Seized properties sold ‘dirt cheap’ in Afrin

In Afrin, there is a widespread trade in properties belonging to displaced residents known as “cost houses,” which are sold by Ankara-backed military factions and civilians for “dirt cheap” prices: the cost of repairs.

25 July 2023

PARIS — For the bargain price of $700, Firas Yassin bought a house in Afrin city at the start of 2023, ending two-and-a-half years of “homelessness, sleeping at the gas station where I work with no privacy or comfort.” In the northern Aleppo countryside, to which he was displaced from south Damascus in 2018, the unfinished building held the promise of stability: a place of his own.

Yassin did not buy the two-bedroom house from its original owner or through an intermediary. He purchased it from a civilian who, in turn, had bought it from the military faction that “seized the house” when Turkish-backed Syrian National Army factions captured Afrin and its countryside during Operation Olive Branch in early 2018.

He has no official documents proving ownership or guaranteeing any rights to the property in the future. This is why the house was such a bargain: the person living there before Yassin offered the house for sale at the cost he spent on restorations and repairs. In the Afrin real estate market, a property like this one is called a “cost house”: one sold not for its actual value, but for the work put into it.

Homes belonging to Afrin’s displaced original residents have been sold for cheap prices for years. Prices for such properties range between $400 and $3,000, well below their actual value. They are sold as “vacant” or “party houses,” the latter insinuating the properties belong to displaced members of the Democratic Union Party (PYD) or the Turkish Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The armed wing of the PYD, the Kurdish People’s Protection Forces (YPG), controlled Afrin before Turkey’s 2018 cross-border Operation Olive Branch.

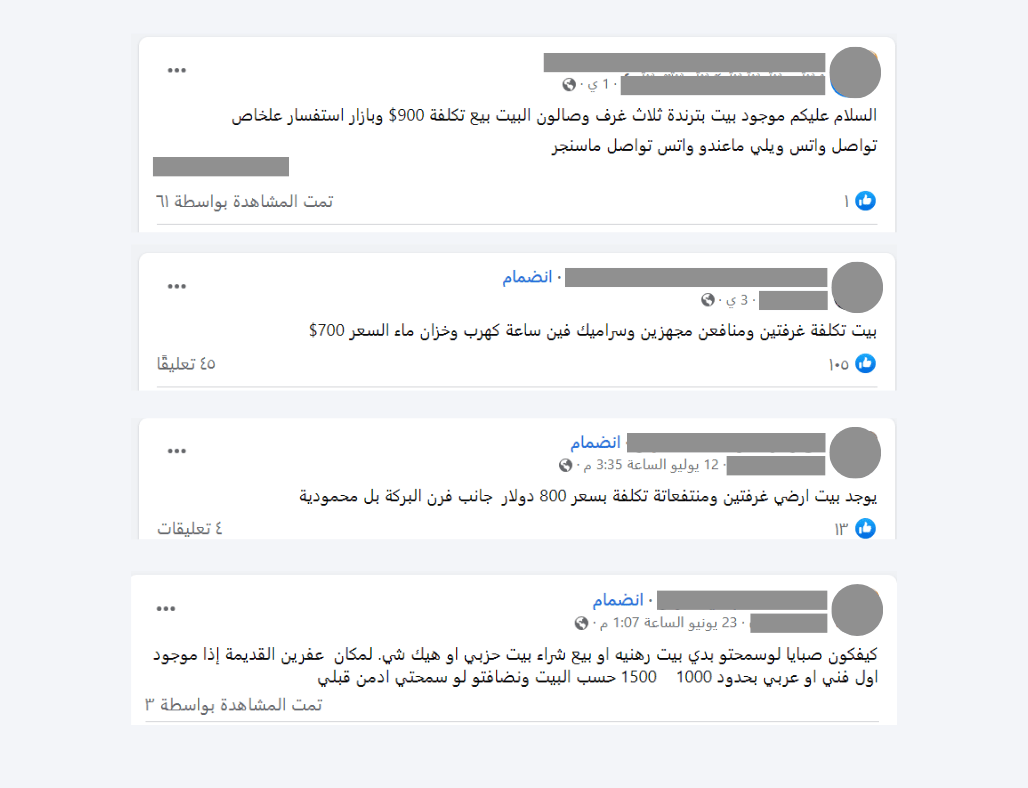

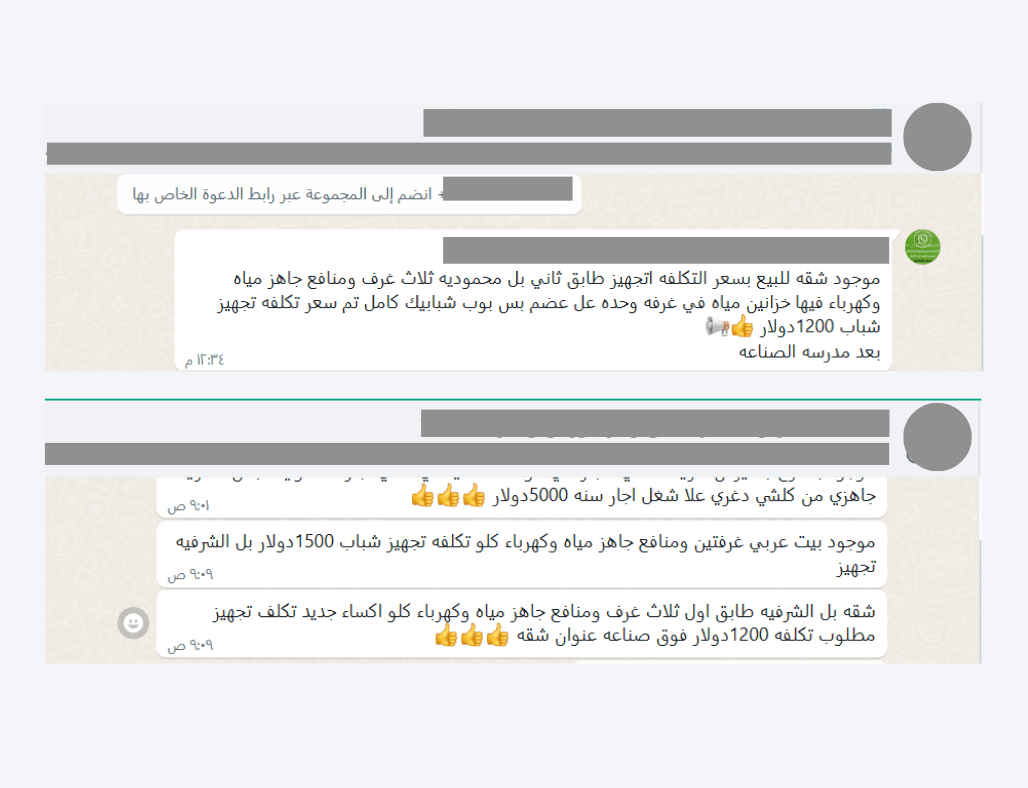

Throughout June and July, Syria Direct monitored a large number of advertisements for “cost houses” posted to social media and WhatsApp groups by individuals and real estate offices in Afrin. These posts—and additional communication with the sellers—confirmed that they were offering homes they did not own for nothing more than the cost of repairs.

Facebook and WhatsApp posts advertising houses for sale at cost in Afrin, May and June 2023 (Syria Direct)

‘Dirt cheap’

Yassin does not know who his house belongs to. The person who sold it to him claimed its owner was a member of the PKK, a group Turkey and the United States have designated as a terrorist organization. Ankara and the factions it supports largely consider the PYD and PKK to be one and the same.

He bought the house without entering into a contract, which is “customary in Afrin,” he said. Yassin has not heard of “a seller backing out, and if that were done it would be by mutual consent, and the money would be returned,” he said.

In the event the original owner of a property sold in this way returns—as has happened with other cost houses—the returnee is “persuaded to pay the costs of restoring the residence, or give a rental agreement to the person occupying it, provided the costs of maintenance and restoration are deducted from the rent,” Yassin said. For the house he lives in, he has paid to install windows and doors, paint the walls and lay sewer pipes, in addition to the original $700 sale price.

Yassin knows selling properties that belong to people displaced from Afrin when the SNA took control is a violation of their property rights. Still, he bought the house he lives in because of “the high cost of houses sold legally by their original owners.” As a displaced person, “I’m used to losing,” he said, so if the original owner returns, he plans to “return the house, and consider myself to have rented it for several months.” Despite the risk involved, the amount he paid to buy the property is the same as renting a house for a full year, as “a modest house rents for at least $50 a month,” he added.

Like Yassin, Abdulkarim al-Hamad knows that one day he will likely have to leave the house he bought in 2021. Al-Hamad, who was displaced to northern Syria from Daraa province in the summer of 2018, purchased the property directly from an SNA faction.

from an SNA faction in 2021. “The seller is not the original owner,” he told Syria Direct. “I have no right to it, and will hand it over to its owner if he comes back.”

Al-Hamad bought the freestanding house in Afrin for “dirt cheap,” as he put it. “The real value of the house is multiple times what I paid.” Buying it was a “temporary” solution “to be free of high rents and the exploitation of real estate offices,” he said.

When al-Hamad received the house, the faction he bought it from pledged that “I would remain under its protection, and that I could resell the house to someone else, provided I informed them of the sale,” he added.

Rights violated on both sides

In 2021, Abu Said was the third buyer of a cost house in Afrin. Six months later, he had to vacate the property when its original owner returned. He believes he was “scammed by the seller, a military commander.”

Abu Said, who was also displaced from Daraa in 2018, bought the house for $1,300 under its designation as “spoils” that belonged to a member of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) who fled the area. But after buying the house and paying $350 in maintenance costs, he learned it actually “belonged to an elderly Kurdish man, who returned to Afrin to claim his property.”

Abu Said returned the house to its owner “without any compensation.” While he always knew the house would return to its true owner one day, he did not expect that day to come so soon and feels his “rights were lost.”

More than five years after Ankara-backed opposition forces captured Afrin, “the phenomenon of selling the original residents’ homes continues, but it is not like it was in the first three years,” Abu Anas, the owner of a real estate office in Afrin, said. “Some of the military factions are the ones running the market.”

While there is a brisk trade in these properties, Abu Anas—who asked to be referred to by a pseudonym for security reasons—does not deal in them, “to avoid people losing their rights,” as he put it.

‘We guarantee your rights’

Below a Facebook post advertising properties for sale in Afrin published on May 29, one user commented: “I have a cost house at the al-Saraya roundabout, for a final price of $600.” Syria Direct contacted the poster, who hinted that he was open to some negotiation and sent a video recording of the house.

A video of the al-Saraya house sent to Syria Direct by its seller.

Every day, on a WhatsApp group bearing the name of Abu Abdulrahman’s (a pseudonym) real estate office in Afrin, at least five advertisements are posted for residences selling for less than $2,500. Many belong to people displaced from the area.

On July 6, Abu Abdulrahman sent a voice recording to the group: “We have a three-room third-floor apartment at the Nowruz roundabout with water and electricity.” He added that the house was finished, except for one room, and that he was selling it for $1,600 along with its furniture. Minutes later, in another recording, he advertised “a ground-floor, two-room apartment on al-Serfis street with water and electricity for $1,800,” furniture included.

Syria Direct’s reporter reached out to Abu Abdulrahman as a prospective buyer, and asked for more details about the two advertised properties, including their ownership. Abu Abdulrahman responded: “The original owner of both properties is not present, and the house is priced at the cost of furbishment,” indicating that the asking price was not the actual value of each property.

“The house is currently occupied by a civilian, not military personnel. He spent some money to furbish it, and wants to sell it,” Abu Abdulrahman added. He offered to show the two properties in person before any purchase was made.

When asked about documenting the sale, the real estate dealer said “I guarantee your rights. I will give you a paper as a contract between you and the seller—we write the cost price that you paid for it.” He explained that what was being sold is “the cost, not the house.” In the event the property’s original owner returned, “I guarantee you will stay in the house until you get your money back.” In any case, “it’s a better deal than renting,” he said.

In a second WhatsApp group, named after a real estate office in Afrin owned by Abu Samer (a pseudonym), the dealer advertised an apartment in the al-Ashrafieh area of Afrin city. The two-bedroom apartment was newly outfitted with doors, windows and access to electricity and water, and available “for $1,200,” he said.

A screenshot from a WhatsApp group showing advertisements for an apartment being sold at cost in Afrin. 5/7/2023 (Syria Direct)

Syria Direct’s reporter reached out to Abu Samer as a potential buyer, and asked for more details about the property. “Its original owner is not present, but the house is occupied by a civilian,” Abu Samer replied. He confirmed that the sale price was the “cost price” of the apartment.

Like Abu Abdulrahman, Abu Samer gave assurances of providing a document proving payment for “the cost.” He also sent a video showing the apartment and its layout.

A video of the al-Ashrafieh apartment, sent to Syria Direct by the owner of a real estate office in Afrin.

Such assurances are “just words on paper,” an Afrin-based real estate lawyer told Syria Direct. “If the original property owner returns and claims their rights through the court, it must be returned, and the buyer is owed no compensation,” he added, requesting anonymity for security reasons.

At best, “the buyer can look for the person who sold it to him, but most often the seller is a military faction, and this means he will not get his rights back” in the form of compensation, the lawyer said.

The practice of selling real estate in Afrin under the pretext that it is a “party house,” or affiliated with the Kurdish parties that controlled the area before 2018, is widespread in Afrin, the lawyer explained. There are “many homes that have been sold several times, from person to person” without the knowledge or consent of their owners.

A battle to reclaim real estate

Before 2011, there were an estimated 200,000 Kurds in Afrin, making up 92 percent of the area’s population. Today, they make up just 20 percent of the population, according to Shar Magazine, a Kurdish news site opposed to the Turkish-backed SNA.

Afrin’s Kurds—both those who refused to leave the area when Ankara-backed factions moved in and those who fled but returned years later—face particularly extensive challenges when attempting to reclaim their residential and commercial properties.

Ahmad Suleiman’s fight to reclaim his real estate in Afrin began before 2018, when the YPG still controlled the area and seized shops he owns in downtown Afrin. When the SNA captured the area in Operation Olive Branch, they seized the 55-year-old’s shops from the YPG.

Weeks after Turkish-backed factions took control, Suleiman, who is Kurdish, filed a legal complaint with the SNA-affiliated Free Police in Afrin. As a result, he regained his shops, one of which had been seized by a commander from the SNA’s Northern Brigade, which took part in the battle for Afrin.

But in June 2018, the Northern Brigade detained Suleiman under what he called a “set of malicious charges,” such as “bribery, collaborating with Russia and holding a false [property] certificate.” The charges were an attempt to put pressure on him and usurp his property once more, he said, “which is what actually happened.”

While he was being held, the SNA’s Hamza Division also seized Suleiman’s farm, with his house, furniture and farm equipment valued at around $20,000. His wife, Fidan Bakir, was thrown out of the property.

Five months later, Suleiman was released, but his property was not returned. He later turned to the Grievance Redress Committee, a local committee formed by the SNA in September 2020. In 2021, three years after he was detained and one year before the committee dissolved itself in November 2022, Suleiman was able to reclaim his shops in Afrin city. He received no compensation for the years during which the Northern Brigade held his shops and used them as an exchange company.

Suleiman’s farm, located on the outskirts of Jenderes, is still held by the Hamza Division, while he lives with his wife in a small apartment in Afrin city that he rented four years ago.

In a similar story, the SNA’s al-Waqqas Brigade seized the family home where Siamand’s (a pseudonym) father lived in the Afrin countryside when they took control of the area. His family was expelled from the property, he told Syria Direct.

In 2021, the al-Waqqas faction left the village, only to be replaced by the notorious Sultan Suleiman Shah Division. The faction, known locally as “al-Amshat” for its commander Abu Amsha, settled in the village and properties previously occupied by al-Waqqas fighters.

The family demanded their house be returned to them, but al-Amshat stipulated they pay $2,000 to reclaim it, which they cannot afford. To this day, Siamand’s relatives live in his small house, while a fighter occupies the large family home, he said.

Selling by proxy

Facing extensive violations, many displaced Kurds have tried to sell their properties back in Afrin to minimize their losses. But even as legitimate owners selling their properties, they face challenges: the sellers are not physically present in Afrin, and Afrin has no real estate registry.

Even before 2011, Afrin’s cadaster—an official register documenting the size, location, ownership and changes to all properties—was located in Aleppo city, due to “the regime’s desire to tighten its grip on real estate sales in border areas by imposing a system of security approvals,” the real estate lawyer in Afrin said.

Once the opposition took control of the area, the lack of a real estate registry in Afrin aggravated and multiplied real estate problems, especially in the absence of a large percentage of the original population. Residences that have not been seized can be sold “through a lawyer proxy, if the property owner is outside the area,” the lawyer said. But “this is judicial representation, not authorized in the real estate departments,” he explained. “The lawyer can confirm the sale in court, but can’t document ownership in the real estate registry.”

Because Afrin has no real estate registry, “there are no lawsuits to establish ownership” in the area, because “a property ownership claim needs to refer to the cadastral certificate, which is not there in the first place,” the Afrin-based lawyer explained.

Therefore, all proxy property sales in Afrin are “legally unsound, and cannot be relied upon to prove ownership,” he added. This means that “many real estate issues will not become apparent now, but will appear later after the original inhabitants return, if there is a change of the controlling forces or a political solution is imposed.”

He pointed to the real estate crisis that East Ghouta witnessed after the regime regained control of the area outside Damascus in March and April 2018. Damascus did not recognize sales in the area, though they were documented in the opposition-affiliated Douma real estate registry, which “based its work on the regime registry that was there in the first place,” he said.

When Damascus took control, it “denied some real estate sales, or [claimed] that they were carried out by armed force, even though they are legal and documented,” he said. In Afrin, with no local real estate registry to begin with, an even greater crisis would be likely.

A temporary real estate registry?

One official source at one real estate registry department in the northern Aleppo countryside revealed to Syria Direct that he and a group of other lawyers had submitted proposals and solutions to establish a temporary real estate registry in Afrin.

They proposed to “confirm [property] ownerships based on documents submitted by the owner once they are verified with the assistance of experts. It is an approach that was applied in Azaz, and proved successful,” he told Syria Direct, requesting anonymity. But their efforts regarding Afrin have so far come to nothing.

The source noted the Afrin Local Council does have a real estate office, but it is “inactive,” which the real estate lawyer in Afrin also confirmed. “Preventing the establishment of a real estate registry in Afrin is systematic,” he said. “There are those who do not want it to be realized.”

Muhammad Haj Abdo, a lawyer and member of the legal office of the Afrin council, said the body “does not regulate real estate sales, whether the owners are present or not.” He noted that some people have filed complaints with the council, “thinking we are the competent authority to prosecute those who sell their relatives’ properties.”

Haj Abdo justified the council’s lack of oversight of property transfers in the area as being due to the area’s “chaos and lack of a cadaster, which is with the regime.” He also cited “the spread of forgery, and many owners being in fear or under threat.” The role of the council’s real estate office is “limited to regulating rental contracts,” he added.

To prevent additional real estate issues, the Afrin lawyer advised “anyone who wants to buy a property to buy it from the original owner, in order to guarantee his rights whether the de facto authorities remain or change.”

Haj Abdo compared real estate offices that trade in the properties of displaced people to “shops selling weapons.” He stressed that “they are not licensed, but we can’t shut them down because the council does not have the executive power to impose the implementation of its administrative decisions.”

Real estate violations currently taking place in Afrin violate international covenants and charters such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and others that emphasize the “right to property, and the prevention of arbitrarily depriving anyone of property,” said Riyad Ali, a legal advisor at Syrians for Truth and Justice, which documents violations in northern Syria. He noted that “the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court of 1998 considered such violations in times of war to be war crimes.”

This report was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.