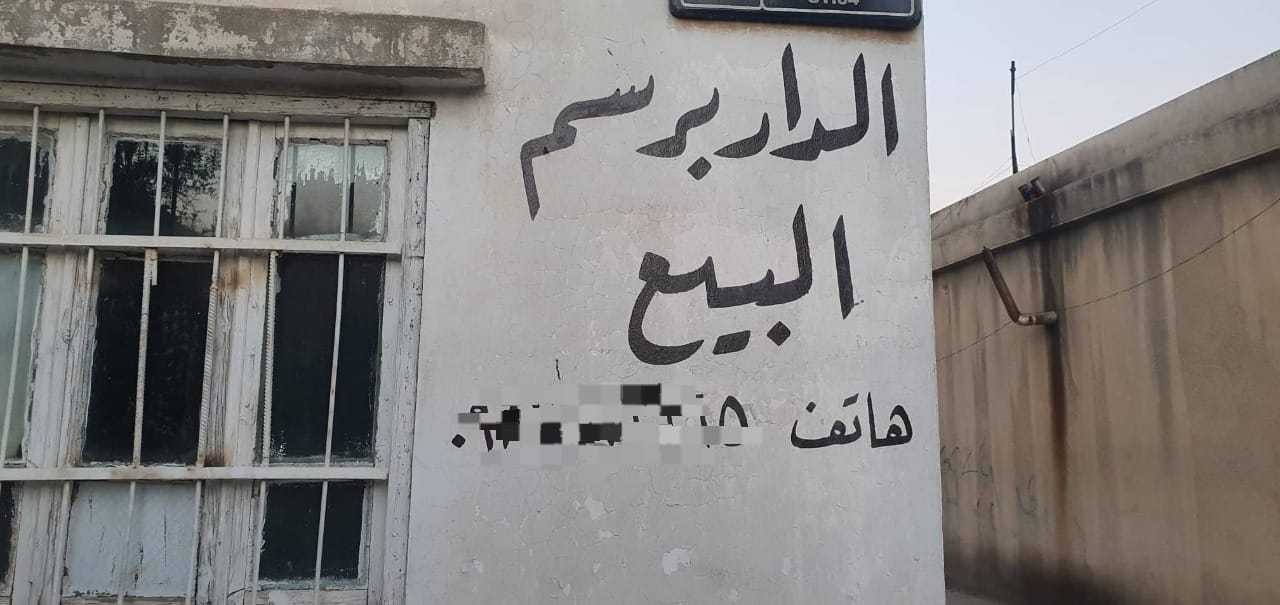

Al-Qass has noticed an increase in the number of people migrating from his area, especially young people. Walking about al-Malikiyah, one finds “offers to sell real estate, land and cars due to travel, that is, to provide money for migration,” he said.

Selling property and cars to emigrate is the last resort for young people to finance their travel. But the youth who are leaving in increasing numbers were themselves the last resort for the local community, “the pillar of the local economy and the productive category,” al-Qass said.

Despite its dangers, for young people migration is the only way out of “a financial situation that is going from bad to worse,” said Alaa Raouf (a pseudonym). Raouf lives in SDF-controlled Manbij city, and earns $3 a day working at a vegetable market. Daily expenses for his family of four come to “more than $10,” he told Syria Direct. He, too, is looking for a way to finance a journey out of Syria.

A risky route

Without solutions for resettlement or regular migration to European Union (EU) countries, Britain and America, Syrians leaving recently are turning to irregular migration. Doing so, they risk their lives and their money, as in the case of Darwish, now stuck in Serbia.

After the ransom was paid to Ahrar al-Sharqiya, Darwish was released and reached Istanbul. A smuggler there agreed to take him to Serbia via Greece for $2,000. He made it there, but was surprised by how difficult it was to continue on to Germany. A smuggler in Serbia offered to take him for $5,000, but because the money from selling his land went to pay his ransom, Darwish’s wife sold her gold jewelry “to finance the rest of my trip,” he said, but it was not enough to cover the full cost.

Darwish has lost all the money meant to buy his way to a new life on a journey that is not over yet. He risked his life, like a number of other Syrians who have died trying to reach Europe, or after reaching its shores. This week, six people—three children and three women—from Syria’s eastern Deir e-Zor province died of thirst, starvation and burns after their boat was lost in the Mediterranean Sea for a week. In August, a young man from Deir e-Zor died in the forests of Greece after he fell ill during his journey and was buried there.

Added to these risks, some Kurdish migrants from northeastern Syria—especially former employees of the Autonomous Administration in North and East Syria (AANES) or one of its affiliates—are apprehensive about crossing to Europe through Turkish territory for fear they could be wanted by Turkish security services. Akeed Bouzan (a pseudonym), who previously worked for the AANES in Hasakah province, is one of them.

This year, Bouzan, 25, decided to leave Syria through Damascus, by getting a student visa from Belarus. Because he, like others, did not have the money for the trip, as his monthly income was less than $70, his brother mortgaged his farmland to cover the costs.

Bouzan reached Damascus after making arrangements with “comrades in the Coordination Office” in Qamishli, which coordinates between the AANES and the Damascus government. He applied for the visa, on condition he pay $3,200 total for it and a plane ticket, he said.

If the visa is approved, Bouzan plans to travel to Belarus and then consider making his way to Germany, where one of his brothers lives. Doing that would require “agreeing with a smuggler to take me from Belarus to Poland, and on to Germany,” a trip he expects to cost between $2,000 and $5,000.

While he is aware of the risks involved in his plan, “life in Syria has become impossible,” Bouzan said. “Daily Turkish threats [of a military operation against SDF-held northern Syria] have stopped our lives, and cast us into the unknown.”

A house for sale in al-Malikiyah (Derik), northeastern Syria, 13/9/2022 (Syria Direct)

A search for funding

The dangers of smuggling routes to Europe have long prevented some Syrians from making their way by rubber boats and through forests, but facing what seems like a dead end in Syria, many people are thinking not of the risks, but rather how to pay for the chance to take them.

Alongside selling or mortgaging property, as in the case of Darwish and Bouzan, some have found other ways to pay. One method is to buy a car in installments and sell it for cash used to fund travel, which is what Raouf, in Manbij, is thinking of doing. “People in Manbij have done that since the refugee wave began,” he said.

Raouf expects his journey to Europe to cost $9,000 or $10,000: from his SDF-held city, through SNA-held Jarablus and Azaz, on to Istanbul, and from there to Greece, Austria or Serbia, and finally Germany.

At best, he can cover “more than half the cost by buying a car worth $10,000 in installments and selling it for $5,000 in cash,” he said. But that leaves the rest of the money, which is what currently stands between him and leaving.

Muhammad al-Said, a car dealer in Manbij, said “the people of Manbij don’t usually part with their land and houses, but look for alternatives like a mortgage and buying a car in installments to sell for cash, provided they can make the monthly payments.” But some people have “broken with local custom and sold their house and land to finance a journey,” he added.

If a buyer cannot purchase a car outright, land or a house is mortgaged as collateral, provided it is canceled after installments to the car office or dealer the vehicle was bought from is paid, al-Said said. He warned that the risks of the route, and the possibility of people arriving late to their destination in Europe, or not being able to meet the terms of the agreement, “could lead to losing the mortgaged property, as stipulated by the contract.”

There are three stages to the process of selling a car to travel, al-Said said: The person wishing to emigrate buys a car in installments, providing payment guarantees such as collateral property or a guarantor, then sells the car back to a dealer for half the price in cash. “In turn, we offer it for sale with a profit margin,” he said. This process has “become a phenomenon in the region since the start of the year,” al-Said added. “I alone bought and sold more than 50 cars this way, and there are other traders, too.”

The car market in Manbij was initially boosted by car sales, al-Said said, recalling the popular saying that “one person’s loss is another’s gain.” But the market returned to a standstill after “supply became greater than demand,” he added.

Raouf is aware of the risk involved in the methods used to find funding for travel in Manbij. But his hope lies with a future that, “regardless of the outcome, is better than the situation I’m living in.” Darwish agrees. From Serbia, he still hopes to make it to Germany to start the process of reuniting with his wife and children. They are waiting for him in Amuda.

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.