Turkey’s housing projects in northwestern Syria: An expanding, contested policy

Why is Turkey interested in building housing in northern Syria? Who funds and implements these projects? And why are some human rights actors concerned about Ankara’s activities?

8 July 2022

PARIS —In June 2022, while paying a visit to Turkish-controlled areas of northwestern Syria, Turkey’s Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu announced 240,000 housing units would soon be built in the region to serve the needs of internally displaced Syrians and returning refugees.

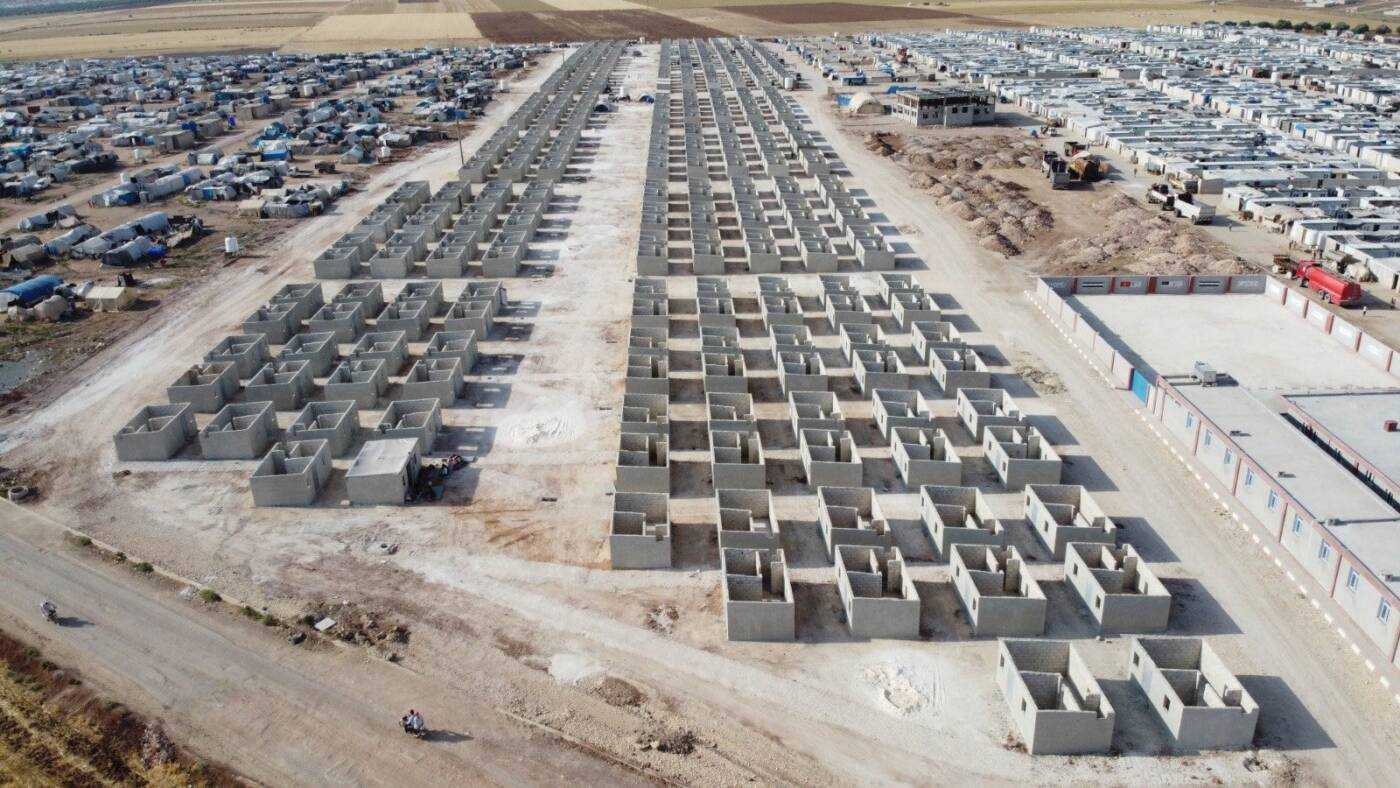

Soylu’s statement signaled an ambitious acceleration of Turkey’s house-building policy in Syria. Over the past three years, Turkish NGOs and development agencies built tens of thousands of cinder block residences in northwestern Syria, with the stated aim to stabilize the humanitarian situation and incentivize Syrians to remain.

But while Turkish construction in northern Syria is expanding—in response to domestic political concerns and stated humanitarian objectives—it is also being criticized by several human rights organizations, who question its legality. So why is Turkey building residences in northern Syria? Who funds these projects? And whose rights might be violated in the process?

Why is Turkey building houses in northern Syria?

Three cross-border military offensives allowed Turkey to seize large swathes of northern Syria in recent years. The first, Operation Euphrates Shield, targeted the Islamic State in rural Aleppo in 2016. The following two operations, Olive Branch in 2018 and Peace Spring in 2019, were directed against the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in northern Syria, a formation that includes the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG). The YPG, and its civil wing the Democratic Union Party (PYD), has ties to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Ankara’s historic enemy.

Turkey says the goal of these military operations is to turn the north of Syria into a “security strip” by pushing Syrian Kurdish military groups away from its southern border. This “buffer” is mostly controlled by the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA)—a coalition of opposition militias—and ruled by local authorities that provide basic services for the civilian population, in cooperation with Turkey’s Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD), which coordinates Turkish relief.

While Ankara’s military involvement in northern Syria stems from national security concerns, its humanitarian involvement largely stems from a desire to “stabilize” the region amid rising concerns about the growing number of vulnerable Syrians amassed at its border and continued border-crossing attempts as conditions worsen in Syria. Turkey currently hosts around 3.6 million Syrian refugees.

Building housing is an integral part of this “stabilization” strategy: In May 2022, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced that more than 57,000 Turkish-funded homes had been built in Idlib province since 2019, out of an initial plan to build 77,000. Turkish authorities later unveiled plans to build an additional 240,000 houses across thirteen localities in northwestern Syria, including Jarablus, Al-Bab, Afrin, Idlib, Tal Abyad and Ras Al-Ayn.

Who are Turkish housing projects for?

Until now, house-building projects in northwestern Syria have been geared towards the 2.8 million internally displaced Syrians in opposition-held Idlib and Aleppo provinces. Their stated aim is to improve displaced people’s living conditions by transferring thousands of people living in informal camps to concrete housing.

The recently announced construction of 240,000 additional units greatly expands the reach of Turkey’s policy. The move has been associated with a broader plan to ‘“voluntarily” repatriate more than one million Syrians in the coming years, most likely to Turkish-controlled areas of Syria.

[irp posts=”44487″ name=”Turkey eyes voluntary return for 1 million Syrian refugees, but ‘the problem is bigger than providing housing’”]The latest push to return refugees comes as Turkish politicians scramble to score points ahead of Turkey’s upcoming general elections in June 2023. Recent months have seen skyrocketing hate speech and xenophobia against Syrians in Turkey, who are increasingly—and baselessly—blamed for the country’s spiralling economic crisis.

Why is this construction policy contested?

Proponents of Turkey’s construction policy say building housing is “a critical step” to stabilize the living conditions of displaced Syrians and refugees. In a May 2022 analysis for the Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP), Syrian researcher Ammar Al-Musarea highlighted the plight of northwest Syria’s displaced residents, some of whom have been living in tents for a decade. For them, Musarea argues, emergency stop-gap solutions provided by humanitarian actors are no longer enough: Syrians need permanent housing, return plans and stable access to services such as health and education.

[irp posts=”39297″ name=”Still under water: Fix-gap relief isn’t enough for Idlib’s IDPs facing annual flooding”]But Ankara’s latest announcement triggered concerns among human right organizations, which documented the forcible deportation of tens of thousands of Syrians from Turkey between 2019 and 2021. They fear Turkey’s residential projects will justify further forced returns.

In some parts of northwestern Syria, observers worry that Turkey’s mass relocation strategy will dangerously alter the region’s demographic balance and cement the dispossession of Kurdish and Yazidi communities who have already been subjected to “systemic” looting and property seizures by Turkish-backed factions.

“The Turkish plan for repatriating one million Syrian refugees is predicated on settling them in Turkish-occupied areas in northern Syria. Many refugees did not originally call these Syrian provinces home,” local human rights monitors wrote in a statement submitted to the UN General Assembly in May. “Instead, many of these areas have historically housed majority Kurdish communities who have themselves been displaced.”

Aggravating these concerns is the fact that a significant share of existing housing units—built under the guise of humanitarian aid—have benefitted military factions and local elites rather than the civilian population as a whole.

The human rights watchdog Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ), in a report released in June, likened Turkey’s construction policy to “demographic engineering.” In Afrin, a region historically home to a large Kurdish population, extensive settlement-building has taken place in areas historically inhabited by Kurds who fled the region en masse fearing persecution from Turkish-backed groups following Operation Olive Branch in January 2018. According to STJ, slots in these Turkish-built settlements are allocated through opaque processes that favor SNA fighters and their families, who represent up to 75 percent of final beneficiaries.

Who funds and implements these projects?

Thousands of houses for displaced people were built in recent years by various Turkish and Syrian relief organizations, with coordination from AFAD.

Organizations that built some of these settlements include the Turkey based Ozgur-der, Fetih Association, Ihsan for Relief and Development and the Humanitarian Relief Foundation (IHH), which has built over 25,000 units in northern Syria since 2019. The same organization also allegedly funded part of the settlements being built in Afrin, according to STJ.

Although there is no openly accessible data on these projects and donors, some have apparently been funded by AFAD, and others by private donors from the region, generally faith-based Muslim charities like the Kuwait-based Rahma International Society or the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB), a German-based organization with strong ties to the Turkish state. Syria Direct contacted AFAD for information on its housing projects, but did not receive a response.

Meanwhile, in an interview with Turkish channel TGRT Haber on May 5, Soylu underscored that the upcoming construction of 240,000 homes would not be taken from Turkish pockets and be “fully funded” by “international humanitarian organizations,” without providing more details.

Are these settlements legal?

The legality of Turkish-led construction efforts in northern Syria has been questioned at two levels: whether they comply with Syrian property laws, and with international law governing the obligations of an occupying power (in this case Turkey) in territories under its control.

The first question illustrates the difficulty of carrying out any permanent construction and infrastructure work in northwestern Syria, where “widespread displacement and [a] legal vacuum make it very difficult to verify ownership and claims, and legal proof of registered land ownership is often not available,” according to a humanitarian manual released in 2020.

Since the start of the war, millions of Syrians have been displaced (mostly to the northwest), their properties destroyed and occupied, and property laws amended in various parts of the countries to advance the interests of local “winners.” Syria no longer has a transparent, unified and unanimously recognized legal system to record and guarantee property transfers, and the legitimacy of “local authorities” that arose in different parts of the country is contested.

Being committed to “do no harm” to the society in which they work, NGOs and aid agencies—in principle—seek to ensure the projects they implement do not cement dynamics of dispossession and forced displacement. Guided by this principle, many international NGOs have shied away from building houses and carrying out structural improvements to informal camps built on land where ownership cannot be verified. Large institutional donors have also refrained from funding large-scale construction in northwestern Syria.

Turkish-backed construction projects are marred by the same concerns. According to the specialized economic publication The Syria Report, in many cases the right of foreign NGOs to buy and own the land on which they are building is unclear. To get around these issues, projects are often implemented on loaned public and endowment land (properties which are neither private nor public, but are set aside permanently for charitable purposes, known as awqaf under Islamic law). Beneficiaries typically receive the right to use the property for five to ten years, or a deed to the property itself, but do not own the land.

While this system complies with Syrian property law, it does not entirely resolve questions surrounding the origin of the “public” land, which could belong to dispossessed or absentee owners, nor the local authorities’ legitimacy to attribute it.

The second question points to the responsibility of Turkey, as an “occupying power” in parts of northern Syria, to protect the rights of the local population in accordance with the Fourth Geneva Convention. In principle, the Turkish state can be held responsible for the international law violations committed in the territory it controls—including arbitrary property seizures, looting, and policies aimed at displacing certain groups. Settlements that are founded on or contribute to such violations, as STJ argues is the case in Afrin, are therefore also illegal.