With all eyes on Lebanon’s south, number of Syrians leaving from northern shores spikes

Intolerable conditions in Lebanon are pushing increasing numbers of Syrians to take to the sea. With all eyes on escalating violence in southern Lebanon, the number of Syrians leaving from the north over the past two months reached more than four times the number for the same period in 2022.

14 December 2023

BEIRUT, TRIPOLI — Smoking his way through a pack of cigarettes in a Beirut cafe, 22-year-old Salah Abrush calls his friend, Feras, who arrived in Germany in September. When he hangs up, Salah leans back in his chair. A hopeful smile stretches across his face. “They’ll help you in Germany,” he says, “not like here in Lebanon.”

Feras—who, like Salah, is Syrian—paid a trafficker $8,000 this past July to take him on a flight from Lebanon to Tunisia, followed by a 22-hour boat ride to Italy and finally a nearly month-long walk from Italy, through Switzerland, to Germany.

Six months later, Feras is settled in the western German city of Cologne, where he is waiting for his asylum application to be processed. Hearing about his success has left Salah eager to attempt a similar journey himself.

Salah says his life in Lebanon has become unbearable. He was a child when his family came here from Aleppo in 2009, before the war, and stayed as conditions in Syria worsened. After 2011, as 1.5 million Syrian refugees streamed into the country, his life in Lebanon grew increasingly difficult. Most of his family has returned to Syria, but he does not want to go back, fearing punishment for evading Syria’s mandatory military service. His options for what to do next are slim, and all are dangerous.

Salah Abrush checks his messages from his friend Feras at a cafe in Beirut, Lebanon 7/12/2023 (Hanna Davis/ Syria Direct)

“It’s getting more dangerous for Syrians in Lebanon. We are hated here,” Salah says. He reaches up to touch the top of his head, running his fingers over a large lump that has formed. On November 10, a group of armed Lebanese men approached Salah and demanded he give them his moped, he says. When he refused, one of them hit him with a large metal rod, cracking his skull and causing a brain hemorrhage that left him near death.

A picture of the injury provided to Syria Direct shows a large gash running across the top of Salah’s head. He was taken to the hospital, where doctors told him he should stay overnight. But the stay would cost $1,500 without insurance, so he checked himself out after a few hours, with no choice but to heal at home.

Violence against Syrian refugees in Lebanon is on the rise, stoked by provocative media campaigns organized by the country’s politicians, who blame Syrians for the country’s ongoing economic crisis. Meanwhile, the Lebanese army has been carrying out an unprecedented wave of arrests and deportations of Syrian refugees.

Salah never attempted to press charges for the attack. His residency papers are expired, and if he went to the police he felt he would “definitely” be deported to Syria—an outcome he was not willing to risk.

Just about a month before he was nearly killed, Salah and five Syrian coworkers were let go from their jobs at Spinneys, a supermarket in Beirut’s upscale Achrafieh neighborhood. Salah said he was told the supermarket was closing, but when he returned to pick up his salary, he found it open and running, just without Syrian staff.

Now, Salah is sure he will leave Lebanon. “I don’t have another option,” he says. “Here, I’m 100 percent sure I won’t have a future. I won’t have kids. I won’t marry. I can’t do anything.”

With attention south, more Syrians leave from the north

With pressure mounting on Syrian refugees—and all eyes on increasing violence between Hezbollah and Israel in the country’s south—increasing numbers of Syrians are attempting a dangerous passage by sea to Europe, departing from Lebanon’s northern shores.

The first two months after the start of the war in Gaza have seen significantly higher numbers of people departing by boat from Lebanon than the same period last year, according to verified figures UNHCR Lebanon spokesperson Lisa Abou Khaled provided to Syria Direct. The vast majority of those attempting to leave are Syrians.

In October 2023, UNHCR verified the departure of nine boats carrying 598 passengers. Seven of the vessels successfully reached the shores of Cyprus, Lebanon’s Mediterranean neighbor. In October 2022, there were only two confirmed boats, carrying 67 passengers, and none were bound for Cyprus.

In November, eight boats carrying 327 passengers left Lebanon. Three arrived successfully, while four were returned. By comparison, November 2022 saw only four boat movements, carrying 137 passengers, and one successful landing on Cyprus.

“When everyone was focused on Gaza, more boats were likely leaving Lebanon,” Ibrahim Jouhari, a migration researcher and co-author of a 2023 Friedrich Naumann Foundation (FNF) paper on irregular maritime maritime migration trends from Lebanon, told Syria Direct. “No one has the bandwidth to focus on this when the south [of Lebanon] is burning,” he said.

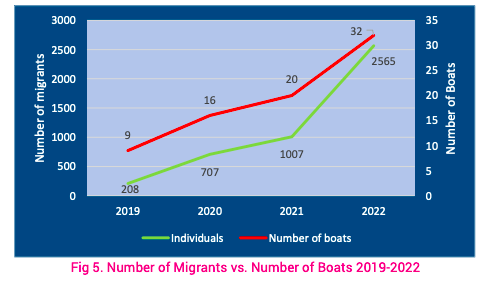

Before Lebanon’s economic crisis took hold in 2019, few people tried to migrate from Lebanon by sea. However, since then there has been a “significant yearly increase in the number of both ships and individuals attempting to migrate from Lebanon’s shores,” according to the FNF paper.

A graph shows rising numbers of migration boats leaving Lebanon from 2019-2022 (Jasmin Lilian Diab/Ibrahim Jouhari/Friedrich Naumann Foundation)

In late October as the war in Gaza—and escalation between Hezbollah and Israel in southern Lebanon—intensified, Cypriot authorities announced they were bracing for a larger influx of asylum seekers from Lebanon. The announcement came soon after they received boats from Lebanon carrying 458 Syrian passengers in the course of a single week.

The director of Caritas Cyprus, Elizabeth Kassinis, told Syria Direct that, according to figures announced by authorities, the number of Syrians arriving in Cyprus has “nearly doubled” since the start of October.

Cyprus authorities received 761 asylum applications submitted by Syrian nationals in October 2023, compared to just 370 the same month in 2022, according to figures UNHCR Cyprus sent to Syria Direct, collected and compiled by the Cypriot government. In November 2023, Cyprus authorities received 1,125 new Syrian asylum applications.

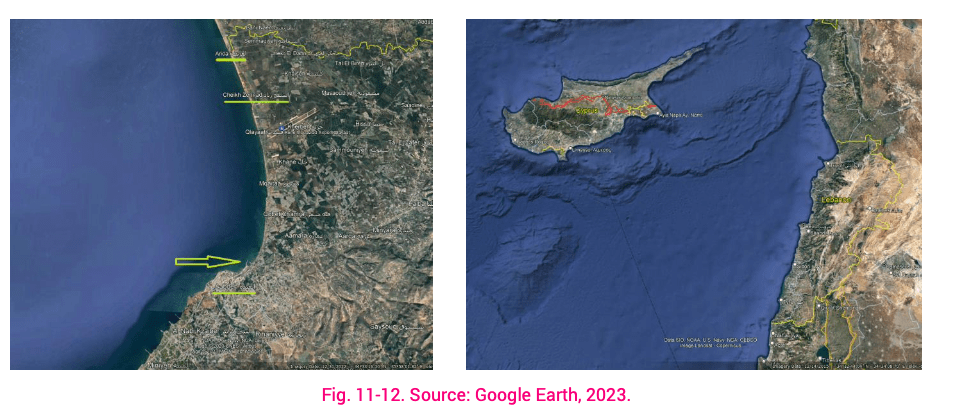

Common departure points from Lebanon include the Abdeh port in Tripoli governorate (indicated by the arrow in the map on the left), as well as Cheikh Zennad and Arida in Akkar governorate. The map on the right shows Cyprus and Lebanon (Jasmin Lilian Diab/Ibrahim Jouhari/Friedrich Naumann Foundation)

Perils of the sea

Ibrahim al-Aloun, a 23-year-old originally from Syria’s northwestern Idlib province, attempted to leave Lebanon by boat nearly a year ago. He, his wife Ghadia and their five-month-old son departed from Lebanon’s northern coast late last December, hoping to arrive in Italy and then head on to Germany, he told Syria Direct from Tripoli.

Ibrahim and his family were among 4,334 people who attempted to informally immigrate by boat from Lebanon’s shores in 2022—a 176 percent increase from the 1,570 people who made similar attempts in 2021. In 2023, the numbers remain high, with 3,158 passengers attempting to depart by boat as of November, according to UNHCR Lebanon.

“The continuous economic collapse is affecting Lebanese, Syrians and Palestinians,” Jouhari said. “The crackdown on Syrians has caused fear within their community, likely pushing more Syrians to seek passage by boat.”

The total number of Syrians arriving in Europe via Greece or Cyprus is up 40 percent in 2023, Jouhari added, according to his analysis of Frontex data through October. The figures do not indicate where they departed from, but he noted that most migrants taking this route leave from Lebanon or Syria. Given strict Russian patrols of Syria’s shores surrounding its naval base in Tartous, “all indications point towards departure from Lebanon’s northern shores,” Jouhari said.

Lebanon is “increasingly becoming a transit country,” he added.

Ibrahim and his family embarked on a different route last year, heading straight for Italy to avoid Cypriot migrant patrols. In 2020, Cyprus and Lebanon signed a migration deal allowing Cyprus to return migrants back to Lebanon. In August 2022 alone, Cyprus returned over 100 Syrian nationals who had arrived by boat, without screening them for legal protection.

Ibrahim paid an exorbitant $12,000 for the journey for himself, his wife, and young child, giving the money to a trafficker before they departed. They were supposed to leave in July, but the trip was pushed back to December 31, the winter storms bringing much rougher seas than in the summer months.

When Ibrahim and his family arrived at the port in Der Amar, about 10 kilometers north of Tripoli’s major port, it was “stormy and rainy” and the boat—promised to be a larger ship for the long journey—was a simple fisherman’s vessel.

“‘You either get in, or we will kill you,’” Ibrahim said the trafficker told him when he expressed doubts about wanting to board. Boats leaving from Lebanon are often too small, and ill-suited for long sea journeys.

Eight hours in, the boat began to sink, capsizing in the cold water and rough sea. Two months earlier, around 100 asylum seekers were killed in a similar incident, when their boat capsized after departing for Italy from Lebanon.

Ibrahim’s boat capsizes in the cold water and rough sea, 1/1/2023 (Lebanese Armed Forces/Amnesty International)

In April of the same year, 47 people were killed when, survivors said, a Lebanese navy boat struck their vessel en route to Cyprus, causing it to sink in what appeared to be the first fatal attempt to cross the 131 nautical miles (200 kilometers) between Tripoli and Cyprus.

Read more: Pushed toward death in the sea: A survivor’s account of the Tripoli shipwreck

When Ibrahim’s boat sank on January 1, a Syrian woman and child died. The other 232 people on board—Syrians, Lebanese and Palestinians—were rescued by the Lebanese navy.

But when the passengers on the boat realized they would be taken back to Lebanon, Ibrahim said, “they wanted to throw themselves into the sea.”

Deported to Syria

After barely surviving the sinking, Ibrahim, his wife and son were loaded onto trucks by the Lebanese army when they reached the shore—along with nearly 200 other Syrians who had also just been rescued—and taken across the border to Syria.

The army’s forced return of this group of Syrians, some of whom were registered with UNHCR, violated Lebanon’s non-refoulement obligations to not return anyone to countries where they face a risk of persecution or other serious human rights violations, Amnesty International reported at the time. It was far from the only forced return.

From the start of 2023 up until November 30, Lebanon has forcibly deported 761 Syrians and arbitrarily detained 1,027, most of whom were registered by UNHCR, according to numbers provided to Syria Direct by Mohammad Hasan, the executive director of the Access Center for Human Rights (ACHR), a human rights organization based in Beirut and Paris.

This is a marked increase from 2022, when just 159 Syrians were forcibly deported, and from 2021, when the army deported 59 Syrians. In October, ACHR documented three cases of forcible deportation and in November, 28 cases. Hasan noted that the true numbers could be higher than those reported.

Read more: 1,100 Syrian refugees arrested, 600 deported from Lebanon in unprecedented crackdown

The US government and European Union (EU) continue to fund the Lebanese army, seemingly with little pressure on Lebanon to stop deportations. On September 13, the US diverted $85 million in military aid from Egypt to Taiwan ($55 million) and Lebanon ($35 million) over Egypt’s “failure to make progress on human rights and other issues.” In January, the US also gave Lebanon $72 million for police and army wages for the first time.

For Ibrahim, the deportation was a nightmare, he said. He spent two days held by what he called a “Syrian gang.” During that time, he was able to call relatives and gather enough money to pay a $4,000 bribe for his family to be released and allowed to cross back into Lebanon.

Now back in Tripoli, Ibrahim lives in constant fear of being deported again. “If they catch me, they’ll send me back to Syria,” he said. He is also now thousands of dollars in debt, after losing the money he paid for a place on the capsized boat on top of the bribe paid in Syria.

Now unable to pay rent, Ibrahim, his wife and son—now one year old—have moved in with his brother. Staying in Syria was impossible. But “in Lebanon, I don’t have anything left,” he said. “Living here is awful. There is so much racism. I can’t do anything, and no one is helping us.”

‘I want to see the world’

Back at the Beirut cafe, Salah scrolls through messages from his friend in Germany, Feras. “He said the journey was easy,” he says hopefully.

Salah has tracked down a trafficker who said he would take $6,000 for a trip on a boat from Morocco to Italy, and then to Germany. He has heard he could take a flight from Lebanon to Libya, and continue on foot through Algeria to reach Morocco for only around $1,000.

It is a long and treacherous journey, but also Salah’s best chance to leave, he says. “You’ll die here [in Lebanon], or will die on your way out. So, I’ll go out.”

“The first thing I do when I leave is to continue my education,” Salah says. “I’ll study and I’ll improve my English.” Pausing for a moment, he adds, “I’m still young. I want to see the world.”