Syrian refugees who left quake-affected Turkey for Syria face a hard restart

IDLIB, ISTANBUL — More than 12 years ago, Mira al-Muhammad […]

4 June 2023

IDLIB, ISTANBUL — More than 12 years ago, Mira al-Muhammad and her husband began to build a life in southern Turkey after fleeing her hometown, the Syrian city of Hama, as newlyweds. In Hatay, they lived, worked and had four children.

Four months ago, it all came crashing down.

On February 6, a devastating earthquake struck both Syria and Turkey, leaving a trail of destruction and loss in its wake. The 7.6-magnitude earthquake killed more than 52,000 people across both countries. In Turkey, more than 4,000 Syrian refugees were killed. Among them were al-Muhammad’s husband and two-year-old son, who died when the building the family lived in collapsed.

“My life was totally destroyed after the earthquake,” Mira, 33, told Syria Direct from a displacement camp near the Idlib province city of Harem.

With nothing left in Turkey, Mira returned to Syria two weeks after the earthquake with her three surviving daughters, joining her parents in a camp in Harem, where hundreds of internally displaced families live. “Our lives were upended. The quality of life for my children has become unbearable, something I never imagined we would endure,” Mira said.

Following the earthquake, Turkish authorities announced that “Syrians under temporary protection registered and residing in the earthquake affected provinces (Kahramanmaraş, Hatay, Gaziantep, Malatya, Kilis, Osmaniye, Diyarbakir, Adana, Adıyaman, Sanliurfa) can return to Syria temporarily,” but would have to return to Turkey before September 15, 2023 in order to keep their temporary protection status. Since then, more than 56,000 Syrians have returned to opposition-held northwestern Syria, according to Turkish Minister of National Defense Hulusi Akar.

Taha al-Ghazi, a Syrian refugee rights activist in Turkey, argued that some of the statements made by Defense Minister Akar about returnees referred to them as people who “voluntarily” chose to go back to Syria, as if it was a one-way trip. “Some of these refugees who could financially start a new life in Turkey already came back, before it’s too late for them to come back again,” he told Syria Direct.

Mira wants to return to Turkey, but acknowledges the immense difficulty of going back. Losing her home and husband, who worked to support the family, makes the prospect of return daunting. “I truly wish to go back, but I am uncertain whether I will be able to,” she said.

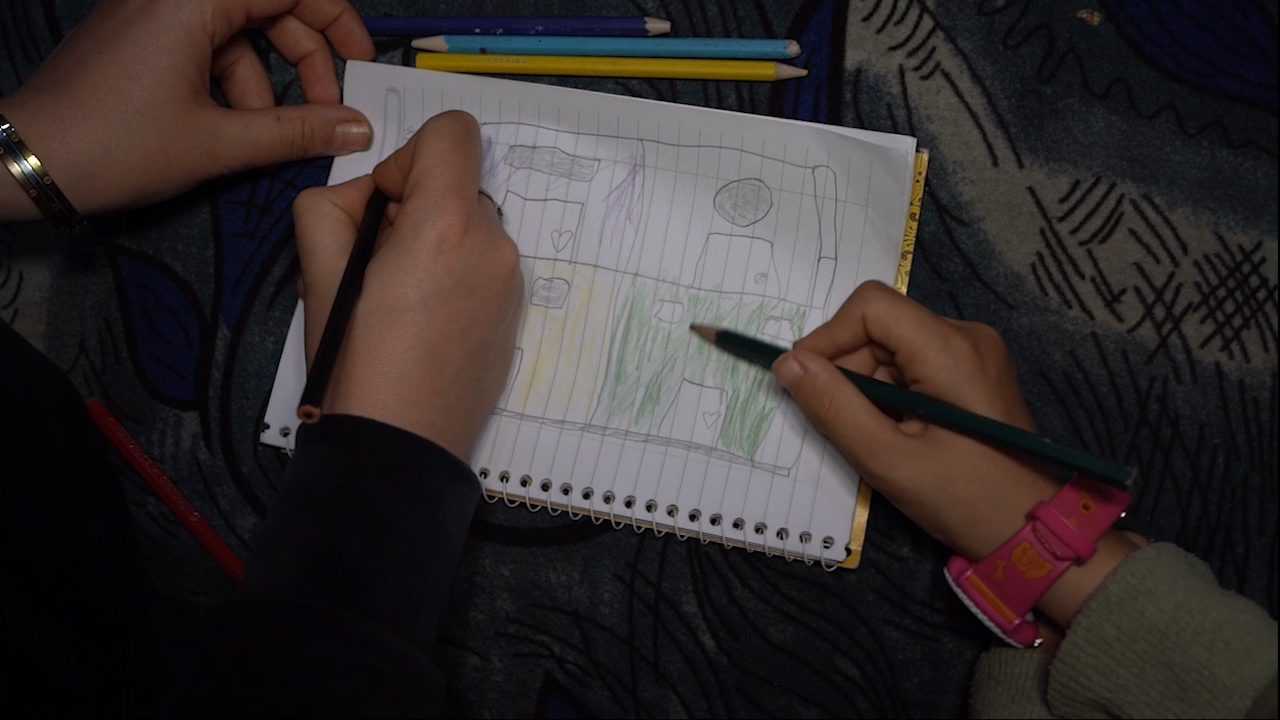

For Mira’s daughters, adjusting to life in Syria has been difficult. All of them were born and raised in Turkey, and her daughters attended Turkish schools. In Harem, her three daughters had to begin school all over again due to their limited proficiency in Arabic. “My daughters face bullying at school due to their language barrier as they speak Turkish, and because they are considered too old for their current grade level,” she explained.

In Idlib, Mira and her daughters share a tent with her parents and three adult sisters. Her father runs a small market in the camp, which is their main source of support. The family also relies on humanitarian aid provided by international organizations.

According to UNOCHA, 2.9 million Syrians are internally displaced, 1.9 million of whom live in displacement camps in northwestern Syria in harsh humanitarian circumstances. The already dire humanitarian circumstances in the area were further exacerbated by the impact of the February earthquake, which displaced at least 53,000 additional families.

Since returning to Syria, Mira says that she has felt dead inside. “We were not wealthy in Hatay, but we were satisfied. We had a home and a life. Now, we have lost everything,” she said.

Her eldest daughter Maya, 11, is not happy with their new home in the camp. Speaking in fluent Turkish, she recalled her memories with old friends in Turkey, the school she attended and her younger brother who was killed in the earthquake. “Here, there is no electricity, no good schools, no friends, nothing,” she said.

Maya al-Muhammad, 11, looks out the window of her grandfather’s residence in a displacement camp in Harem, Idlib. Born and raised in Turkey, transitioning to life in northwestern Syria after the February 6, 2023 earthquakes has been a challenge. With limited Arabic reading and writing skills, she is starting school again from the first grade, 7/5/2023 (Ali al-Dalati/Syria Direct)

‘No good future’

Syrians who remained in Turkey after the earthquake also face an uncertain future. The country’s 3.6 million Syrian refugees became a wedge issue in the runup to the country’s recent presidential elections, which saw President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan reelected in a runoff vote on May 28.

His rival, opposition leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, had made deporting Syrians a central electoral promise, falsely inflating their number and vowing to send 10 million refugees back if elected. In the days before the runoff, Kılıçdaroğlu’s supporters plastered streets with signs reading “Syrians will go.”

Erdoğan’s win came as a partial relief for Syrians in Turkey, but he too has promised to voluntarily return one million refugees back to a “safe zone” in areas of northern Syria controlled by Turkish-backed forces. Human Rights Watch has documented hundreds of cases of Syrians being forcibly returned to Syria by Turkish authorities.

Anti-refugee sentiment is rising in Turkey, where one recent United Nations (UN) study found that 82 percent of citizens believe Syrians should be sent back to their country. In early May, during the run-up to the elections, Al Jazeera correspondent Rokaya Çelik was attacked by supporters of the nationalist Good Party during her live coverage for “speaking Arabic” in Turkey.

Turkey’s economy is in steep decline, with soaring inflation. The cost of living is rising, particularly in areas such as home rentals and basic goods, financially burdening the country’s population—Turks and Syrians alike. These economic challenges contribute to a growing sense of frustration and reduced tolerance among some Turkish citizens towards the presence of millions of refugees.

Mira misses her life in Turkey, but loves Syria and would like to stay surrounded by her parents and siblings. Still, a better future for her children is her ultimate goal. “Syria is my home country, nothing will change this fact, but I’m sure that there is no good future for my daughters here,” she said. “I pray we can leave for a better place soon.”