Giving up amidst rising pressure: Portrayals of Syrian despair in Lebanon

On average, every three days a person in Lebanon takes their own life, while every six hours someone attempts to complete suicide.

14 February 2021

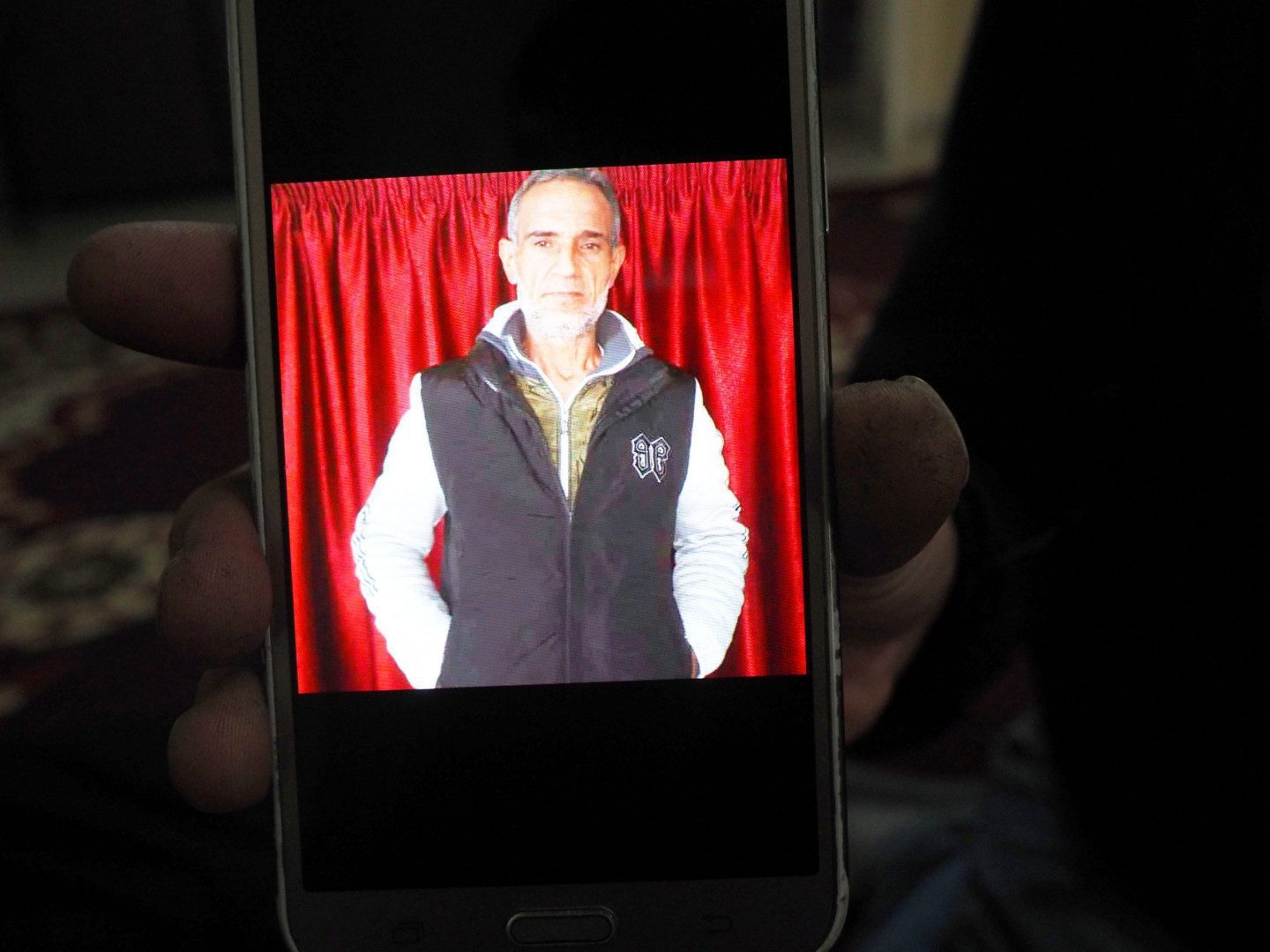

Haitham shows a picture from his phone of his late father Bassam al-Halaq, 04/02/2021 (Syria Direct)

TAALABAYA — At dawn on April 5, 2020, Bassam al-Halaq, a father of two and grandfather of four, left his house in Taalabaya in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley and set himself on fire.

On average, every three days a person in Lebanon takes their own life, while every six hours someone attempts to complete suicide, according to Shireen Makarem, a Communication Manager at Embrace, the first suicide prevention hotline in Lebanon.

Bassam used to earn his living as a construction worker in Daraya, in the countryside of Damascus. But since the 51-year-old fled the Syrian war and arrived in Lebanon five years ago to join his wife and two sons – who had arrived in the Beqaa Valley in 2014 – work had been scant.

The al-Halaq family belongs to the UN statistic warning that 90% of Syrian refugee families live in extreme poverty – with 308,728 Lebanese pounds (LBP) per person per month (approximately $34 at the current black market rate) – and are in debt. In the case of the al-Halaq family, they said they owed $2,000.

Huddling around an oil stove warming their bare living room, Bassam’s widow, Sanaa al-Qarh, and her two sons, Haitham and Abdulrahman, agreed on the reason Bassam gave up: too much pressure.

“The living conditions are hard; he was the one responsible for providing for the family,” Abdulrahman said. “It was too much psychological pressure,” Haitham added. Both brothers have been working in construction, but the work stopped in 2020. “Everything got worse,” Haitham said. “He was under a lot of pressure; he could not bear it,” agreed Sanaa.

Bassam had not mentioned suicidal thoughts before. “Days before he died, he had very sweet words. He was joking, we were laughing, having a good time,” Sanaa recalled. “Two days before he took his life, I did not notice anything different in his behavior. He was kissing my kids; we had dinner,” Haitham said. “He had a great heart,” Sanaa added with a sad smile.

Twenty-seven-year-old Haitham has three children, while twenty-five-year-old Abdulrahman has one. Together with their wives they live under the same roof as their parents. On the day of Bassam’s suicide, they were all asleep when a cousin called them at 7 am to inform them of Bassam’s fate.

An ambulance took Bassam to the Bekaa Hospital, where he received first aid. But the family was asked for two million LBP to transfer him to another hospital to get his severe burns treated. “We don’t have money for food; how are we going to have two million?” Sanaa exclaimed.

The family was unable to gather that amount. At 5 pm, the doctors informed them Bassam had succumbed to his wounds. “In the hospital, they were not human, they just cared for money,” Haitham angrily said.

The Halaq family is registered with UNHCR, and as with 69% of Syrian households in Lebanon, they don’t have legal residency. During their six years in Lebanon, they said they have only received UNHCR cash assistance for three months.

Before Bassem’s suicide, he and Sanaa went to UNHCR Zahle Office. “We told them we don’t have enough for bread, for food, for the rent. But they told us we did not qualify to receive help,” Sanaa explained.

Since October 2019, food prices have increased 174% while the depreciation of the Lebanese currency – trading now at 8,500 per dollar in the parallel market while the official exchange rate is 1,500 – has evaporated the middle class and condemned lower-income families to destitution.

After Bassam’s death, the family said they have not received any cash assistance from UNHCR or local associations. Their relatives have stepped in, and sometimes the two brothers work at a shawarma restaurant run by their cousin.

In over a year, Lebanon has witnessed a social uprising, an economic collapse, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Beirut explosion. These events have placed “a burden” on many who cannot cope anymore. In this period, calls to the Embrace suicide prevention hotline have increased “significantly,” said Makarem.

“I am upset, I am psychologically tired, our nerves are collapsing, but I cannot do anything,” Haitham said. When asked if they had received any kind of therapy, the brothers rolled their eyes. “No therapy. Our faith is strong,” Haitham responded.

“We came here escaping war, we lost everything, we lost our house; from bad we went to worse, we find no rest,” said Sanaa. The brothers said they cannot return to Syria for fear of being conscripted into the military. “We don’t know about our future; we live day by day,” Haitham said. Their debt today stands at $1,400.

“This is how our exile has ended up,” Sanaa concluded.

The threat came true

Eight months after the al-Halaq family lost Bassam to suicide, the story repeated itself. Syrian refugee Majed Khalil al-Musa set himself ablaze in front of UNHCR Beirut offices on November 5, 2020.

Majed’s family declined to talk to Syria Direct, but Khaled al-Yousef, spokesperson of the participants of the sit-ins to demand their rights as refugees that took place in front of the UNHCR office in Beirut during last year, shared details about Majed’s case.

Majed’s 13-year-old daughter suffered a malignant tumor in her chest and legs. For months, the Syrian family struggled to get UNHCR to cover the expensive operation ($54,000), according to al-Yousef. Eventually, it was decided the girl would undergo surgery at the American University of Beirut Medical Center. On the day of the intervention, the family was informed that UNHCR could not cover the operation’s cost.

Majed instantly rushed to UNHCR’s offices and threatened to set himself on fire if they did not cover the operation.

A few hours later, he did.

He died six days later and was buried in Manbij, north Syria. Later, his daughter had her leg amputated. UNHCR Lebanon spokesperson, Lisa Abou Khaled, told Syria Direct they could not provide details “on individual cases.”

“UNHCR is deeply concerned about the increasing levels of despair of refugees,” said Abou Khaled, adding that the “cases of depressions, attempted suicide and self-harm amongst refugees have increased dramatically in the past few months in Lebanon.”

What to do when someone has suicidal thoughts?

In Lebanon, the suicide rate stands at 3.30 per 100,000 people, according to World Bank figures from 2016. But Makarem noted that many deaths by suicide go unreported due to “religious, legal and social issues.”

“One in four people in Lebanon will experience a mental health problem throughout their lives, but many perceive mental health as a taboo,” Makrem explained. “We need to normalize the conversation about mental health for people to be able to go to public hospitals or primary health centers and ask for psychological or psychiatric support,” she added. “In our community, especially for men, it is even more difficult to express if they are experiencing any mental health problem because they are supposed to be strong.”

Some of the warning signs of people with suicidal thoughts include feelings of hopelessness and loneliness. “If they don’t look forward to specific goals and don’t have a purpose in life, if they show an increasing dependence of alcohol or drugs or if they are not able to carry simple daily tasks such as going to work or getting out of bed,” Makarem explained. If the person shows mood swings, episodes of extreme rage, or increasingly talks about death, these are also warning signs to consider. Other signs are more explicit like “posting a note of self-harm, sending farewell messages or giving their belongings to their loved ones.”

When someone shows these signs, Makarem recommended trying to “create a safe space and tell them we are there to listen, because sometimes people just need to vent.” She added that one should avoid judging them, “making them feel guilty for making such suicidal thoughts” or “directly jump into giving them solutions and what should they do.”

Call Embrace Lebanon suicide prevention hotline 1564 if you are in distress. For more information on warning signs and what to do when a close person seems at risk, click here.

This article was updated on 22/02/2021 to correct the age of Haitham.