Despite societal and financial hurdles, Idlib’s women persevere

One of the largest barriers to womens' professional advancement and ability to support the family in Idlib is a lack of investment in women and their training facilities.

10 November 2019

AMMAN — Fatima al-Ahmad was visiting her sick mother in the town of Kafr Nabel, in the countryside of Idlib province, when a rocket launched by the government forces hit her house in 2017, killing her husband and their four children.

“I fainted and was taken to a field hospital,” the 39-year-old housewife told Syria Direct. “I spent six months riddled with anxiety that kept me up at night, and fell into a depression that lasted one year. This is the greatest agony of my life.”

Later, however, she joined several first aid and nursing training courses and dedicated her life to assisting and rescuing the injured with the Syrian Civil Defense Teams (White Helmets).

“I gained a motive to rescue any life, even if it would cost me my own,” she said.

According to the spokesperson for the Civil Defense Directorate in Idlib, Ahmed al-Shekho, the participation of women in medical services has helped a large portion of civilians, especially women, children and elders. He indicated that “the number of first aid female responders of the Civil Defense Directorate in Idlib has reached 144 volunteers.”

Another tragedy unfolded in the life of Aisha, a 35-year-old mother of two.

On April 10, 2013, Aisha’s husband left Idlib for work as usual. An English teacher in the city of Hama, he was never too far out of reach so when Aisha called and wasn’t able to connect to his phone, she knew something was wrong.

“I tried to call him many times, but his cell phone was switched off,” she told Syria Direct. “I called the school and they told me that he never arrived. I was certain that he got arrested at one of the regime’s checkpoints between Idlib and Hama. I felt like I had lost him.”

With no idea about her husband’s state or whereabouts, Aisha started digging for information but only influential people in the province had the answers she needed and it wasn’t free.

“I didn’t have a fraction of the money that they were demanding,” she said.

A year after her husband’s disappearance, Aisha started looking for a job to support her two children. She moved out of her house because she wasn’t able to pay rent, moved in with her mother in Idlib and began looking for ways to support her family.

“I visited my mom’s friend who worked as a tailor and took a workshop where I learned the principles of the craft. She helped me with money. I bought a sewing machine and began working out of my mother’s house,” she said. “I am currently the only breadwinner in my family. In the morning I sew, and in the evening I weave wool and knit. I try to work days and nights so I can provide my children with what they need.”

Since then, she has learned new ways of establishing a sewing profession and developing her business to generate a higher income.

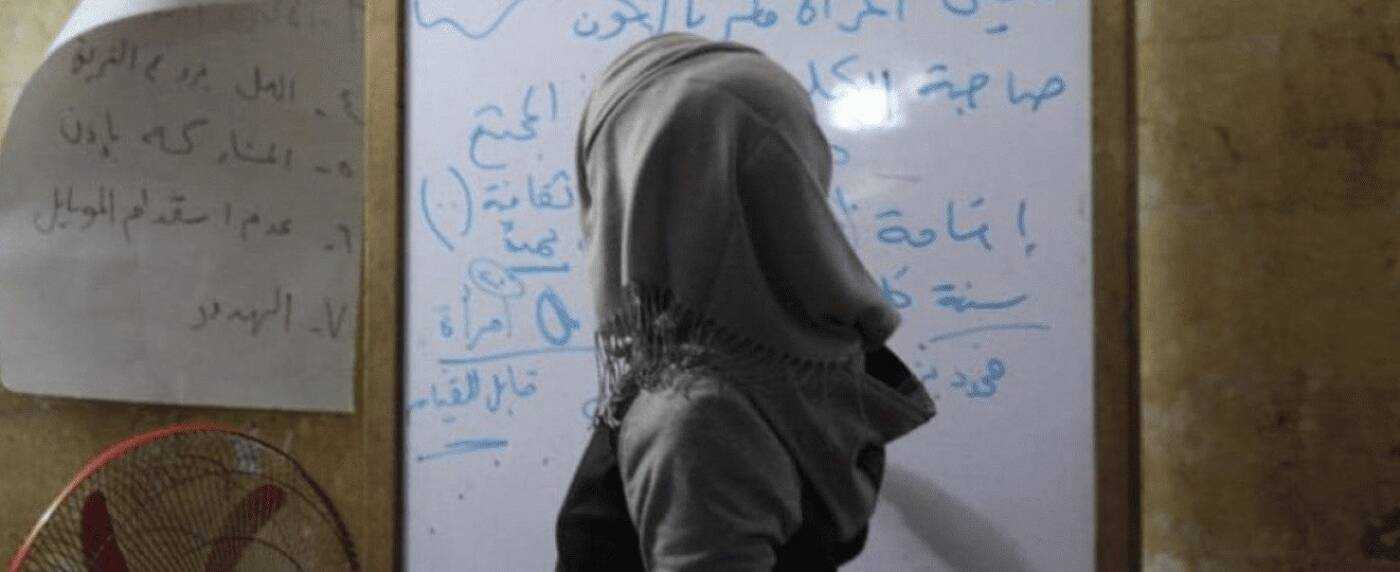

Moreover, Aisha joined the team of trainers of the sewing division in the office of the Women’s Union for Women and Child Welfare, which was set up less than a year ago by a group of female volunteers offering free training courses for women, without any outside support.

From time to time, “the women call me when they want to learn [sewing] and I offer what I have happily,” she said.

Although there is a segment in society that rejects women working for themselves and their families, according to Aisha, the reality is that one needs a livelihood and the absence of men in many instances “necessitates a woman to work. She plays the role of both father and mother at once with the loss of a husband.”

Endless Challenges

A sudden shift in the role of women in wartime is difficult in itself but cases like Rawan’s, a 25-year-old who collects small gravel to sell to construction workers, reflect the severity of the situation in Idlib.

“I go out early in the morning while everyone is asleep and collect as many as I can and carry them in my dress,” Rawan narrated to Syria Direct. “Then I take it to construction workers so that I can make one dollar for every load.”

Rawan supports her husband, mother and child and lives with them in “a small room that has been eaten away by the intense humidity” in the city of Kafr Nabel, she said.

In addition to working and providing for her family, Rawan assists her husband, who was hit by rocket shrapnel two years ago and suffers from Spinal muscular atrophy with lower extremity predominance, and persistent neurological convulsions, requiring a periodic sedative in addition to other medical supplies.

Before collecting gravel, Rawan worked in a kindergarten supported by Mazaya Women’s Center in Kafr Nabel until the funding to the Union of Revolutionary Offices ended at the end of March 2018, as a result of American President Donald Trump’s administration’s decision to suspend around $200 million in aid intended to restore stability in Syria. The Union was one of at least 150 organizations with funding cuts due to that sudden decision. More than 650 employees lost their jobs.

Several donor organizations had also ended their funding to local organizations in Idlib after Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) gained control of the province in mid-2017, and later established the so-called Syrian Salvation Government (SSG).

Persistence triumphs the lack of funding

The core of Mazaya Center was formed in the house of Ghalia Rahhal, where women from Kafr Nabel were gathering for rehabilitation. In 2013, Rahhal asked Raed al-Fares—an engineer who was supervising the Union of Revolutionary Offices until he was killed along with his friend, Hmoud Juneid, by unknown men—to set up a department for women that she can supervise and promote the institutional role of women.

“There was no interest in women at the time, especially with the spread of societal and factional repression, mainly extremist groups. This put me in a challenging position to open Mazaya because I knew that we have women with great potential. They should have been invested in so that they can improve their conditions and society. We have already changed the lives of many women for the better, both financially and psychologically.”

The center provided training courses in all the fields women needed: professions, languages and media. But the largest barrier to the work of women-centered centers in Idlib province is funding, Rahhal said.

“I got core funding through my personal connection with Mr. Raed, may he rest in peace, but there is no international organizational support specifically for women. We were forced to close the center after the funding was cut,” she said.

In the absence of funding, a group of female civil society activists initiated the Saraqeb Women’s Union less than a year ago to provide awareness-raising activities for women on the upbringing of children and the problems they face. They held sewing and beauty courses for women and language courses for children.

The idea of the union developed “from observing a large number of female heads of households after the loss of a husband or breadwinner,” head of the union lawyer Salma Abbas told Syria Direct: “I became excited to turn women from consumers into productive members of society without waiting for material help from anyone, especially widowed women and wives of detainees.”

Also, since mid-2017, the Syrian Women’s Assembly began its activities in Maarat al-Numan in cooperation with the Idlib Province Council. “Empowering women,” according to the director of the association, Huda Sarjawi, can be achieved through providing “a safe environment in which women can exercise their rights, and establish effective women’s groups, implement educational and professional projects for women, and provide the opportunity to pursue education for those deprived of it.”

She stressed that “the gathering is not exclusive to Maarat al-Numan alone and is for all women’s centers in the liberated towns of Idlib [controlled by the opposition].” Although the assembly has not received support, female volunteers are helping each other conduct training courses in women’s career fields on an ongoing basis, such as tailoring, weaving and general education classes; they are tailored to the preferences of women and what serves them in their working lives.

“All material secured at the center is by personal initiative; women bring them for training,” Sarjawi said, adding that the assembly collects new and used clothes from members and their families to give to beneficiaries, and organizes a product exhibition and some awareness sessions for women’s centers.

“Women’s assemblies promote the role of women by granting them the opportunity and confidence to express their views, ideas and voice, and allow them to bring their children with them to spend time in kindergarten while the mothers finish training,” Rawan said while drawing attention to the fact that the number of these centers is limited.

In this context, Salma Abbas argued that women are completely marginalized in terms of international support. In cases where partial funding to support women has been provided it is referred to as psychosocial support.

“The majority of women [in Idlib province] are tired of attending psychological support training. We no longer need psychological rehabilitation as much as we need intellectual, practical and scientific rehabilitation to advance the remaining women in society,” she said.

“Even in my center and through my monitoring of womens’ concerns, most of them have a desire to learn new skills and methods. We, as women, are not ignorant. The majority of us are cultured and only need a logistically and psychologically appropriate environment to be empowered.”

This article was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Nada Atieh.