Syrians in exile respond to travel vloggers touring Syria: ‘They are just some kids playing in the blood of Syrians’

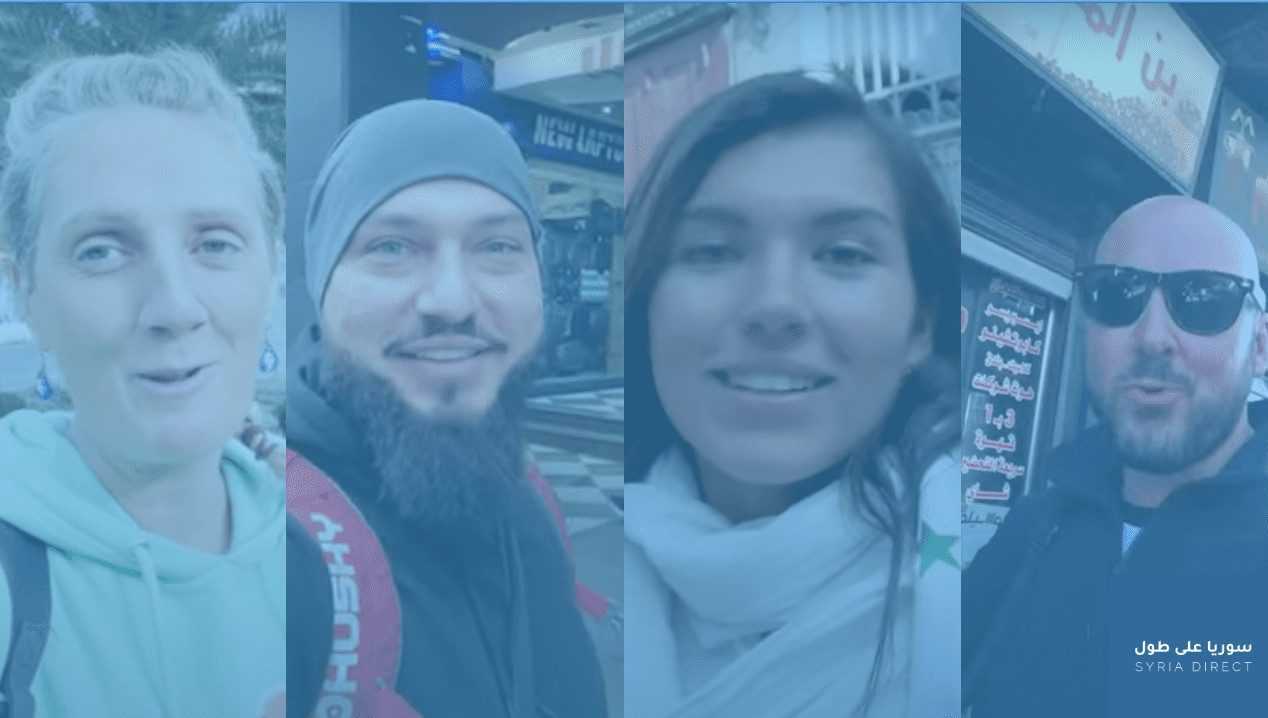

Refugees who cannot return to Syria react to travel vloggers who claim to be apolitical and portray Syria as safe.

16 August 2022

BEIRUT – Daham Alassad was born in a house 200 meters away from the ruins of Palmyra in Syria’s Homs province. Like his father and grandfather before him, he grew up hearing stories of the ancient city and worked in the Syrian desert oasis as a tour guide, telling visitors about its marvels. After the 2011 uprising against President Bashar al-Assad turned into a war, Daham, like 6.8 million Syrians, fled his homeland. He has not been able to set foot in Syria since—unlike an increasing number of foreign tourists and vloggers.

Three years ago, Daham came across a YouTube video that shook him: a Polish-American woman visiting Palmyra. “Why can these vloggers go to Palmyra, and I can’t take my kids there? Why do I have to tell my children stories about Palmyra from books, and I can’t just go there and tell them the stories like I used to with tourists before the war? It’s depressing,” said Daham, who now lives in Europe and works as a documentary filmmaker.

The same Syrian government that has forcibly disappeared 86,792 people has offered tourist visas—at a cost between $70-160—since 2018. Recently, after the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions, more travel vloggers are visiting cities under government control such as Damascus, Homs, Aleppo and Palmyra.

Many vloggers, who mispronounce “shukran” or “marhaba” (thanks and hello in Arabic) when interacting with locals, seem to have only minimal knowledge of Syria’s recent history. Some express pride at presenting an image of Syria “the media won’t show you,” seemingly unbothered by the fact that they can get visas while most journalists cannot.

In videos with titles such as “The Syria Media Won’t Show you” or “Syria: Everything FREE for Tourists,” visitors with millions of online followers marvel at Syrian food, emphasize the hospitality of locals and explain how safe Syria is. When visiting war-torn areas, a sad instrumental tune sometimes plays in the background as a Syrian guide explains that “militants” or “terrorists” are solely responsible for the destruction. This narrative omits the fact that Syrian regime forces and Iranian militias are responsible for 87 percent of the 228,893 civilian deaths, according to the Syrian Network of Human Rights, as well as extensive damage to civilian infrastructure.

Palmyra, Daham’s home, is a popular stop on foreigners’ tours of Syria. Some vloggers visiting bullet-ridden-Palmyra seem appalled when they step into the ancient theater that became the backdrop of executions filmed by the Islamic State (IS). That same theater was Daham’s favorite spot in Palmyra. “I used to hear opera groups coming from around the world when I was a kid. I loved music,” he said.

Daham fled Syria in 2012, and the rest of his family fled in 2015 when IS took control of Palmyra. While there, IS destroyed and defaced parts of the ancient city. In 2017, the Syrian army retook control. “There’s no one in Palmyra now, even if we want to go back, we are not allowed,” Daham said. Most Palmyra residents have not been allowed back due to the presence of militia groups, he added. “In my home there’s an Afghan militia, and in the family house there’s people from Hezbollah. The vloggers didn’t mention this in the videos,” he said.

Some of the militiamen in the pro-Assad camp come from Iran, Afghanistan, Iraq or Lebanon. State-approved guides tend to omit these kinds of details, feeding vloggers—and by extension their viewers—an easy binary narrative: The Syrian government fought extremist groups. This narrative erases the thousands who took to the streets demanding freedom in the early days of revolution and were met with tanks, as well as the complexities of the war that followed.

“Some of these videos in Damascus or Palmyra show places where my friends have been killed and arrested, where police shot people at demonstrations. These vloggers are walking in places where there are bodies under there. How do they feel?” Daham wondered.

“These vloggers are just some kids playing in the blood of Syrians.”

‘I feel disgusted’

In one video posted early this year, an Azerbaijani TikToker films himself in a destroyed area in Homs and blames the destruction on the Free Syrian Army, a group founded in 2011 by defected Syrian military officers. As human rights researcher Sophie Fullerton pointed out in a tweet responding to the video, this influencer neglects to mention the Syrian army’s role in shelling and bombing Homs.

On his regime sponsored trip, vlogger Davud “educates” his followers on the Syrian war by claiming the FSA was responsible for destroying Homs.He conveniently leaves out that the regime has dropped 83,000 barrel bombs,that deliberately targeted civilian infrastructure. https://t.co/XL3gGNhZte pic.twitter.com/ysY7aPR5Yg

— Sophie Fullerton (@florida_sophia) January 2, 2022

Abdalla Hussein spent six weeks under heavy regime bombardment in Homs, until he fled his hometown in 2012. “I am from Homs, a city destroyed and shelled by the Syrian regime. Our houses were robbed and burnt by their shabiha [pro-Assad paramilitaries],” Abdalla said from Italy, where he was granted political asylum. “What are these vloggers talking about? They don’t have a clue about the context, about the revolution, the exile, the destruction of Syrian cities, ” he said.

“What do these YouTubers know about the Houla massacre, the Queiq massacre in Aleppo, about journalists Marie Colvin and Remi Ochlik killed under shelling in Baba Amr [in Homs]? What do they know about activists like Razan Zeitouneh abducted by Jaish al-Islam, or the Italian priest Paolo Dall’Oglio disappeared by Daesh?” Abdalla asked.

“There’s no respect for the dignity of the Syrians killed, those in prison, those in the camps in Lebanon, Jordan or Turkey,” he said. “It is disgusting to see these foreigners going to Syria and saying that Syria is a nice country and all is good, while me, a Syrian watching this video, I can’t go back to my country.”

“I feel disgusted when I see these videos,” he summed up.

Noura Ghazi, a Damascene living in exile in France, has mixed feelings when watching travel videos from Syria. “In a normal situation, as a Syrian I should be happy that people are going to Syria and enjoying it, but the situation is not normal. Half of Syria’s population is displaced, and half of those displaced want to go back and can’t, including me,” she said.

Noura is a prominent human rights lawyer fighting for the rights of detainees and the families of Syria’s disappeared. Her husband, activist Bassel Khartabil, was forcibly disappeared in 2012 and executed in a Syrian state prison in 2015. “I can’t go back to Syria because I will be arrested,” she said.

Before fleeing Syria in 2018, Noura used to pamper her niece and nephew, buying them presents every time she traveled. “My niece once asked me, ‘When are you coming back and what will you bring us?’” she remembers. Noura never came back. “This question is still killing me. I still have nightmares about this question,” she said.

“I feel deeply sad because I am not able to go to my country and enjoy the things that these YouTubers are enjoying,” she added.

Whitewashing and the passive voice

Vloggers visiting Syria master the art of using passive verbs when confronted with the traces of war: Neighborhoods are reduced to rubble, cities are destroyed, war happens. If they ask their guide who bombed a particular building, the guide will reply militants, extremists or radicals.

“They want to show only two parties, ISIS and the Syrian regime, no one mentions the secular street movement,” Noura said, adding that “for generations, people were fighting peacefully against this regime.”

Some vloggers seem less knowledgeable about Syria than others. In a 2022 video, one asks his guide when the Syrian war started and was surprised that every shop had a portrait of Bashar al-Assad. “Is that because they like him? I will ask Rami (his guide),” he said.

Another influencer, after being told by his guide that the problem in Syria was foreign interference like Turkey’s support for armed anti-Assad groups, he parrots back to his audience: “You hear that? Foreign troops, get out!” This vlogger seemed unaware of Iranian, Russian or Lebanese presence in the pro-Assad camp.

“Some could be naïve, some probably have an agenda in marketing the Syrian government as trying to protect Syria from terrorist rebels,” Noura said. “If these vloggers have a link with the Syrian regime I don’t have anything to say to them, because the same regime displaced almost 12 million, killed almost one million, and disappeared and arrested hundreds of thousands,” she added.

For Abdalla, whether these vloggers are naïve or not is besides the point. “What comes out of these videos benefits the regime. Maybe the vloggers don’t know the consequences, but regardless, they are doing a great service,” he said. “The Syrian regime is criminal, but it is clever. They are not dummies, they want to show that the country is okay, refugees should return, Assad controls the country, the rest are all terrorists and that the international community should give Damascus money to rebuild the country.”

Daham rebuked the idea that these vloggers are apolitical, as some claim to be. “They can’t be apolitical when they go to a war zone, when the war hasn’t ended and journalists are not allowed to go, why are you [vlogger] allowed, and I am not allowed?” he asked.

“They say they are going to Syria for fun, you can’t have fun with people’s blood. There is a dictator that destroyed the country, it should be a war crime to whitewash these kinds of things,” Daham said. “Can you imagine a guy visiting Germany in the Second World War while Hitler was still there?”

Daham said he understood locals in Syria need the money that tourists can bring, “but before they deserve tourists or their money to be back, we [displaced Syrians] deserve to be back without this dictator.”

It’s not the bombs, it’s the dungeons

All vloggers emphasize, some with surprise, how safe Syria is. In an early 2022 video, one says he will “change your opinion about Syria” by taking a night stroll alone through the streets of Damascus.

For Noura, Abdalla and Daham, this narrative is both false and dangerous. “Syria is safe for this foreigner YouTuber who hangs out in Syria without understanding anything, safe for the European extreme right groups that visit Assad or for Jackie Chan to shoot a movie in a destroyed place without respect for the Syrians who lived there. But it is not safe for me or my family,” said Abdalla, who fears these types of videos may push more people in the West to call for refugees to return.

Daham sees travel videos from Syria as a “gift” for the “right wing pushing for normalization with Damascus and sending refugees back.” Three years ago, he released a short film about a Syrian refugee family at risk of being kicked out of Denmark on the grounds that Damascus is safe for return.

Vloggers seem to equate safety to the fact that Assad controls 80 percent of the country, and that bombs are not falling as they did in the worst years of the war. In Noura’s point of view, it was not the shelling, but the security forces that many Syrians fear: “the most important reason that pushed Syrians to leave is that they would be arrested,” she said.

Travelling with security clearance from one of the security branches that have tortured and executed thousands, vloggers often reflect on the generosity of Syrians after being offered free sweets in the street—the same streets that thousands of Syrians can’t set foot in.

Noura misses the sea of Latakia and Tartous, the villages around the Barada river in the Damascus countryside, and Bab Touma and Bab Sharqi in central Damascus. In Paris, she sometimes feels nostalgic when she walks by an old building designed in a similar fashion to the ones in Damascus built under French occupation in the early 20th century. “If I had a guarantee that I would not be arrested, I would pack and go back immediately,” Noura said. “I’m just trying to adapt to the concept that probably I will never go back unless a miracle happens.”

For Abdalla, his special place in Homs was the football stadium. “Me and my friends would go two hours before the match, we used to sing, be happy. After the match it was so late there were no buses left, so we had to walk, and all the streets were full of happy people singing in the streets,” he recalled. “That’s a sweet memory.” He says maybe in ten years, if Assad is not in power, he could go back.

Daham gave up on the idea of going back to Syria three years into displacement. “Maybe it’s because of our Bedouin blood,” he said, half joking. After three generations, he is the last tour guide in his family.