Will the Caesar Act bolster Damascus’ popular support?

Damascus has exploited the Caesar Act and accompanying sanctions to offset blame for its economic shortcomings.

17 June 2020

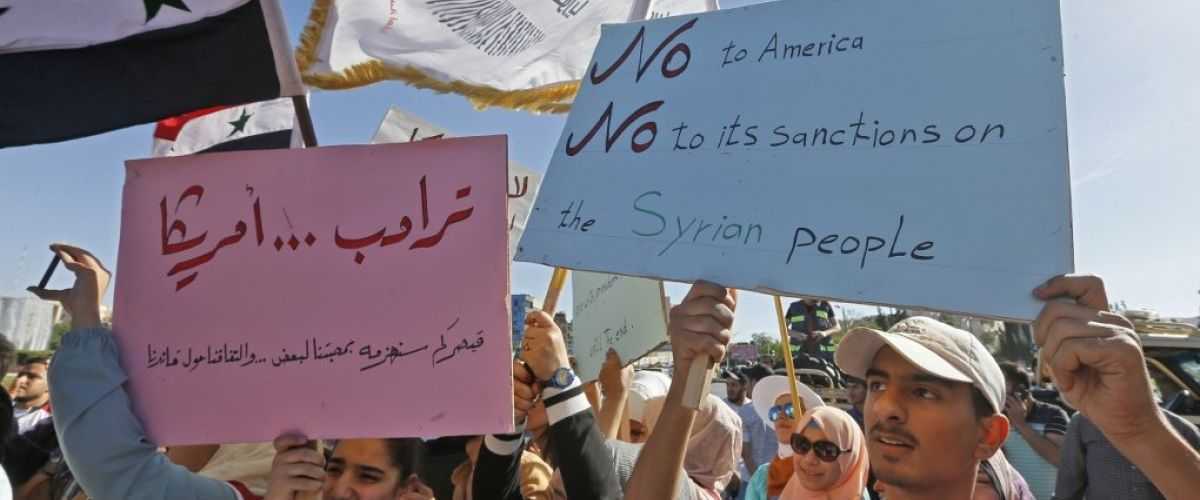

Syrians participate in a march in support of Bashar al-Assad and against the US Caesar Act in the Ummayad Square in Damascus, 11/06/2020 (AFP)

AMMAN — In a recent commercial circulating on official Syrian television, Syrian students all over the world raise handmade signs and solemnly urge the international community to lift sanctions against Syria.

These students, organized by the mukhabarat (state intelligence service)-affiliated National Union of Syrian Students, are part of a media campaign led by pro-regime media, which has escalated into a fever pitch in advance of the activation of the United States’s Caesar Syrian Civilian Protection Act today.

The Caesar Act, signed into law on December 20, 2019, gives the US President the ability to impose sanctions on any individual or entity of any nationality which “supports or engages in a significant transaction” with the Assad regime. In effect, the law ensures the continued diplomatic isolation of Damascus and dashes regime hopes of incoming reconstruction funds following its defeat of opposition forces everywhere but Idlib province.

Syria, however, is facing a vastly different set of conditions on the day of the new sanctions’ application than it was when the act was passed just six months ago. In the last two months, the economy has entered into a virtual death spiral, with a currency whose decline seems to have no bottom and rising prices which seem to have no ceiling.

In response to the worsening economic conditions, protesters have taken to the streets in the relatively quiescent Druze-majority Suwayda province, calling for the fall of the Assad regime. Security forces have arrested participants and organizers of the demonstrations, but have thus far not used the same violence which they used to crush protests in 2011.

For its part, the regime has blamed the economic crisis primarily on sanctions, in addition to what it has dubbed as corrupt traders taking advantage of the situation. Instead of addressing the grievances of the protesters in Suwayda, Damascus has ignored them and recast the demonstrations as marches against sanctions.

Targeted sanctions with broad effects

Despite the Caesar Act containing exceptions for food, medicine and other essential imports, many in Syria are either unaware of these exemptions or fear that the sanctions will indirectly increase the cost of such staples regardless.

The law explicitly targets “military issues, rather than food and medicine,” Khalid al-Terkawi, an economics researcher at the Turkey-based Jisoor Center for Studies, told Syria Direct. Further, the act and its resulting sanctions “can be reversed if the regime adheres to its provisions, such as halting bombing [of civilians] and releasing detainees, in addition to other demands,” al-Terkawi added.

Other analysts, however, have described the demands that the regime needs to fulfill to lift sanctions as a “high bar,” and previous calls for behavioral changes from the regime have fallen on deaf ears, even when accompanied by international sanctions.

In general, doubt has been cast on the efficacy of economic sanctions in changing the behavior of states.

In a seminal paper on the subject, “Why economic sanctions do not work,” Dartmouth professor Robert Pape describes how even under sanctions, “most modern states resist external pressure,” as “even when the ruling elite is unpopular, they can still often protect themselves and their supporters by shifting the economic burden of sanctions onto opponents or disenfranchised groups.”

In addition, given that the law calls for accountability for crimes committed over the last nine years, it’s likely that many in the regime or close to it view the implementation of the reforms required to lift the Caesar Act as existential, since many of them are complicit in war crimes.

Thus, barring some significant change in behavior from Damascus, the sanctions are likely here to stay.

The short-term result will be a halt in reconstruction aid, both from the EU and neighboring countries. The sanctions “will push Arab business people not to enter into partnerships with Damascus, and to halt investments in Syria,” al-Terkawi said, citing Jordanian and Emirati investors who wanted to invest in Syria but decided not to do so after American warnings.

While it’s probable that these business partnerships would have gone through Syrian elites rather than small-time traders, the lack of incoming capital still means that “all Syrians will be affected by the [act] in practice, especially since the regime is unable to provide anything but more restrictions,” al-Terkawi said.

A pressure point or a convenient out?

Though the current economic crisis has many factors behind it—including systemic factors like rampant corruption, infrastructural collapse and a population devastated from nearly a decade of war—it seems Damascus has found a convenient scapegoat for its economic woes: sanctions.

Damascus has already sought to shift the focus from protests in Suwayda against the regime to counter-rallies organized by pro-regime figures in Daraa and Latakia province against the Caesar Act and the “coercive economic measures imposed on the Syrian people,” according to the Syrian government news agency, SANA.

One of the organizers of the protests explained that they were displaying the “unity of the Syrians and their standing by their leadership and their army in the face of all those who are trying to target their country.”

The organizer’s statements echoed the sentiments of Buthaina Shaaban, Bashar al-Assad’s political and media advisor, who urged Syrians to be “steadfast,” explaining that Syria as a whole “has no choice but patience and steadfastness,” promising that it will all “pay off soon.”

Given the somewhat complex nature of the sanctions that have been placed on Damascus, it’s not impossible to generalize the impact of the sanctions to include all Syrian people and exaggerate their effects on the Syrian economy, even though the law only targets those working with or assisting the regime.

Besides its domestic messaging, Damascus’ rhetoric against sanctions has an international audience and feeds into a long-standing narrative of the regime being a victim of an international, mostly-western led, imperialist campaign which has won it support abroad. To many, a new round of US sanctions is merely validation for this theory.

Bashar al-Jaafari, Syria’s representative to the UN, submitted a formal complaint to the UN on June 16, denouncing the Caesar Act sanctions as “terrorism” and foreign interference that seeks to fulfill Israeli policy goals.

Such messaging has won Damascus allies with western leftists. For example, in September 2019, a group of leftist Americans, led by the political activist group, US Labor Against War, visited Damascus in order to take part in the 3rd International Trade Union Forum and denounced sanctions as part of their trip there.

Regardless of messaging coming out of Damascus, the reality is that Syria is facing a massive economic crisis that has the potential to evolve into a famine. According to a March 2019 UNHCR report, 83% of Syrians live in poverty, a number that has surely gone up since then.

The regime has weaponized humanitarian aid in the past against its opposition, punishing those who stood against it by excluding them from humanitarian aid distribution. In fact, “the regime is the one that prevents aid from entering through the Iraqi and Turkish crossings into the northeast and northwest of Syria, restricting its passage through its areas of control and supervising its distribution after stealing a large part of it,” Ayman Abdel Nour, the director of Syrian Christians for Peace, told Syria Direct.

All of this points to the fact that the regime “does not care if the poverty rate reaches 100% or if there is a famine,” according to Dr. Radwan Ziadeh, the executive director of the Syrian Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Washington, D.C., told Syria Direct.

Whether or not Syrians will buy the explanation offered by Damascus as to why they cannot put food on the table remains to be seen. However, as Ziadeh puts it, “in the end, [Syrians] need to feed themselves and their families, and rhetoric and slogans will not satisfy them.”

This article reflects minor changes made at 18/06/2020 at 10:26 am.