Suwayda protesters resolute despite regime military reinforcements

Suwayda’s protest movement—marked by a prominent role for women and an insistence on nonviolence—is holding strong nearly 10 months in, despite Damascus deploying military reinforcements and appointing a man accused of war crimes as governor of the southern province.

5 June 2024

SUWAYDA — Last Friday, like every Friday, men and women flocked to Suwayda city’s downtown al-Karama (Dignity) Square for a central demonstration. More than nine months after Suwayda’s protests began, demonstrators still hold firm to their demands—including the “fall of the regime”—in defiance of Damascus deploying military reinforcements and replacing the southern province’s governor.

In late April, the Syrian regime deployed military reinforcements to Suwayda. The following month, President Bashar al-Assad replaced its governor, Bassam Mamdouh Barsik, with Major General Akram Muhammad governor, as part of measures that changed the leadership of four of Syria’s provinces.

Muhammad, the new governor, is from Homs province—not Suwayda—and has had a career as a top officer within Syria’s General Intelligence Directorate (State Security). He is accused of committing war crimes while heading up multiple security branches where his subordinates tortured detainees to death.

After months of ignoring Suwayda’s uprising, the regime’s recent moves—at least as portrayed by its media machine—signal that it intends to put an end to demonstrations in the Druze-majority province.

Read more: As Assad ‘ignores’ Suwayda’s uprising, what is the movement’s future?

In reality, “the regime cannot launch a military operation in Suwayda,” human rights activist Raya Subaie told Syria Direct. “The regime plays on the card of protecting minorities, and since Suwayda is less religious, a military attack on it would burn this last card, which it uses to negotiate internationally,” she added. Any decision to attack, moreover, “is not only in its hands, but also depends on its allies, Russia and Iran.”

Short of direct violence, “the regime could try to spread fear and terror by putting out rumors about the presence of the [Islamic State] IS in the area, or launch a media war against the men and women demonstrating in al-Karama Square,” Subaie said.

Suwayda’s protests—the longest, most organized and widespread in the province’s recent history—began in August 2023, in response to a number of government decisions, including to lift fuel subsidies. Early protests developed into a general strike in the private sector and state institutions, before economic demands became political: calls for the implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2254, the release of political detainees and, above all, Assad’s departure.

Suwayda’s movement has been marked by the active participation of women and demonstrators’ insistence on peaceful demonstrations, leaving Damascus at a loss over how to deal with it. Through regime-affiliated community leaders, Damascus has worked to win over the movement, promising to prioritize Suwayda over other provinces by increasing its share of fuel and electricity and canceling prosecutions against its opponents from the province.

With the failure of this policy of appeasement and the futility of ignoring the movement, regime forces have turned to violence, or the insinuation of it. At the end of February, security forces opened fire to disperse demonstrators in front of the settlement center in Suwayda city, killing demonstrator Jamil al-Barouki. Two months later, military reinforcements rolled into the province.

Suwayda’s movement continues

Ever since Suwayda’s protests first broke out last year, activist Subaie has been eager to participate. For the first three months, “I was there every day,” she said. The protests “represent me, accomplish my demands and express the justified demands of Syrians.”

The entry of regime reinforcements raised “concerns and questions” for Subaie “about the reason for them and how they would deal with the movement,” she said, but did not dampen her decision to continue protesting. The forces that entered Suwayda “are stationed at their designated military locations” and have not disrupted demonstrators’ movement so far, she added.

Sources from Suwayda told Syria Direct that reinforcements arrived at the Thaala and Khalkhala Military Airports, as well as to military security and air force intelligence branches.

Religious authorities and local factions may also have played a role in limiting the armed reinforcements’ role and impact on demonstrators. After they entered, several meetings took place between Suwayda’s religious, military and social leaders. This included a meeting between Sheikh Yahya al-Hajjar, the leader of the Men of Dignity movement—the largest military faction in Suwayda—and Sheikh Hikmat al-Hijri, the spiritual leader of Syria’s Druze, on April 30. In the meeting, al-Hajjar stressed that “escalation by any party whatsoever is unacceptable.”

While actors in Suwayda renewed their emphasis on the province’s refusal to be dragged into armed conflict, local factions announced they raised their readiness in anticipation of any military operation.

Suleiman Abdulbaqi, the leader of Suwayda’s Ahrar Jabal al-Arab faction expressed his group’s support for the demonstrations, telling Syria Direct “the movement will continue until its legitimate demands are met.”

As journalist Hamza al-Mukhtar sees it, the arrival of military reinforcements played a “positive role for the people of Suwayda.” It “brought people together, increased their solidarity and gave momentum to the demonstrators in al-Karama Square,” he said.

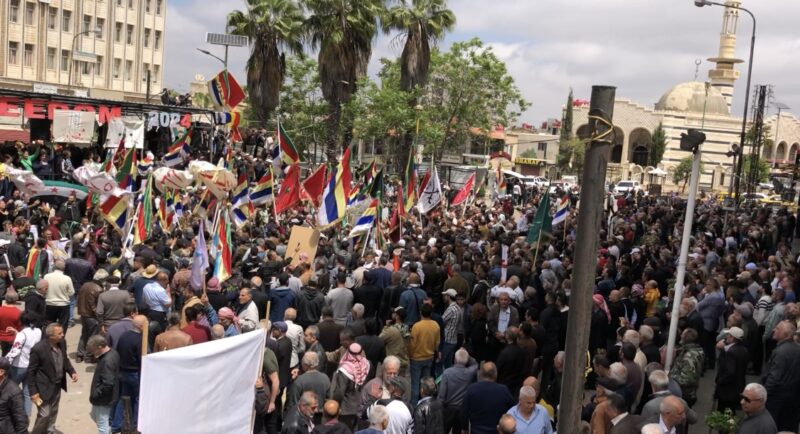

Hundreds of demonstrators gather at Suwayda city’s downtown al-Karama (Dignity) Square days after Syrian regime military reinforcements arrived in the southern province, 3/5/2024 (Nour al-Nashit/Syria Direct)

Contrary to Damascus’ likely intentions, the show of force increased “people’s motivation to continue in their stance, without retreat,” al-Mukhtar said. “Demonstrations come out daily, and al-Karama Square has not been emptied despite the security, economic and weather conditions.”

Activist Marwan Hamza downplayed the significance of the appointment of a new governor for Suwayda “with a history of torturing and persecuting Syrians.” Muhammad’s governorship “will not alter the equation, because he is commanded by security agencies higher than him,” he said.

‘Women are the heart of the movement’

Suwayda’s women play an important role in the province’s uprising, “leading the movement,” one activist participating in the demonstrations told Syria Direct on condition of anonymity for security reasons.

“Women are the heart of the movement. They always participate in all the initiatives, including the big and important ones,” she said. This comes from a belief that “stopping could leave a gap, and this gap could stop the movement.”

Like al-Mukhtar, the activist said the deployment of reinforcements and replacement of Suwayda’s governor did not deter demonstrators. “People’s participation, their determination to participate, increased,” she said. Damascus’ insinuation of force “pushed people who had stopped coming out to return to the square.”

“We are proving the peacefulness of our movement, how right it is,” the activist added. “Despite cases of defamation and abuse on social media, women have not stopped being out in the squares to demand their dignity and their rights.”

Still, with the regime’s security and administrative changes, Suwayda’s movement is entering a new phase. “It is not possible to find a clear vision for its future,” Subaie said, other than that “this movement will not stop or end easily, after 10 months during which it has remained peaceful.”

Despite the strength of the movement, “the regional and international political course is what will play a major role in the future of the movement,” Subaie added. “The movement could end with the desired demands being achieved, or with repression, or the regime could bet on people tiring or becoming distracted by other problems.”

This report was produced as part of Syria Direct’s Sawtna Training Program for women journalists across areas of control in Syria. It was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.