Preserving heritage? Permits to restore Old Damascus homes elusive without ‘influential contractors’

In the Bab Srijeh neighborhood of Old Damascus, residents say municipal permits to restore decaying buildings are elusive, but contractors with government connections hold the key.

18 July 2023

DAMASCUS — In 2013, when opposition forces took control of Damascus’ Yarmouk camp and regime forces placed it under siege, 55-year-old Hussam and his family decided to leave. They had somewhere to go: his abandoned family home in Old Damascus. A century old and empty for years, it offered shelter, and the family moved in.

The house was in disrepair, but Hussam—who asked to be identified only by his first name—could not afford to rent elsewhere. So the family stayed in Bab Srijeh, an ancient neighborhood in the Qanawat area of eastern Damascus known for its historically and commercially prominent market.

Hussam’s family house is showing its years. The 150-square-meter building “has some cracked walls and rainwater seeps in,” he told Syria Direct. Over the past two years, inspired by the growing movement of restoring and preserving architectural heritage in Damascus’ old neighborhoods, he began to consider “renovating the house, while maintaining its historical features.” But when he sought out the necessary permits, he ran up against “the municipality’s obstruction.”

After four months of trying to get a restoration permit from Damascus province, Hussam was referred to the Bab Srijeh municipality earlier this year. There, an employee “suggested that I hire a contractor to facilitate the restoration process, saying my house is situated in a heritage area requiring approval from multiple agencies, including the Antiquities and Museums Directorate,” he said.

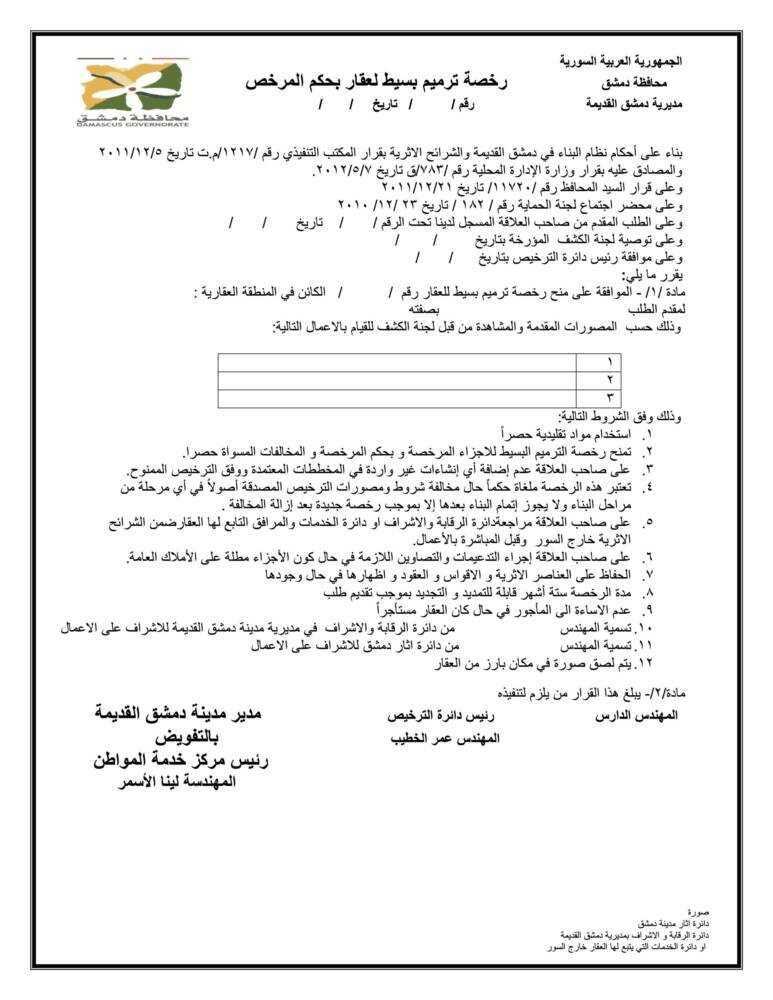

Typically, the Old Damascus Directorate, which is part of the Damascus Provincial Council, grants restoration permits. These require the use of traditional materials and prohibit the addition of any construction not included in approved plans. Before beginning restoration, the property owner must also consult the Central Authority for Supervision and Inspection or the Department of Services and Facilities the property falls under if it is in a heritage area outside the walls of the old city.

The permit holder must also preserve the property’s original features, including arches and ribbed vaults. An engineer from the Central Authority for Supervision and Inspection in the Old City of Damascus, as well as an engineer from the Antiquities Directorate, must be appointed to oversee the project.

A model property restoration permit for areas administered by the Old Damascus Directorate.

Most buildings in Bab Srijeh need repairs and restoration, but their owners, like Hussam, “struggle to obtain the necessary restoration permits due to overlapping procedures involving multiple authorities: the province, the municipality and the [Ministry of] Endowments,” a source from the Bab Srijeh municipality told Syria Direct, requesting anonymity for security reasons. “Bab Srijeh is considered a heritage area, a Roman city.”

Hussam disputes the municipality’s description of his home as lying within a heritage area. His green tabu title deed—the strongest proof of ownership in Syria—makes no mention of the property being within such an area. In either case, he does not intend to alter the house’s architectural identity during the repairs. Still, the Bab Srijeh municipality has refused to issue him the restoration permit, while he refuses to move ahead with the restoration through a contractor connected to the municipality.

‘Corruption’ hinders the permit-granting process

Without a permit, Hussam has not been able to restore his house. But other construction and restoration projects have been approved in recent years that are changing the face of Bab Srijeh.

In 2021, the regime faced accusations of haphazardly rehabilitating the neighborhood’s market, despite its classification as a heritage area. The rehabilitation work was carried out by the General Company for Building and Construction, which falls under the Public Works and Housing Ministry.

Other neighborhoods such as al-Amara and Sarouja are also the site of a number of restoration efforts. Some include the conversion of old houses into multi-story buildings that deviate from the architectural character of Old Damascus. Hussam alleged that those carrying out such projects receive preferential treatment “since they are contractors with government connections.”

A new, multi-story building stands amid old houses in the Bab Srijeh neighborhood of Damascus, 25/4/2023 (Habib Shehada/Syria Direct)

Khaled al-Fahham, head of Syrians for Built Heritage, a Damascus-based civil society organization, said there is an administrative flaw in the permit-granting process. He suggested there is a lack of fairness and equality in the treatment of permit applicants, which he attributed to the complex web of regulatory bodies, systems and laws involved.

“The spread of corruption has created a system where legal permits are easily granted to certain people while others face obstacles,” al-Fahham told Syria Direct.

The source from the Bab Srijeh municipality, neighborhood residents and al-Fahham all contend that contractors connected with provincial authorities are able to obtain demolition and reconstruction permits for entire blocks in collusion with local municipalities–while others struggle to obtain basic restoration permits.

Hind, a 39-year-old Bab Srijeh resident, said her family encountered this dynamic in 2022, when the provincial government demolished part of their house that faced a side street. They were told the home posed a danger to pedestrians and public property as “it was on the verge of collapse, according to the province’s assessment,” she said. The demolition took place “without any prior warning.”

After the demolition, Hind tried to obtain a permit to restore the building, but was not able to “on the pretext that part of our house is a heritage element,” she said. When she objected to the municipality, “they told us the restoration must be done by a contractor” and “gave me the name of a particular contractor to contact.”

She approached the contractor, who charged two million Syrian pounds ($204 based on the current parallel market exchange rate of SYP 9,800 pounds to the dollar) to secure the restoration permit, which he successfully obtained, she said.

While restoring the house and rebuilding the portion that was demolished, the contractor “altered the house’s original identity,” Hind said. “He removed the fountain and used bricks instead of stone.” When the municipality sought to revoke the permit for violating its conditions, “the contractor resolved the situation by paying [a bribe to] the municipality.”

When the restoration of the 75-square-meter house was complete, the contractor demanded SYP 15 million, far beyond what Hind’s family could afford. In regime-controlled parts of Syria, the average monthly income is around SYP 100,000 ($10 based on the latest exchange rate). As a result, the contractor proposed to buy the family’s house and find them a property in another area, she said. Her family accepted the offer.

In addition to being able to obtain restoration and construction permits, she alleged contractors connected to provincial authorities can revoke restoration permits, often as a means “to pressure homeowners into selling their houses.” Hind added that the contractor she approached used this tactic with a number of the neighborhood’s residents, ultimately leading them to sell their houses.

Suspended development plans

Damascus province still uses the 1968 Écochard Plan, named for Michel Écochard, the French architect who developed it. The plan took the city’s needs up to 1984 into consideration, but remains in effect decades later.

“It is still the only one hanging on the Damascus Governorate’s walls,” al-Fahham said. The 1968 plan “determined the urban character of all areas in Damascus, but excluded Old Damascus,” the areas referred to as “inside the wall.”

The plan allows for the redevelopment of all properties in other parts of Damascus “without having to preserve the city’s cultural and architectural identity, and without regard to its artistic, aesthetic and civilizational values,” al-Fahham added.

In 2001, 17 years after the Écochard plan’s timeframe, the Syrian Housing Ministry’s General Company for Engineering Studies introduced a new master plan for Damascus. It defined the future needs of the city in terms of the size and density of its population. The plan suggested the construction of 205 residential blocks across 30,000 hectares of land to accommodate the projected population of 7 million by 2020.

In 2009, the Ministry of Local Administration signed a memorandum of understanding with the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) for the implementation of a three-year study on urban planning for sustainable development in the Damascus metropolitan area. JICA completed the first phase of the study between 2006 and 2008.

However, neither the 2001 plan nor the JICA project ever came into effect, and Damascus still spans an approximate area of 10,000 hectares as outlined in the Écochard plan.

When protests erupted in Syria in 2011, particularly near Damascus, discussions regarding redevelopment plans came to a halt. It was not until Law No. 10 of 2018 was enacted that the subject resurfaced. The law enables Damascus to create urban redevelopment areas across Syria. Human rights groups have expressed concerns about the law’s potential impact on the property rights of displaced people and those who are wanted by authorities.

Restrictions that do not safeguard history

An employee from the Old Damascus Directorate, who asked to remain anonymous, told Syria Direct the department’s licensing service is responsible for issuing building and restoration permits.

“The service grants three types of permits. The first is the emergency repair permit, which is granted within three days if there is damage to public property. The second is the simple restoration permit and the third, and most common, is the reconstruction permit,” the source added.

Applicants who wish to receive such permits must submit a set of documents, including proof of ownership, a subdivision plan (if applicable), as well as the building permit and plan. Obtaining some of these documents can be difficult in some cases, such as when the property is undivided among heirs or rented without a lease contract.

While restoration and reconstruction permits are meant to safeguard heritage areas, “the majority of those carrying out restoration and reconstruction permits violate the conditions of preserving the historical and architectural integrity of Old Damascus homes,” the source at the directorate said. Some contractors “use concrete in the restoration and build additional floors in violation” of the permits, the source added.

In response, al-Fahham highlighted the government’s failure to establish unified strategic plans and visions based on in-depth analytical studies. He emphasized the importance of considering factors such as historical and archaeological value, social and physical status and the complexities arising from properties with overlapping ownership.

He attributed the complexity of the restoration process to limited support from specialized agencies, such as the province and the Antiquities Directorate. This is further compounded by budget constraints and the absence of restoration studies. Additionally, companies with expertise in traditional restoration techniques and materials are rare, particularly those that work with wood: an essential structural element in many old houses.

Until a fair mechanism is established for the old city’s residents to restore their houses, Hussam lives in his aging home, waiting for a permit to repair it “while preserving its historical identity.” He sees permitted construction underway altering the character of the neighborhood, but refuses to work with connected contractors or attempt to bribe his way to a permit. Instead, “we are living in the house without repairs, although it is difficult,” he said.

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Nouhaila Aguergour.