Perspective: Of pro-regime marches and freedom demonstrations: Two decades of reshaping a Syrian human being

On the twelfth anniversary of the Syrian revolution, our reporter Walid Al Nofal reflects on his personal experience.

18 March 2023

It was early morning, the day after the Syrian People’s Assembly swore in Bashar al-Assad as president on June 17, 2000. The Syrian Constitution was already amended, the minimum age requirement tailored to match that of the former president’s son. Our teachers at the 1st Primary School in my city, Inkhil, north of Daraa, led us in a march like a flock of sheep, cheering and shouting for the new president and the Baath Party. In our hands, we carried a picture of the two Assads: father and son.

I was five years old, in what is popularly known as al-mustamaa, an informal preschool class before the first year of school, usually reserved for the children of teachers and their relatives. This little herd I walked in, that I learned seven years later was called a “march,” to me was just a noisy event. I did not understand what was happening around me, why the children were going out or even what we were shouting for.

That day, we came out of the western door of the school, walked around for a few minutes, then returned from the eastern door to go back to our classes. From then on, a picture of the new president was posted above the blackboard. On its right was a picture of Assad the father, and on its left a map of the Great Arab Nation, which one day would bar me from entering most of its countries because of my nationality.

Seven years later, we were called again to a new march. This time, I was in the sixth grade at the 5th School in Inkhil. We marched in support of Assad the son, in the presidential referendum held in May 2007.

The principal gave me a painting to carry, with the slogan of the Baath Party, “One Arab Nation, Bearing an Eternal Message,” inscribed on a map of the Arab world. My friend Khaled was given a picture of Hafez al-Assad. We were to walk at the front of the march. We all went together, chanting false pledges to give our soul and blood for Assad, roaming the city’s streets.

On the way, Khaled began to point his middle finger at Assad the father disparagingly. He only meant to provoke the laughter of those around him in the crowded march. The principal saw, and fell upon him, beating and curing him, threatening to tell his father. I did not understand this severity at the time. But I would learn fear well at the Baath schools, from this incident and others that followed.

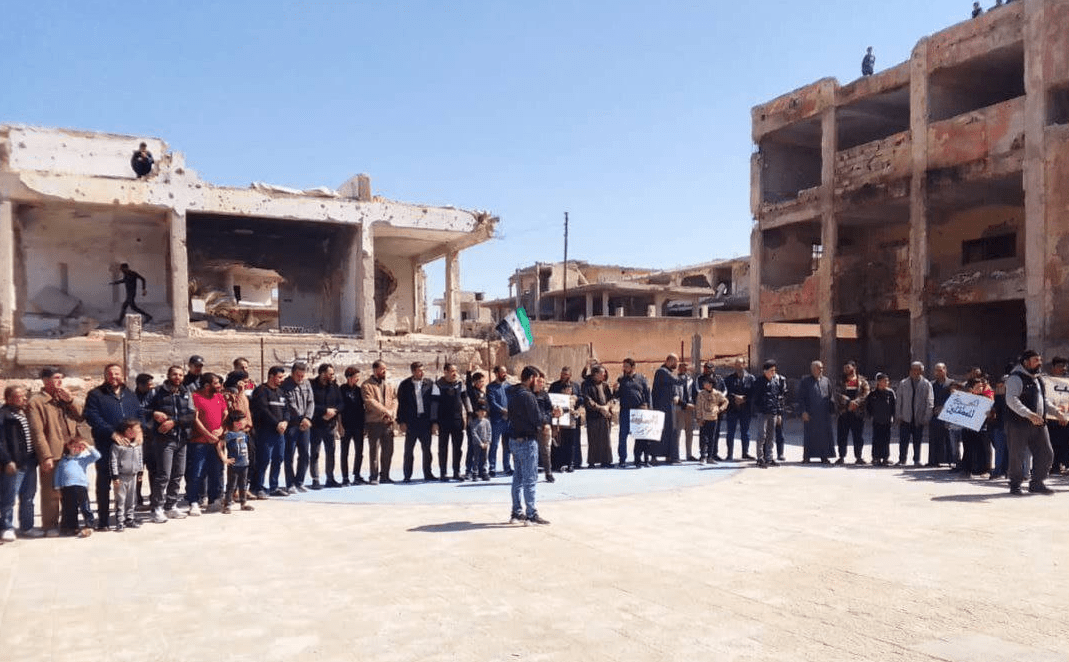

On March 21, 2011, dozens of men, young and old, gathered in al-Bassam Square near our home in the center of the city. It was the first demonstration Inkhil saw. The people began to cry out: “freedom…freedom,” and “glad tidings from the Houran.” I shouted like the others in my city, but I did not have a clear concept of “freedom” and the “republic of silence and fear” I lived in. On that historic day in my life, the dividing line between two completely contradictory eras, some qualified men in the city spoke about the injustice of the Baath party, the brutality and domination of the security forces and the humiliation of the Syrian as a human being. All of it seemed new to me, and a set of questions puzzled me. What was the homeland? And human dignity? Why were the army and security forces killing their people?

The next day, my friends at school and I planned to chant for besieged Daraa al-Balad in the courtyard of Martyr Oqla al-Zahra High School. After a few minutes of this little demonstration, we were brought to the office. The principal began to reprimand us, threatening to bring the security services for us and our families. The mukhabarat prisons would teach us.

I realized well then that the Baath schools would only ever create slaves, that the homeland is human dignity and freedom of opinion. I realized the barrier of fear had broken since the first drop of blood was shed in Daraa al-Balad, and that change is a national duty that no free person can set aside. I committed myself to that.

Since that time, I did all I could to gain my freedom, and that of my country’s people, from Baath schools and rule. On January 24, 2012, I brought a large Syrian revolution flag to school, and raised it in place of the regime flag on the flagpole on top of the school building, in view of Assad’s snipers at the Cultural Center checkpoint. They summoned the principal, ordered him to bring the flag. That day, his house was raided, and he was detained for three months. I have never blamed myself for anything more than this.

Rebuilding a Syrian is no easy thing. For the sake of that, I lost many of my friends to the regime, to its prisons. The list, may God have mercy on them, goes on and on. I have been exiled twice, ending up the “foreigner” I always spoke to myself about when studying diaspora literature in school.

Today, after 12 years of freedom, I have learned well that investing in humanity is the first thing we must do. I have learned that restoring the homeland is the most noble thing a human being can devote himself and his time to. I have learned the detainees are a trust, and that the blood of the martyrs is a path. And I have learned that the greatest injustice a person can do to himself is to live without a cause to defend.

**

This article was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.